Geography is a discipline defined by its conceptualization of, and attention to, space and place. Much like other modes of inquiry that have historically emerged from Euro-American perspectives, geography has mobilized reductive conceptualizations of space and place in material projects of dispossession and domination and in epistemological projects of delegitimization and hierarchy. In short, spatial knowledge, such as mapping and navigating the world, its peoples, and its resources, was and continues to be crucial to possessing, valuing, and rearranging space. Stemming from both internal challenges to geographical empiricism and the external pressure of the radical social movements of the late 1960s, “radical geography” emerged as a mode of thought around the world—an attempt to break with such modes of knowledge. Since then, the tradition of radical geography has become more introspectively self-critical, sometimes valorizing scholar-activism as an alternative mode of spatial practice. How can contemporary geographers both build on and diverge from the lineage of radical geography, not only to critique our discipline from within, but also to facilitate better and more widely “the selection and reselection of ancestors” (as Ruth Wilson Gilmore , drawing on Raymond Williams)? How are geographers fostering collective political projects that are conditioned by place-based Indigenous political struggles against capitalism and for alternative modes of living and surviving ecological crises? How might these questions open space for the broader consideration of a red natural history?

This essay suggests further transformation is possible and necessary: first, because of an incomplete reckoning with the fact that space and place are foundational concepts to Indigenous modes of inquiry, and second because self-criticism and scholar-activism alike tend to reinforce practices of individualistic inquiry, especially in the context of the neoliberalizing university. Both building on and diverging from the lineage of radical geography, this essay probes what the broader project of “Red Natural History” could mean for a spatially informed politics within, against, and beyond the discipline of geography.

The Call of Place

Place—one of geography’s central concepts—is also central to radical Indigenous thought and practice. Drawing on the work of Lakota scholar and activist Vine Deloria Jr., Yellowknives Dene theorist Glen Coulthard writes that for many Indigenous peoples “place is a way of knowing, experiencing, and relating with the world” (79). But one thing that differentiates this conception of place from that of many geographers is that “these ways of knowing often guide forms of resistance to power relations that threaten to erase or destroy our senses of place” (79). Kwakwaka’wakw geographer Sarah Hunt writes that in the past, “Indigenous geographies have remained peripheral to broader geographic theory” (29), seen by non-Natives as particular or regional subsets of knowledge rather than major contributions. Academic institutions favor piecemeal recognition, such as land acknowledgements, instead of broader transformation in commitments to decolonial anti-capitalism with all its messy responsibilities. Nonetheless, scholars engage in the latter by upending the responsibilities that universities and disciplines shirk. As geographers Soren C. Larsen and Jay T. Johnson argue, place is a more-than-human affair which thus has the potential to call to all who inhabit it to participate in political struggle (1). Place traverses institutions, species, disciplines, and subject positions. The authors describe how their respective settler and Indigenous ancestors ground their commitments to struggles that (to [146]) are “within and against,” “outside and beyond” universities (for example in a struggle over and for wetlands in Kansas owned by Baker University). The call of place is one potential meaning that could be ascribed to Deloria’s tantalizing description of “a new understanding of universal planetary history” (64).

Thus, while the concept of place is central to many geographers (especially those of us working after Doreen Massey), its resonance with Indigenous and other social struggles in defense of human and more-than-human flourishing is not automatic. A “red geography” could begin from the premise that any attention to place entails struggle. While we relate to place (and thus to each other) through historical positions shaped by (but not necessarily within) settler society and settler institutions (including universities), a red geography might ask us to establish relations to place that are incommensurate with settler society. Recognizing this mediation is crucial to building the counterpower that can break with that normative capitalist social order precisely by seizing and transforming institutions that would otherwise oppose us. Such struggles may still take place within universities—especially since they are still sites of labor and citymaking as well as knowledge production for the oil-soaked libertarian Right. How could the struggles of red geography be built within and beyond the discipline? Does naming it help us see its force?

Imperial Geography

The history of geography is deeply intertwined with European and North American empire. Alexander von Humboldt, perhaps our most famous progenitor, explored and mapped the species, landscapes, and occasionally peoples of North and South America in the service of the declining Spanish empire in the nineteenth century. In doing so, he created spatial knowledge that would condition and extend the functioning of imperial resource extraction across the two continents. Extending Humboldt’s legacy, the geographers Friedrich Ratzel, Halford Mackinder, and Isaiah Bowman each developed theories of place and power that sought to cement (respectively) the geopolitical prominence of Germany, England, and the United States in the early twentieth century. Their ideas of place and power assumed the prominence of European and Euro-American societies and militaries in a competitive, hierarchical, and ordered world system. Today, the tenor of their ideas is emergent once again in the role of (geo)spatial sciences in police surveillance, military action, and urban redevelopment, despite radical geographical criticism.

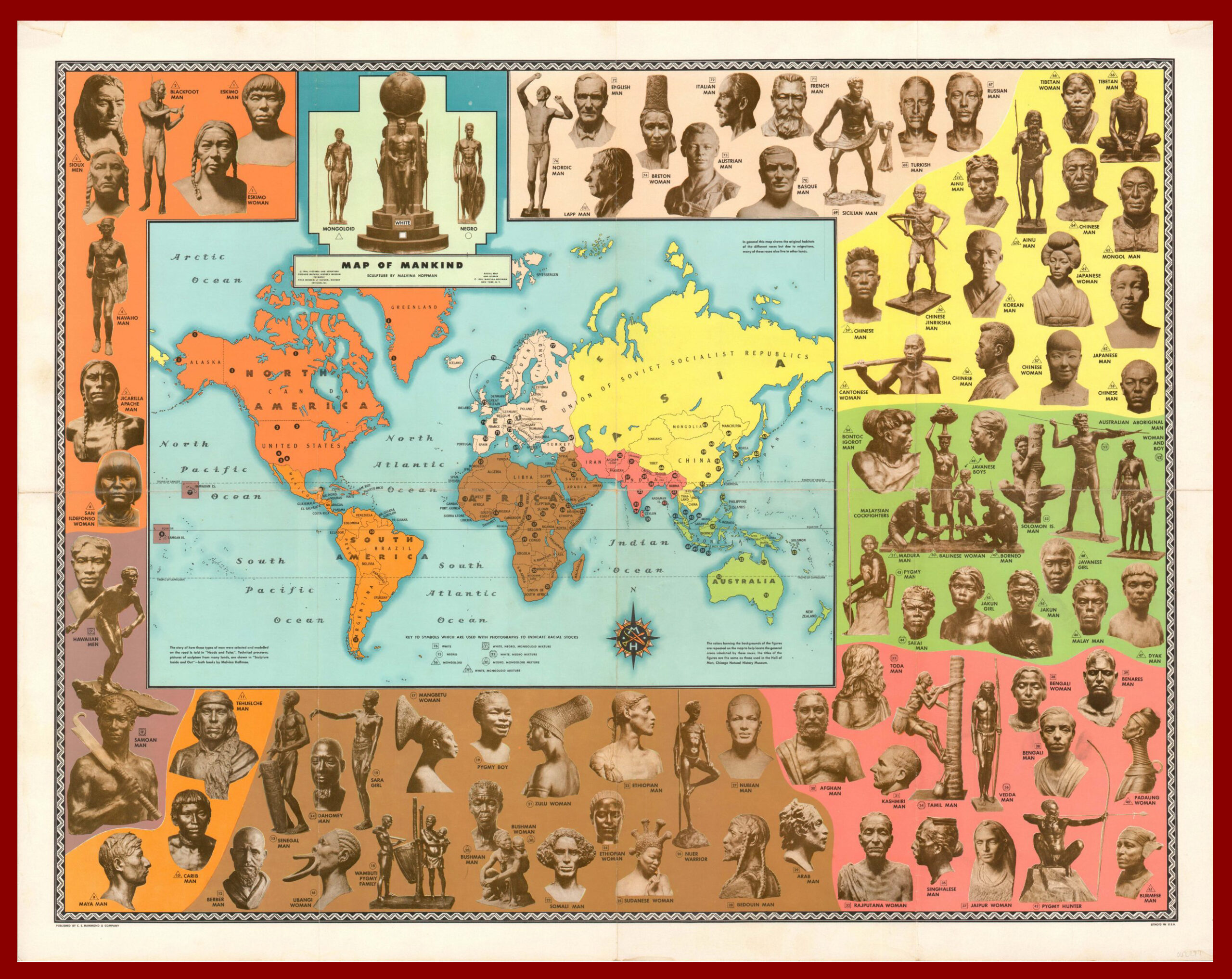

Mapping the world empirically naturalizes and hypostasizes the relationships among its elements. For example, maps and their spatial assumptions can (re)inscribe racial difference and hierarchy by representing people and places as fixed in different “developmental” stages (whether social or biological), serving everything from direct colonial rule to the imperialist financial policies of the World Bank and IMF. Such assumptions facilitate new avenues for capital accumulation, as “undeveloped” areas are seen to be either prime targets for resource and labor extraction, or sites for abandonment—proverbial or physical waste dumps.

From Self-Criticism to Collective Action

These origins haunt geography. They have led the discipline to frequent (self-)criticism, part of the inheritance of radical geographies, which have sought to challenge the supposed objectivity and innocence of geographical practice in the service of power. Conditioned by radical feminist, civil rights, ecological, and anti-war social movements, some geographers (many of them students) in the 1960s and 70s were spurred to re-evaluate their disciplinary methods and knowledges. Among their interventions included the founding of Antipode: A Radical Journal of Geography, which thrives to this day. Also founded at this time was the Socialist Geography Specialty Group (SGSG) of the Association of American Geographers (AAG) (now the Socialist and Critical Geography Specialty Group).

But the very emergence of radical geography was riven by internal tensions, many of which remain to this day. Is there any coherence to “radical” geography, or is it fractured and pluralistic? What is the relationship between the theoretical or practical knowledge that radical geography produces and the movements that condition it—especially given the unequal relationships amongst universities and the places they inhabit and/or influence around the world? And how “radical” is radical geography actually when it/we can uphold structures of patriarchal, racial, and imperial power in conferences and classrooms, and via key concepts?

In my admittedly limited experience in the last ten years, the subordination of scholar-activism to the university has frequently pressured graduate students, young scholars, and contingent faculty to frame these questions in an internally-limited manner. So long as we criticize each other (and our ancestors’ failings), we can still stake out a particular position, retain our innocence, and maybe earn a few citations. By encouraging self-criticism and individualizing our thought, the university works to prevent radical geographers from taking collective political stances, including towards decolonial action.

The academic job market and the contemporary university (through different but shared methods around the world) have produced variously hypercompetitive and austere labor conditions, valorizing only contributions that can be easily fitted into a CV. The need to publish in academic journals and speak at conferences encourages individual performance and interpersonal conflict over collective thought and action. Decolonial interventions end up paywalled in journals, featuring distantly political debates. Those involved in political movements end up so only as individuals (or connected to extra-academic movements), rejecting a collectivity as geographers. Though it might be reductive to explain it thus, to the extent that scholar-activism is allowed by the contemporary university, individuals are encouraged to find movements no one has yet studied, enter them somewhat instrumentally, and guard them jealously. Meanwhile, many university endowments have been built directly through Indigenous dispossession and remain dependent upon and thus beholden to the rates of growth of capitalist firms in which they are invested. Geospatial knowledge remains crucial to institutions of military, economic, and—as geographers recently have highlighted—policing and incarceration. All this prevents movements of geographers in solidarity with broader struggles to which we could be collectively committed.

Attempts to break out of this structure through mobilizing, for example, our professional societies can be very difficult. For example, in 2015 I became involved in a group advocating for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) of the state of Israel. A session we organized at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Association of Geographers brought short talks by Palestinian geographers, critical and radical geographers, and academics from other disciplines organizing around BDS. But despite a packed room and much excitement, the organization failed to materialize. Though there’s much to be said about the internal and external challenges of BDS in academia, at the time I remember feeling it was also particularly hard to organize a collective of geographers to do something as geographers when so many felt critical of the discipline and the university, while attached to movements elsewhere.

Place-Based Struggle, Within and Against the University

With that responsibility in mind, I want to open three further speculative boxes for conceiving of such place-based political struggle: political ecology, regional networks, and renewed socialist geographies.

I’ve always thought of political ecology as an interdisciplinary subfield of geography, anthropology, and environmental studies. So I was slightly taken aback when the artist and thinker Brian Holmes (along with friends) used the term political ecology to describe a repertoire of collective practices of inquiry into the world around us into which art (of all things) might intervene. Long based in Chicago, Holmes had gotten involved in place-based environmental justice struggles over petcoke waste sites, a byproduct of the tar sands pipelines I was studying and fighting against (not the same thing) in South Dakota. Along with several other Chicagoans, Holmes had started practicing political ecology as a “different, disalienating contact with the local territory.” In my interpretation it had become a method of seeing the world around us with an eye towards both the infrastructures of domination as well as its potential for common(ing) struggle. Rather than a political ecology written in journal articles, it became a kind of place-based cognitive mapping inquiry, which entails understanding the historical human and more-than-human forces capable of mobilizing for different futures. This is the kind of political ecology I realized I already practice with others in producing the knowledge for a toxic tour or in learning about urban natural gas infrastructure. It’s also about commitment to place that frequently involves cross-cutting struggle well outside academia, frequently uniting a motley group of working-class leftists, Indigenous peoples, Black and migrant workers, women, and queer folks, all committed to struggling where they are.

Such political ecology is ineluctably local, yet “local” feels like an insufficient word to describe its aspirations. Nonetheless, it differs slightly from regional struggle—which I see as increasingly important in a world where the jet-setting travel of academic conference circuits should be ending. Where I now work in the Virginia Piedmont region, I’ve been influenced by an emerging regional network of political ecologists brought together, in part, around understanding the relationship the tobacco industry has had with our cities and universities as one that Eli Meyerhoff and Gabriel Rosenberg describe as “Piedmont .” Regions are also the focus of critical non-academic political writing, such as the “POC-led, women-run” Scalawag magazine here in the US South, from which we could also well learn how to “reimagine the roots and futures of the place we call home.” Networking some of the scales of struggle described above, the regional projects constellate their power to perhaps challenge the twenty-first-century regional power blocs constituted by coal, tobacco, health care, finance, and higher education, which tend to prolong the afterlives of settler colonialism and slavery. To me, this practice inherits analysis and political commitment from geographer Clyde Woods, whose focus on regional struggle is sometimes forgotten. Regional struggle entails the connectivity of place, the circulation of modes of knowledge, and strategies of counterpower that might reshape the political landscape.

Though involved in place-based struggle, geographers will still communicate and advocate through disciplinary interest groups. Over the past few years, the aforementioned Socialist and Critical Geography Specialty Group (SCGSG) has been the site of debates over the vision and politics of radical geography, especially concerning necessary intersections with feminist and anti-colonial struggles within and beyond academia. SCGSG members are certainly politically diverse, yet are still capable of gathering under a name and articulating shared commitments—such as to defending and transforming higher education practice in the context of induced austerity. But if radical geography is to be (re)committed to the kinds of shared, decolonial, anti-capitalist place-based struggle described above, how would the commitments of this group be reconceived? And what connections are to be forged with the Indigenous Peoples Specialty Group and Black Geographies Specialty Group, with socialist organizations, and with international socialist struggle? These are speculative but crucial questions, which might form conditions that would enable us to act collectively as geographers.

Collectives have to be forged. This is doubly true when situations attempt to cleave us from each other and our relations so that we operate as individuals. Many other practices of social struggle might, as Eve Tuck frequently suggests, not be deserved to be counted and catalogued in the university. Drawing on Deloria’s writings with Muscogee scholar Daniel Wildcat Jr., , then the contemporary forms of academic knowledge production recognized by conventional university structures will be insufficient. Nonetheless, this does not mean that we ought to pack it up and accept the apocalypse. A red geography could be seen in pathways for combatting and overcoming the ressentiment of self-criticism and individualization in our practice, finding its form in place-based dis-alienating practices that seek to coordinate thought and action.

Kai Bosworth is a geographer and assistant professor of international studies in the School of World Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University. He is the author of Pipeline Populism: Grassroots Environmentalism in the 21st Century.