Kai Bosworth is geographer at Virginia Commonwealth University and a 2023-25 Red Natural History Fellow. In this edited conversation with The NHM’s Steve Lyons, Bosworth discusses the key divisions forming under the banner of “environmentalism” today, challenging us to rethink and recompose the “we” of our collective struggles against extractive capitalism.

Steve Lyons (SL) What brought you to your current work as a researcher and activist working on fossil fuel infrastructure in the US?

Kai Bosworth (KB) I’m interested in understanding opposition to oil pipelines in the United States, in part because I am also opposed to oil pipelines in the United States. Since getting involved in the youth climate movement in the early 2000, I’ve spent almost 20 years trying to understand how to produce radical and transformative climate justice here in North America. My interest in oil pipelines also stems from having grown up in western South Dakota and attempting to understand the history of resource extraction in that region, as well as how that history was tied to colonialism and to the outright colonial theft and poisoning of much of the Black Hills where I grew up. I have been trying to think about how, over the last century, movements in this region have tried to create a radical response to these kinds of rapacious effects.

Out of this context, my academic and political work tries to help us see environmentalism as an umbrella for a variety of political positions, not all of them acting in concert or with the same goals or strategies in mind. In my academic work, I try to single out and think through one environmentalist tendency, which I think of as “populist environmentalism.” Most basically, populist environmentalism takes appealing to “the people” as a strategy for producing climate action. But in the process, it tends to shy away from radical or transformative demands that may not appeal to the broad imaginary of democratic politics in the United States. My work unpacks the difference between populist environmentalism and the radical and transformative leadership of Native Nations in opposing pipelines—a distinction that allows us to see why the former tends to reproduce forms of whiteness and fealty to liberalism, both factors that hamper its capacity to build alliances with more radical tendencies within the movement, which see environmental action and action against oil infrastructure as only one part of a broader movement for decolonization or a reclamation of sovereignty.

Right now, I’m continuing to think about movements against oil and gas infrastructure, including pipelines, but also active and abandoned oil wells, refineries, and the sorts of waste that are also associated with oil and gas production. This current work is examining how a variety of movements and organizations across North America are trying to highlight the impacts of oil and gas infrastructure on subsurface spaces.

Oil wells, pipelines, the injection of wastewater from hydrofracking and new forms of carbon dioxide sequestration are disturbing underground aquifers, caves, salt domes, and the geologic stability of the land underneath our feet. But in order to demonstrate this, activist groups have to use scientific data and their imaginations to try to make these subsurface spaces worthy of our attention, because most of the time we don’t really experience or think about what’s under the ground on which we stand. The sorts of groups I’m engaging with now are facing a classical political problem: how to represent and thus extend the meaning of what they cherish, and what they oppose. In this way, they’re trying to demonstrate why we have to understand and care for both the subsurface and the surface world.

Mapping Imperial Geography

SL I’ve been familiar with your work for a long time, but as I was rereading some of your work, I started to narrow in on two central problems that you’ve been dealing with. The first, which you engage directly in your contribution to our recent Red Natural History essay series, is the problem of liberating the discipline of geography from its imperialist baggage—of rethinking the discipline’s priors and priorities so it can effectively participate in anti-capitalist, anti-colonial movements. And the second, which I think is related, is the problem of building a revolutionary collective within the current conjuncture—where what you call “pipeline populism” has come to substitute for the durable forms of collectivity we need. In both senses, you’re helping us think through the challenges of finding alignment between constituencies and projects that are not necessarily on the same side, but could be.

I thought we’d start with the first problem. What is the imperialist tradition of geography? How did it evolve into the twentieth century? And what does this historic connection between geography and imperialist expansion, militarism, and imperialist rule teach us about how practices of research can be part of a transformative political project—in this case, the political project of imperialism?

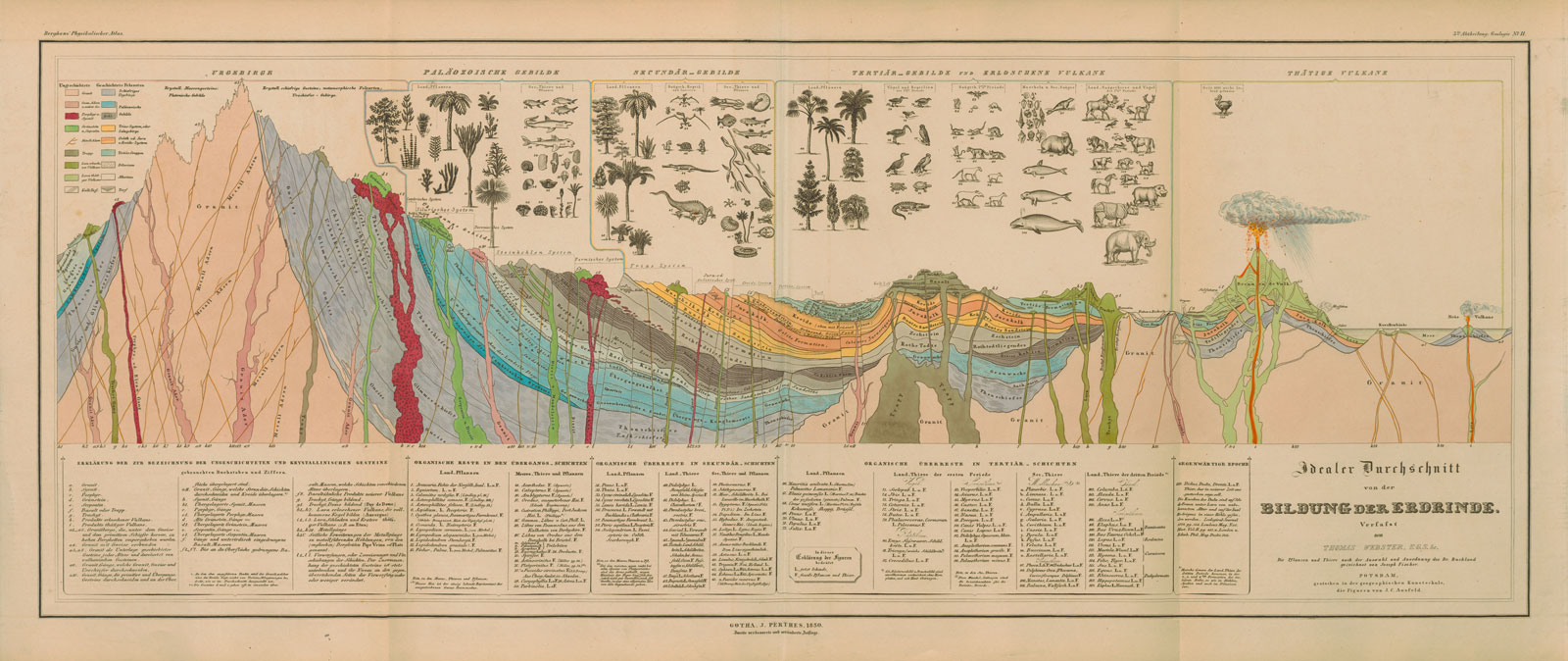

KB Like a lot of Western modes of knowledge, geography has a long and intimate history with the imperial project. Paramount to the project of building empires was the process of knowing lands from a distance, understanding what peoples, resources and non-human animals populated these lands, and understanding how to move those people or resources in ways that maximize profits and produce value for the imperial core. As it emerged as a discipline, geography was crucial to this project, especially in North and South America, as well as later and in different ways in Africa, South Asia, Southeast Asia.

In the Americas, we can think about the history of the discipline through a figure like Alexander von Humboldt, who traveled all through the Americas to engage in early mapping projects, before bringing maps back to the imperial core to develop the methods of communicating spatial knowledge about the sorts of resources available to exploit in colonies, why and how wars could be fought, and so on. Obviously this form of knowledge collection is relatively easy to critique. And yet, as geography transformed into the twentieth century, its disciplinary knowledge continued to be used to advance new forms of imperial exploitation as well.

Out of this history, a whole theory in geography emerged that was consistent with nineteenth century racial science, which sought to categorize people based on their climate, and from that, to derive a moral understanding of their character, their value, and their intellectual type, and then to arrange it in a hierarchy, where the Europeans were at the top, and then below them, a variety of other peoples who were allegedly shaped by their climate to be better workers than thinkers, or who were believed to have certain kinds of feeble personalities. Populations deemed less civilized were thus also deemed incompetent to govern themselves, which meant they needed to be shepherded by the imperial powers. The racial and racist hierarchies of what we call “environmental determinism” eventually came to shape these justifications in rather direct ways. They were extended in the German Nazi understanding of the world, and in the wake of the disaster of the Holocaust during World War Two, as well as the influence of decolonization movements around the world, these forms of outright racism in geography were challenged more heavily.

This internal reckoning opened up a space within the discipline for a more radical reevaluation of how we should think about space, place, and people. By putting capital and capital accumulation and imperialism onto the map, geographers started to take those tools that were originally developed in and for imperial power and to use them toward another end. The idea was that by mapping the concentrations of power, wealth, and capital, geographers might understand how these structures could be transformed, fought against, and so on. The tradition of “radical geography” that began in the 1960s and 70s reshaped our discipline in a lot of important ways, not only by challenging imperialism and capital accumulation, but also by opening up space to cross-pollinate feminist, queer, anti-racist and other forms of spatial knowledge.

At the same time, geography continues to be shaped by our history. This has sometimes created a kind of excessive self-criticism, where it can seem as if geography can only ever be an inheritor of its imperial history. Against this tendency, I think about geography as a discipline that has been split at its foundations. On the one hand, we have these imperial projects, but on the other hand, we have long histories of radical understandings of space and place, alternate concepts that might help us challenge the imperial mode of geography and its particular concepts of space and place. If we wanted to not only describe the imperial project but also intervene against it, we could draw on the knowledge of Red Power and many other past movements, for example, which developed their own modes of spatial knowledge in order to expose strategic weak points in the financial system, the arms industry, the resource extraction and transportation industries.

Thinking the “Unthought”

SL Thinking about the difference between this critical mapping of capitalist relations, and, quoting Glen Coulthard, the project of drawing on this place-based knowledge to “guide forms of resistance to power relations that threaten to erase or destroy our senses of place,” it seems important to delve into the uneasy relationship between the kinds of scholarly or analytical modes that we use in our research and the forms of resistance we seek to participate in or contribute to. What are the challenges of conjoining research and activism? What does it look like to be a good scholar and a good comrade at the same time? Is it about asking the right questions? Is it about research ethics, where you pour your research and time into, or who you give your findings to?

KB The demands of any given social movement trying to achieve change are oftentimes a little bit different than the demands of academic research, which for me involves zooming out and reflecting on the broader landscapes in which a given struggle is situated. When we were trying to stop the construction of the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines in the upper Midwest, we had a very practical problem to solve. We had to try to understand where the pipeline would actually get built. This knowledge was not available to us because it was deemed a security risk, because pipeline firms often invoke the threat that terrorists might blow up pipelines if their precise routes are made public. Within this context, we had the very pragmatic task of actually mapping out where the pipeline was going to be with a moderate degree of detail so that we could try to build a political coalition of people on whose land the pipeline crossed. Those could be potential choke points, where the oil infrastructure itself could be challenged.

What makes a good political thinker is the ability to participate in that kind of pragmatic research while also situating its importance within a broader tapestry of changes that are taking place broadly within the capitalist political economy and the ecological system. Sometimes what that means is trying to participate in movements with an eye towards understanding what their unthought is: what is the thing that isn’t necessarily being considered? Is there a way that you can articulate what that unthought is, not necessarily to intervene in this particular moment, but in order to help prepare for the next movement or the next cycle in the cycle of struggles? That was particularly important for me in the movement against the pipelines. And it remains a problem for our movements to think through insofar as our opponents are constantly adapting to what we are doing as well. Our opponents are trying to anticipate and figure out what the unthought of our movements are and try to stave it off. We have to be constantly adapting and updating our knowledge because they are as well. Beyond our ability to have time to wash dishes on the blockade and other sort of pragmatic things, political thinkers can offer movements a capacity to traffic between the day-to-day pragmatic needs of the movement and its broader context, where we can begin to see and understand what it is taking for granted. Of course, none of this is to say that I don’t have an “unthought” of my own!

Dividing the Environmentalist “We”

SL Much of your research explores the unstable, contingent “alliances” that form in the midst of pipeline struggles. You wrote an important book on this phenomenon, where I think you offer an important lesson about the risks of banking on immediate material interests and/or what we’re against as a basis for political struggle. Can you expand on what you think the “unthought” of populist environmentalism is? Where did it come from, where do we see it today, and what does it produce in terms of a politics of “strategic alliance”? What did your work on the Dakota Access Pipeline struggle teach you about the limits of the populist frame and the demand for a more granular understanding of these alignments?

KB Populist environmentalism is a way of understanding one particular tendency within the broader ideological field of environmental politics. If you think about environmentalism as a field of competing ideologies, on one side of the spectrum, we have the traditional Big Green organizations that are composed of elite individuals and boards and funders and the like, and thus take on strategies and tactics in alignment with elite interests. For them, environmentalism is a project of protection—conservation, protection fences, borders and so on. On the other side, we have the varieties of green anarchism and eco-socialism, which seek to confront what they see as the root causes of environmental damage in our social, economic, and political systems. And of course, we can think of all kinds of tendencies in between. Populist environmentalism, in my mind, is one way of naming a reaction against both the elite Big Greens and the kind of technocratic environmentalism which sees the management of environmental damage as a job for politicians, business leaders and these elite Big Green organizations. In both of these visions of environmental politics, regular people are nowhere to be seen.

In the 2010s, governments and elite interests were proposing all sorts of supposedly “pragmatic” solutions to the urgent global problem of climate and ecological crisis, but at the same time, the United States continued producing more and more oil and gas, becoming the biggest oil and gas producer in the world. Populist environmentalism was one critical answer to the ways that elites seemed to influence our political process—both the way that they had consolidated power through the oil and gas industry as well as within the Big Green organizations.

Populist environmentalism’s story about the world is seductive to me in a lot of ways. And in places like South Dakota, where there isn’t a lot of transformative political radicalism, populism has been an important way of taking the grievances of regular people and elevating them. I don’t begrudge this form of politics or its aspirations by any stretch of the imagination. Yet, at the same time, what my research showed was that forms of populism in the movement against the pipelines also became hamstrung by its simplistic narrative about who was responsible for the crisis and how it should have been addressed. If you understand the problem of oil and gas infrastructure as the result of a small number of oil and gas firms that have only recently captured or corrupted the American political system, then some sort of restoration of democracy is imaginable. And if you understand “We the people” as the authors of our political existence, you can leave out or obscure some of the real problems that American democracy has enacted at the expense of Indigenous Nations, which makes it difficult to think about what repair may be necessary.

Rather than posit the people as an abstract entity that will save us if we only get rid of the corrupt politicians, I think it is necessary to compose the kinds of alignments and organizations that can produce an enduring political struggle capable of revising our relationship to politics and the environment. And this alternative requires a lot more work and takes a lot more time than the populist environmentalists hoped would be true. But it can also produce much stronger and less parochial relationships among Indigenous activists, the inchoate parts of the left, and in places as far flung as rural South Dakota, farmers and ranchers who are not just facing incursions on their private property, but are now subject to the whims of a global commodities market. These conditions produce grievances as well as feelings of despair, hopelessness, anger and indignation. But we have to tell different stories about our social relationships with others in order to begin to organize and build durable and lasting institutions that are going to be capable of growing at the same time as they confront a radically transformed world.

SL You’ve described the book as a “something of a tragic analysis,” sharing with Mike Davis an interest in understanding the “lack of mass socialist participation in a coherent, avowedly anti-colonial movement in the US.” What do you think has hampered that socialist participation within the Indigenous land and water struggles of the past decade? And where do you see, if not “hope,” possible movement in the right direction?

KB There are a lot of different ways that we could think about the missed connections between Indigenous radical movements and movements of working class leftists and organizations across North America and across the world. Perhaps one of the things that has contributed to that missed connection is an inability on the part of non-Indigenous workers or settlers to understand the ways in which their social position was being used by the state and capital as a wedge against Indigenous nations. When you are part of a class that is itself being exploited, it can be difficult to understand that your exploitation is rendering others even more dispossessed or more exploited at the same time. But alignments can and could grow around an injunction against exploitation and dispossession at the same time—against the ravaging of ecologies, environments and landscapes in the process of capital accumulation, a process that has also produced ruin for proletarian people around the world. We need to be constantly thinking about how we can listen and learn from the stories and histories of others who might be substantially different than us.

Capitalism is itself productive of competition, and that means that it has fragments and cracks within it, both at the level of competitive firms and the way that that these firms struggle over the political sphere, over nation state governments, between governments around the world, in global institutions, whether the UN, the IMF, the World Bank, World Health Organization, global Green groups and the like. In order to respond to ongoing crises and instability, they need to act in concert. And so do we.

Part of what this entails is narrating the crises that we face and understanding them as part of not just their individual landscapes, but part of this world system that is predicated on exploitation and dispossession. I found this recent statement that the Colombian president Gustavo Petro made about the ongoing war against Gaza conducted by the State of Israel and its allies to be particularly interesting in this regard. Petro is trying to think about how this immense, concerted violence against a confined people is what the climate crisis is becoming for the world at large. He writes that “the political right in the West sees the solution to the climate crisis as a ‘final solution’,” a genocidal action of the “rich and Aryan peoples of the West and our Latin American oligarchies who do not see another world where we live, other than that of the malls of Florida or Madrid.” He continues:

“We are all going to barbarism if we do not change power. The life of humanity, and especially of the people of the South, depends on the ways in which humanity chooses a path to overcome the climate crisis produced by the wealth of the North. Gaza is just the first experiment in considering all of us disposable.”

In part, this is a negative diagnosis of what we are up against. But it is also an attempt to produce a common sense of what we are all facing. When we understand our disposability for capital accumulation, for the preservation of this system of wealth and extraction, we can see struggles that might otherwise appear as drastically different to be part of a shared movement for a world that would actually make us indisposable.

Drawing the Red Line

SL Petro’s statement is exposing this dynamic that has, throughout the history of capitalism, played out at different levels and scales, and which is in a sense expanding to the world scale under climate change. We’re at a good place in this conversation to shift into the question of “red natural history,” which as The Natural History Museum proposes, is about the stories, narratives and ways of doing research that allow us to see the world that capitalism needs to consume, a world that is larger and more powerful than the capitalist world—but which is invisible from a capitalist point of view.

To return to where we started, if we see natural history as a constellation of practices and modes of inquiry that are never far from the actual praxis of transforming lifeways and landscapes, we can immediately start to see how natural history could either aid and abet capitalism or work towards its abolition. When we started the “Red Natural History” project, our hypothesis was that while it’s easy to see how the imperialist mode of natural history has a material force in the world, it’s much harder to see how practices of natural history that resist imperialism do too. For us, “red natural history” offered a name for this countervailing tradition of natural history—an internally diverse tradition, composed of practices that stand in the way of capitalism’s unceasing need to enclose, extract, exploit, and dispose.

You’ve been involved with The Natural History Museum for many years and have been thinking with us about red natural history for a while now. How do you understand this term? If, following Raymond Williams, we define tradition as “the selection and reselection of ancestors,” how might you describe the ancestral line of red natural history? What ought red natural history fight for? And where might we see its outlines in the world today?

KB At first blush, “red natural history” marks a division. On one side, you have traditional natural history–let’s call it “gray” natural history, a tradition of natural history made up of processes and institutions that have driven all of our climate and ecological crises, as well as the kinds of social violence and misery faced by working people around the world. On the other side, you have movements of Indigenous Nations, workers, socialists, and communists, who have spent centuries fighting to repair and transform the world so that present and future generations of people and non-human species can flourish. We can see this divide within different social groups, classes, and institutions, and certainly within disciplines like geography, geology, environmental science and natural history.

Red natural history helps us challenge two seemingly distinct reactions to the climate crisis that are particularly unhelpful. First, red natural history pushes against the technological or market optimists, who would suggest that there is no divide, that we’re all in it together, that politics is too disruptive, and that we should simply be neutral. I think that this position is clearly bankrupt. We know that capitalist firms, the oil and gas industry chief among them, are doing anything and everything in their power to prevent any sort of social and environmental action. We’re not all in this together. We’re on different sides. At the same time, red natural history also pushes against the melancholic or nihilistic position, which imagines that the damage is already done. Everything turned bad hundreds of years ago, with the beginning of capitalism or colonization or Western science, or even with the invention of agriculture, and thus there’s nothing that we can do, salvage or fight for.

In contrast to these positions, which are two sides of the same coin, red natural history invigorates us by showing the degree of organization and commitment that our ancestors have had in fighting against slavery, exploitation and colonization. Some of these ancestors have worked within academic disciplines and within universities, but others have worked beyond and against these institutions. And these ancestors didn’t give up when things were bad or when the odds were stacked against them. If they didn’t give up, why would we? The point is to begin to resuscitate the courage, will, organizational structures, and maybe even the humor of those who struggled before us, as well as the forms of knowledge that have been accumulated in and passed down to us from these long-term struggles.

We can learn, for example, from the anti-colonial struggles of the mid-20th century, both their successes in producing forms of sovereignty and independence as well as their challenges in facing new forms of neocolonialism and exploitation. In learning from their struggles, we can understand that there’s no “flip of the switch” that will instantly solve all our problems. And indeed, we shouldn’t expect that our struggles will be won overnight. We inherit the struggles of our ancestors and we will be passing down these struggles to people after us, who will learn from our mistakes. By giving us an inventory of the histories and ongoing struggles for human and non-human flourishing, red natural history can provide a lens for us to see the possibility for flourishing elsewhere and in each other, so that we can continue to grow and popularize the desire and necessity for a radical transformation of our politics and economy.

Kai Bosworth is a geographer and assistant professor of international studies in the School of World Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University. He is the author of Pipeline Populism: Grassroots Environmentalism in the 21st Century. He is a 2023-25 Red Natural History Fellow.

Kai Bosworth is a geographer and assistant professor of international studies in the School of World Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University. He is the author of Pipeline Populism: Grassroots Environmentalism in the 21st Century. He is a 2023-25 Red Natural History Fellow.