The planetary scale of anthropogenic climate change poses problems for the Left. How do we identify appropriate targets and build strong alliances? What resources can we use to support this building and targeting? New tactics from an array of art and activist collectives signal that institutions are sites of struggle. Collectives concerned with fossil fuels, labor, and decolonization are deploying institutions as targets and resources for radical political practice.

Multiple reinforcing systems produce climate change—capitalism, imperialism, colonialism, militarism, extractivism. The fossil fuel sector mobilizes to keep on drilling. Dispossessed communities divide within themselves over devastating and hopeless economic alternatives. States push for further exploration and amplified production to preserve their hegemony. Some countries demand the right to develop. Various groups and nonstate actors insist that we “keep it in the ground.” It’s clear that the 1 percent sacrifice the futures of the rest of us for their own economic interest. Yet the complex interworking of multiple systems makes it close to impossible to envision the politics of climate justice.

Time is running out. Climate change is happening now and future warming is locked in. The question is how fast and how much. There are no simple solutions. Food shortages, droughts, rising sea levels, record-breaking temperatures, mass migration, and war force the urgency of organization. Organizing is no longer a choice for the Left. It’s a necessity.

Some on the Left respond with refusal. Advocates of neo-primitivist lifestyle politics retreat to the forests and mountains, to DIY off-the-grid living that abandons the millions in the cities. This “not my problem” individualist survivalism reflects the ideological orientation of neoliberal capitalism. Survival-themed reality television has been big for over a decade. Others on the Left side with the things. They advocate horizontal relationships with rocks and nonlife, shift to deep time, and celebrate the microbes and weeds likely to thrive in a posthuman world. Here the genocidal mindset cultivated in the sixteenth century’s colonization of the Americas expands and turns back in on human life as a whole. The failure to value black and brown life, the inability to conceive living with and in diverse egalitarian communities, becomes the incapacity to value human life at all.

So long as the Left looks on in despair (or averts its gaze), capitalism determines the horizon of our response to the changing climate. Carbon markets, green technology, and geoengineering appear as the only way forward even as they reinforce the systems of exploitation, dispossession, and domination already dismantling the possibility of a future for the majority of the planet’s inhabitants.

The supposition that climate solutions can only be market solutions is afforded by the infrastructures and institutions that reproduce capitalist class power. The last forty years of neoliberalism hollowed out our public institutions. From the corporate capture of the legislative process, to the evisceration of schools and universities, to the widespread selling off of public land, assets, and services to the highest bidder, neoliberal capitalism sucked the life out of those components of the state that promised to serve the people. It reinforced strategies for private capital accumulation, socializing risk and privatizing reward to produce new forms of extreme inequality. At the same time, neoliberal governance intensified the coercive power of the state, amping up the police, the military, and the apparatuses of surveillance.

Neoliberal ideology rose to hegemony by seizing and repurposing existing institutions. Public institutions—such as museums, libraries, parliaments, parks, and schools—supply an infrastructure for creating and communicating common understandings of the world. They offer perspectives on politics, culture, nature, and society, delineating the limits of thought and action. Because these perspectives are essential to the maintenance of power, institutions are sites of ideological struggle.

The capitalist class relies on ideological apparatuses like museums to produce and reproduce the subjects it needs. Such subjects are classed, sexed, raced, and gendered. They are configured as primitive or civilized, exotic or everyday, foreign or “like us.” Underlying the complex of state projects that establish some as backwards and others as advanced are political and economic assumptions regarding natural development and balanced systems. Fossils elide with fuel; some people are treated as nature; extractivism signifies progress; and even systems driven by crisis and exploitation are described in terms of equilibrium. Neoliberal capitalism’s intensified competition pushes the corporate sector to ratchet up this war for hearts and minds. Museums and other public institutions become little more than apparatuses for public relations, resources for reshaping common sense according to capitalist values and priorities.

Institutions have been starved into submission by private interests. No wonder much of the Left does not recognize itself within them. But the practice deployed by neoliberals to seize institutions is now being deployed against neoliberal purposes. Co-optation goes both ways. This is the wager of the insurgent movement to liberate institutions from the grip of capitalism.

From Tactics to Movement

The cultural commons institutionalized in museums, libraries, parliaments, and universities as well as in social forms, practices, images, and ideas is collective. As Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri argue in Commonwealth, the third volume of their influential Empire trilogy, “institutions consolidate collective habits, practices, and capacities that designate a form of life.” This consolidation is not without division. Hardt and Negri point out that “institutions are based on conflict.” They are sites of struggle over who and what counts, over the ways we see and understand our collective being together. Dominant forms of power try to ensure that we see the way they want us to see. Just as the settler colonialism and chattel slavery at the heart of the United States gets pushed aside in celebratory depictions of the American experience, so too does the capitalist class power operative in museums. Since the nineteenth century, robber barons, financiers, oil magnates, and fossil fuel oligarchs have weaponized cultural institutions, presenting exploitation, hierarchy, and dispossession as if they were natural. An array of artists and activists are refusing to cede the cultural commons to the capitalist class. Their tactics suggest an insurgent movement to liberate institutions.

Institutional liberation emerges from the recognition of the collective power already concentrated into institutions. The cultural commons is created by all of us in our conflictual diversity. We make it. Cultural knowledges, symbols, images, and practices are social products, not property belonging to the 1 percent. Rather than overburdening ourselves with the overwhelming task of inventing entirely new political and social forms, contemporary artists and activists are reclaiming the cultural commons. Engaging with existing institutional forms, they fight on, through, and for the terrain of the common.

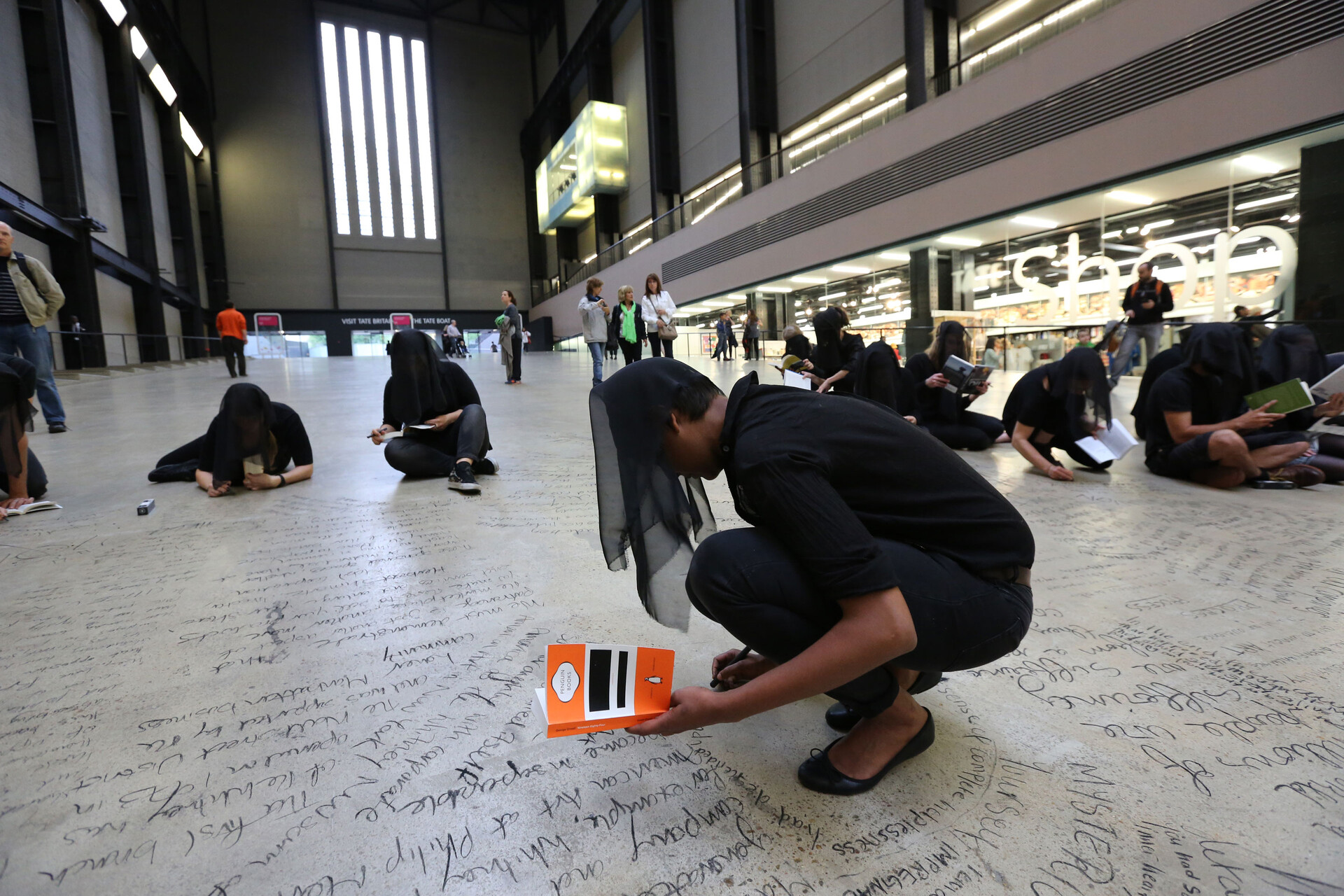

Activist art collectives such as Art Not Oil, BP or Not BP, Gulf Labor, Liberate Tate, The Natural History Museum, Occupy Museums, Decolonize This Place, and others deploy a common tactic: commandeering museums. Strategically intervening in major museums that have been captured by capitalist interests, these groups reclaim the cultural commons. They treat the names, symbols, perspectives, and ideals of institutions like the Tate Galleries, Guggenheim Museums, and the American Museum of Natural History as sites of political struggle. While some engage institutions in the service of climate justice, others use them as platforms for anticapitalist mobilization. Despite their differing objectives, rhetoric, and strategic positioning, their strength comes from their common practice of treating the museum as a site of insurgency. Institutions’ names, symbols, perspectives, and ideals become objects of political struggle. Whether a group engages institutions as a front in anticapitalist struggle, in order to create a counterpower infrastructure, or in the service of climate justice, what is noteworthy in the practice of contemporary activist art collectives is the emergence of the museum as a terrain of insurgency.

Institutions are not monolithic unities. They are complex multiplicities, split within themselves and between themselves and their settings. Museums have custodial staff, administrators, curators, IT personnel, fundraisers, directors, donors, trustees, and visitors. They also have their broader cultural position, their reputation as sites of authoritative knowledge. This makes them sites worth seizing. When art activists commandeer a museum, they split it from within. The already existent divisions within the institution are activated. Anyone affiliated with the museum is forced to take a side: few or many, rich or poor, past or future? By occupying institutions, identifying allies on the inside, empowering employees, working with whistle-blowers, leveraging legal grey zones, and strategically mobilizing the symbolic power of key constituencies, activist art collectives redeploy the arsenals of power that have already been stored. The institution is liberated.

The insurgent movement for institutional liberation generates counterpower by strategically mobilizing the power institutions already have. Major cultural institutions exert large-scale political, economic, and cultural influence. They influence how we see. They legitimate particular players. They have the power to influence popular values and ideals, but they refuse to use this power on behalf of the people. When artists and activists target these institutions, they take advantage of their scale. Museums’ concentrations of cultural capital are seized and redistributed back into the common. No longer can museums function to legitimate corporations, the fossil fuel sector, or particular colonial projects. They are demarcated as battle zones.

Institutional liberation extends beyond museums. It is part of a broader insurgency to capture and retake the common. The Dutch artist Jonas Staal’s projects seize and stretch the forms of the university, the parliament, the summit, and the (non)state. Staal pulls out the scripts and symbols constitutive of these forms, redeploying them in people’s struggle. The Undercommoning project, put together by a semi-anonymous alliance of fugitive knowledge workers, seizes the means of knowledge production, urging revolution “within, against, and beyond the university.” Drawing from traditions of militant inquiry, the project recognizes the university as “a key institution of globalized racial capitalism” that “therefore cannot be ignored or conceded as a field of struggle.”

Free the Institutions!

Refusal and subtraction have been disastrous as Left political tactics. They have surrendered the power aggregated in institutions to capital and the state. The tactics of institutional liberation treat institutions as tools, weapons, and bases of political struggle. They take on and over the institution’s radical premise: the collectivity and futurity that underpins any collection. The force that comes from organization, collectivity, and institutionality, the symbolic power that accompanies and exceeds aggregation, becomes a resource for the Left, a resource that enables us to combine and scale.

Many can be more powerful than few, but only when they are organized. Contemporary capitalism relies on dispersing us into powerlessness. It celebrates individualism and uniqueness, as if one person alone could bring down the fossil fuel economy. This individualist dream entraps us in the nightmare of accelerating inequality and ecological devastation. Institutional liberation claims the power of collectivity, the necessity of alliance, combination, and commonality in struggle. This is why we see today the appearance and reappearance of common images, names, and tactics.

The various projects we see combining into an emergent movement for institutional liberation do not value critique qua critique. They turn the institution against itself, side with its better nature, and force others to take a side. They look for allies, “double agents” already working within the institution, reinforce them, and in so doing activate the power that is already there. Institutional liberation is not reformist. It does not simply expose our complicities with state and capital. It directs its critical perspective in the service of a broader political movement, treating institutions as forms to be seized and connected into a counterpower infrastructure.

The liberation of institutions will not result from any singular procedure. It depends on sustained pressure, a commitment to long-term struggle. More than a critique of institutions—because, face it, at this point the inequality, oppression, and violence of the capitalist state is not a mystery to be solved but a system to be abolished—institutional liberation affirms the productive and creative dimension of collective struggle. Our actions are not simply against. They are for: for emancipation, equality, collectivity, and the commons.

Institutional liberation is not a messianic event. It is the building of counterpower infrastructure. Once they take the side of the common, institutions liberate themselves from capitalist interests endeavoring to control and exploit them. So institutional liberation isn’t about making institutions better, more inclusive, more participatory. It’s about establishing politicized base camps from which ever more coordinated, elaborate, and effective campaigns against the capitalist state in all its racist, exploitative, extractivist, and colonizing dimensions can be carried out. This takeover will not happen overnight. But it is happening now at an international scale, accumulating force and momentum with every repetition of a common name and image, every iteration of associated acts: red lines, red squares, arrayed tents, money drops, blockades, occupations.

Not An Alternative (est. 2004) is a collective that works at the intersection of art, activism, and theory. The collective’s latest, ongoing project is The Natural History Museum (2014–), a traveling museum that highlights the socio-political forces that shape nature. The Natural History Museum collaborates with Indigenous communities, environmental justice organizations, scientists, and museum workers to create new narratives about our shared history and future, with the goal of educating the public, influencing public opinion, and inspiring collective action.

This text was originally published in e-flux journal #77 (November 2016).