Dina Gilio-Whitaker is an Okanagan descendant of the Colville Confederated Tribes in Washington state. Born and raised in Los Angeles, she now teaches American Indian Studies at California State University, San Marcos. As a writer, educator, and one of The Natural History Museum’s inaugural Red Natural History Fellows, she is developing a Native perspective on environmentalism and environmental justice, responding not only to the specific experience of dispossession, genocide, and assimilation experienced by Native Nations in the so-called United States, but also to the current reality of peoples who continue to be subjugated by the settler state. In this edited conversation with The Natural History Museum’s Steve Lyons, Gilio-Whitaker explores the challenge of mapping the dominant understanding of “environmental justice” onto the experiences of Native Nations, offering a clear-eyed vision for an Indigenized environmental justice, which has traditional knowledge and Tribal sovereignty at its heart.

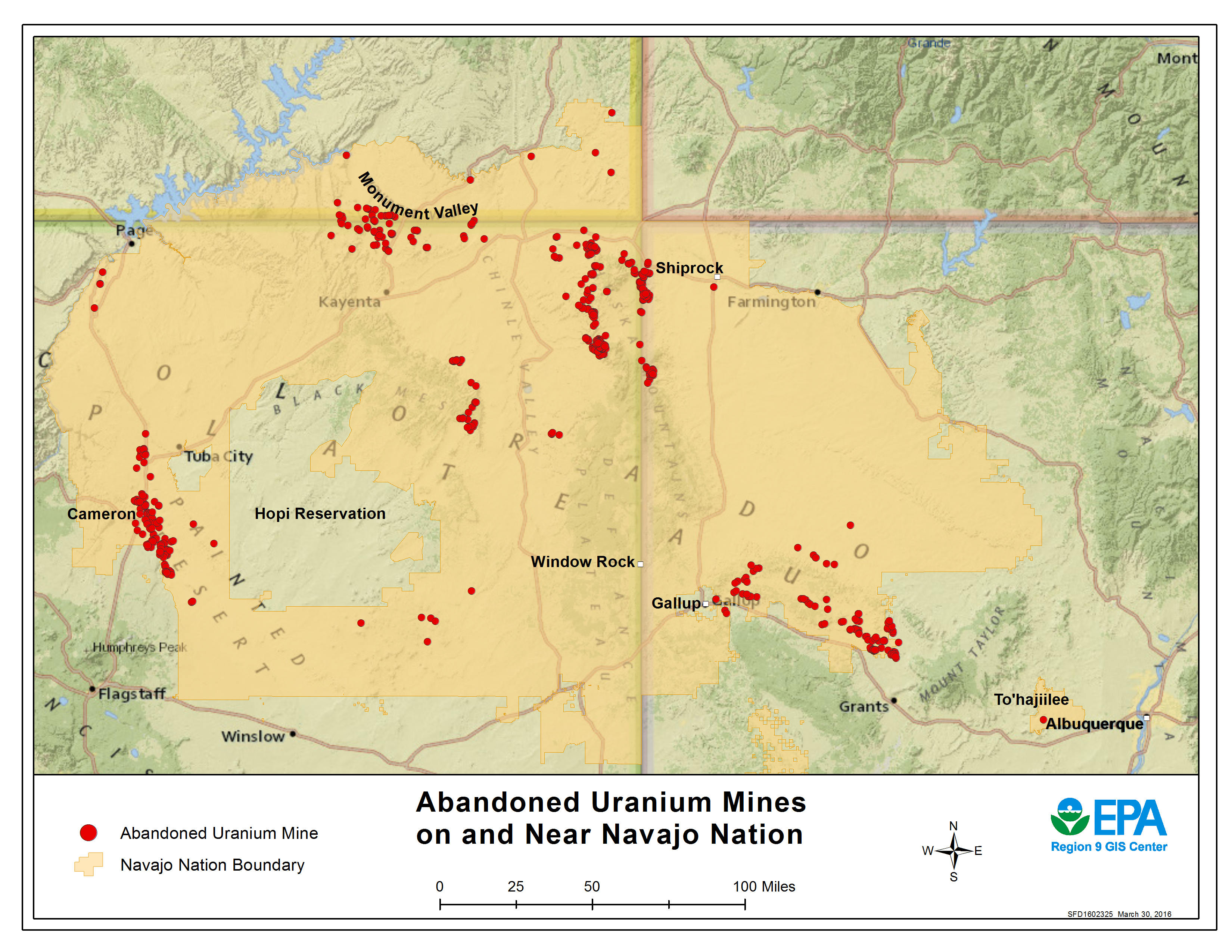

Steve Lyons (SL) In your most recent book, As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice from Colonization to Standing Rock, you note that “of the United States’ 1,322 Superfund sites, 532 of them were located on Indian lands — an astoundingly disproportionate figure considering how little of the US land base is Indian trust land.” Could we start by talking about how this came to be?

Dina Gilio-Whitaker This is a pretty astounding figure, considering that less than 5% of land in the U.S. remains to be tribally held. So how do we understand that this disproportionate amount of land of Superfund sites is on tribal lands? I think the best answer to that question is that in a settler colonial system like the US, Native lands and Native people are considered disposable. Settler-colonialism dehumanizes Indigenous populations in order to justify the systematic dispossession of Native land.

Within this dehumanizing structure, Native people and Native lands enter a process that Traci Brynne Voyles describes as “wastelanding.” In Wastelanding, Voyles helps us understand how, especially in the Southwest, Native reservation lands became reservation lands because they were considered wastelands — places that settler populations did not consider valuable. But after the reservation system was established, the whole nuclear industry began, and geologists discovered that materials like uranium were abundant in these lands that had already been written off, kickstarting another wave of extraction, this time on or near the reservations.

We’re now in a new “clean energy” era, where lithium is poised to become the new uranium, and lithium mining is every bit as extractive and contaminating as uranium mining. If this cycle of dispossession continues, we’ll have the same issues all over again.

SL In addition to this process of despoiling, you chronicle ways in which colonizers and settlers re-engineered the landscape to starve Indigenous communities into submission, a process of “environmental deprivation” that fundamentally transformed the environments in which people are capable of sustaining their cultural traditions and ways of life. In the NHM’s vocabulary, we describe this as a process of “making natural history.” How has settler colonialism left its mark on the natural history of the planet — if we understand natural history, broadly, as the history of the environments that sustain collective life? And what incommensurate practices, modes of life, and ways of understanding the environment did this process extinguish?

DGW If we start by thinking about the US conservation movement, which arguably began with the founding of the National Parks system in the late-nineteenth century, we can see how the effort to preserve and conserve “wilderness” could be part of a process of settler-colonial domination. In the dominant conservationist tradition, the idea of wilderness is conceived in a very Eurocentric way, which in the nineteenth century was based on the settler-colonial fantasy that the natural world was a place without people that needed to be protected from people. Of course, this mythology of an unpeopled landscape perpetuated European ideas that justified the invasion of Native lands as if they were uninhabited. There were millions of people on the land when Europeans arrived in the Americas, but from the settler-colonial vantage point, these original inhabitants were not considered people with pre-existing rights to land.

The landscapes the Europeans encountered as they made their way across the continent looked to them like “pristine” environments, untouched by human hands. This was a misconception, of course. Indigenous peoples had, in fact, been managing all kinds of ecosystems, including forests and grassy plains. Across this continent, Native peoples were maintaining or altering landscapes in ways that benefited themselves, but also benefited the environment. But when the Europeans invaded these landscapes and moved the Indigenous populations off the lands they stewarded, they also removed the longstanding practices and processes that Native people were using to maintain them, from cultural burning to harvesting particular crops in ways that would nourish the soil and perpetuate the greater growth of that food source. The same was true for the harvesting of salmon in the Columbia plateau. The salmon were abundant, but the Native people who harvested them did so in a way that ensured that abundance.

As they made their way across the continent, the Europeans remade the land in a very Eurocentric way—not by managing the land in ways that ensured the abundance of natural resources, but in ways that exploited and used them up.

We could look at the building of dams, which was a significant settler-colonial project into the twentieth century. Settler states built dams in order to facilitate water storage, which was part of a broader project of facilitating large-scale agriculture. But when you build dams and create these water storage systems, you also create lakes where they didn’t previously exist. You alter ecosystems in multiple ways: not only by pushing Native people off their traditional lands and into places that have less food resources, but also by making it impossible for these ecosystems to regenerate themselves in the ways they were used to.

Remaking the landscape in a Eurocentric way always brings life to settler populations, but brings death to Indigenous populations. This is part of the cycle of ecocide and genocide we call settler-colonialism.

SL In As Long as Grass Grows, you argue that the way we’ve come to understand “environmental justice” in the US doesn’t map onto the environmental injustices faced by Indigenous peoples. Can you outline the problem you see with the dominant conception of “environmental justice” and what it looks like to center environmental justice on the experiences of Indigenous Nations?

DGW The concept of “environmental justice” was not conceived until the early 1980s, growing out of the civil rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s. We all know the civil rights movement did not solve all the problems. Racism did not magically go away, and it took many forms. Looking at Black communities in the Deep South in the ’80s, people began to see a new articulation of racism that had this very particular environmental quality to it.

In this context, communities were coming to understand that they were being unfairly targeted as sites for toxic waste dumps and other harmful infrastructure because they were Black, poor and powerless. They called this environmental racism. And sure enough, the concept stuck, because not only was it happening in Black communities in the South, but also in other communities of color. For example, Chicano and migrant farmworker communities in California were working with pesticides that turned out to cause disproportionate incidence of health problems.

With numerous community-based studies proving this dynamic, people came to define environmental injustice and environmental racism as the disproportionate risk of negative health impacts faced by ethnic minority communities. This is a very specific definition. While it is irrefutable that racism plays a key role in the distribution of risk, the concept does not help us understand other historical processes that are specific to the experiences of Indigenous peoples: the experience of invasion, land theft, and environmental deprivation, which were intended to eliminate them .

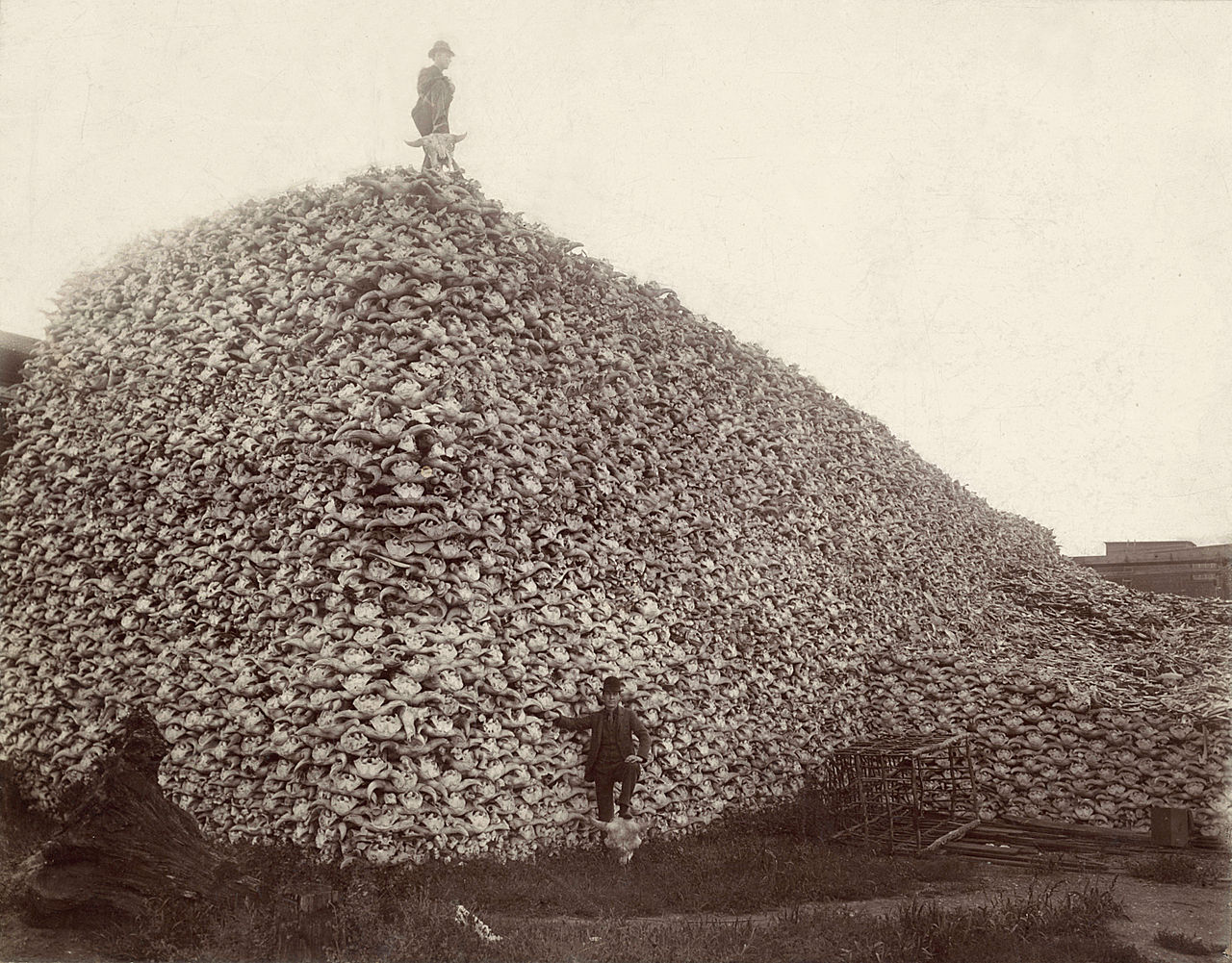

We can look at intentional starvation as an example of environmental injustice that environmental racism does not help to explain. Take the case of the extermination of the buffalo, which was a means by which the settler state could dominate Native people, literally by starving them into submission. This was a form of environmental deprivation that was not primarily stemming from a process of racialization and racism that, by consequence, exposed Native people to risk and harm. It stemmed from a deliberate genocidal project waged by the United States, which targeted the environmental health of Native populations in order to take their land.

If we understand settler colonialism as a process of dispossessing Native people in order to take land, it offers a much larger framework for understanding injustice than either racism or the exposure to risk and harm. And it is a very specific kind of injustice that Native people experience, which cannot be mapped onto the experiences of other ethnic minority populations. This is why I argue that we have to understand environmental justice for Native people not through a lens of environmental racism, but through a lens that centered on these colonial processes that are fundamentally about taking land and replacing Indigenous populations with settler populations.

We have to think beyond racialization when we think about the process of settler colonialism. It’s not just about racial discrimination. It’s always about the land. Environmental injustice for Native people is inseparable from the taking of land.

SL If environmental justice for Native peoples needs to center the question of land, what does this look like in practice? What does an “Indigenized” environmental justice look like?

DGW We have to begin by recognizing that Indigenous people have lived on the continent for untold generations in ways that were sustainable. They understood the limits of ecosystems. I think that we need to learn from them. We have built societies based on unchecked technological development, and very short term thinking. Indigenous Nations lived sustainably for generations because they thought long term. Yes, they altered their environments. But when they did, they asked how their interventions would impact the environment for the next seven generations. Virtually all Indigenous societies in North America thought in this way. They had different ways of characterizing it, but they were always thinking into the future. If we are to survive, I think this is something that modern society needs to learn.

This is the question for me: can we live in a technologically intensive society in a way that’s sustainable? And I don’t think this question is being adequately addressed.

SL As I was reading your work, I was struck by a consistent emphasis on the power of knowledge, pedagogy, and learning in producing conditions for transformative social change. Can you describe your theory of change — how we get from a colonized capitalist world to a better world?

DGW For me, Indigenous knowledge is important because it centers the core values of kinship and reciprocity. When you center these values, you live with respect and responsibility on the land. These are not the values that Eurocentric societies are grounded in. By contrast, Eurocentric societies are based on the endless exploitation of the natural world, and it doesn’t take a PhD to understand that this is not sustainable. But it’s not like the values of long term thinking and relational thinking are only limited to Indigenous populations. Every human society has some kind of understanding of kinship and reciprocity. The question is how can we take those kinds of values and center them in our modern ways of living?

SL In our past conversations, you’ve raised the ways in which Indigenous ways of knowing, traditions, and identities have been appropriated by white settlers — like in the Back to the Land movement — underscoring what these appropriations got wrong. But you have also been clear that settlers have a lot to learn from Indigenous people, traditions, and relations to the land and water. Can you elaborate on this problem of Indigenous identity: how might we parse the distinction between an Indigenous practice and an appropriative practice? Or, to look at it from another angle, when Indigenous practices are appropriated in problematic ways, what central features, ideas, agencies or values are being stripped from them? And where do you see a path beyond the violent assimilation of Indigenous identities into the settler-capitalist frame? Is it possible for settlers to learn from Indigenous practices without recapitulating the Back to the Land problem?

DGW When I talk about the problem of cultural appropriation with the Back to the Land movement and in second-wave environmentalism, I always say that those hippie folks were well-meaning. For a long time there was a lot of stigma about being Native. Native people were constructed as inferior, uncivilized and primitive. But with the growing anxiety about what industrialization and rampant extraction were doing to the environment—with the contamination of rivers like the Cuyahoga River, which famously caught on fire many times, and with the Santa Barbara oil spill in 1969—young people began to show some respect to Indian country, recognizing that Native people had lived in harmony with the land since time immemorial, and seeing in Indian country an example for settler society to follow.

At the same time that the counterculture adopted a new respect for Native people, they showed this respect in a way that was suffused with what I call “settler supremacy”: an entitlement to the land that lays at the foundation of settler society. One way that settler supremacy manifested in the hippy counterculture was in their sense of entitlement to taking on cultures and identities that were not their own. You see this emulation in the adoption of a Native aesthetic: growing long hair and wearing headbands, fringed leather, beadwork and feathers. There is a clear appropriation of culture going on. Hippies were going to the reservations to learn from the medicine people, which then led to a growing rise of fake identities — people pretending to be medicine men and Indians themselves.

Today, as new environmental problems are ramping up, there is a renewed recognition that Indigenous knowledge might be really important for how we, as societies, will negotiate our way into the future. People now understand that traditional Indigenous knowledge can offer a framework for asking how we can better manage the lands, how we can negotiate our way through troubled times. While there is always a risk of misappropriation, as there was in the 1960s, I think that we’re in a different phase, where we can call this appropriation out when we see it.

More than the misappropriation of Indigenous knowledge, I think the bigger problem right now is that Western science continues to set itself up in competition with Indigenous knowledge — reflecting another version of the “settler supremacy” problem. Settler supremacy is built into Western science systems, but it doesn’t have to be that way. The question is how can we braid knowledge systems, combining the best Western science with the best of Indigenous knowledge in ways that don’t replicate those hierarchies of knowledge.

SL In your “Red Natural History” essay, you talk about something called “the Shift,” which may well be occurring as we speak. How are you defining “Red Natural History,” where have you seen it alive in the past and where do you see it alive today; and why might Red Natural History, as you define it, be important to the “shift”?

DGW I understand red natural history as the bringing together of the past into the present, into the future in a way that centers Indigenous knowledge — in other words, a perspective that is defined by a different kind of value system, rooted in relationality, reciprocity, respect and responsibility for the ecosystems that we all inhabit. Red natural history centers these values in ways that can allow society to shift away from the endless exploitation of the natural environment, and toward a use of the environment that is beneficial for everyone.

This is the paradigm shift that I’m working towards, along with other Native scholars who see TEK or traditional ecological knowledge as a vehicle for guiding our societies into the future. This shift is not only about the protection of Native knowledge, but also the protection of the political existence of Tribes. And this shift is in process. I know because I’m part of it. The question is to what extent it will be mainstreamed, taken seriously on a national and international scale. If we are going to see a survivable future for everyone, Indigenous knowledge will need to be incorporated into the education system at all levels, from K through 12 and higher education, into our research spaces, and into our policy spaces.

Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes) is a Lecturer of American Indian Studies at California State University San Marcos and an independent educator in American Indian environmental policy and other issues. At CSUSM she teaches courses on environmentalism and American Indians, traditional ecological knowledge, religion and philosophy, Native women’s activism, American Indians and sports, and decolonization. She also works within the field of critical sports studies, examining the intersections of Indigeneity and the sport of surfing. Dina is the author of two books, most recently the award-winning As Long As Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice from Colonization to Standing Rock.

Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes) is a Lecturer of American Indian Studies at California State University San Marcos and an independent educator in American Indian environmental policy and other issues. At CSUSM she teaches courses on environmentalism and American Indians, traditional ecological knowledge, religion and philosophy, Native women’s activism, American Indians and sports, and decolonization. She also works within the field of critical sports studies, examining the intersections of Indigeneity and the sport of surfing. Dina is the author of two books, most recently the award-winning As Long As Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice from Colonization to Standing Rock.