This is the time of crisis. In communities all across the world, the roiling heat and flames and the surging seas and storms of the climate crisis are upending lives and communities unabated; the brutality of state and police violence and supremacy are becoming ever more cruel and brazen; and the ravages of COVID-19 are only just beginning to ebb. These crises are overlapping—colliding, even—in time and space, felt and experienced most acutely in poor and working-class communities of color. To see the time of crisis unfold is to see the concept of “sacrifice zones”—the notion that capitalism requires certain communities to bear a disproportionate share of global capitalism’s myriad costs and that those areas are delimited by long-standing racial hierarchies—become visceral and impossible to deny. How else might one explain the brazen and very public examples of police violence in retaliation against Black Lives Matter protests, the surging waters of record hurricane and wildfire seasons, and the significantly higher per capita death rates of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color overlapping in the same handful of communities last year?

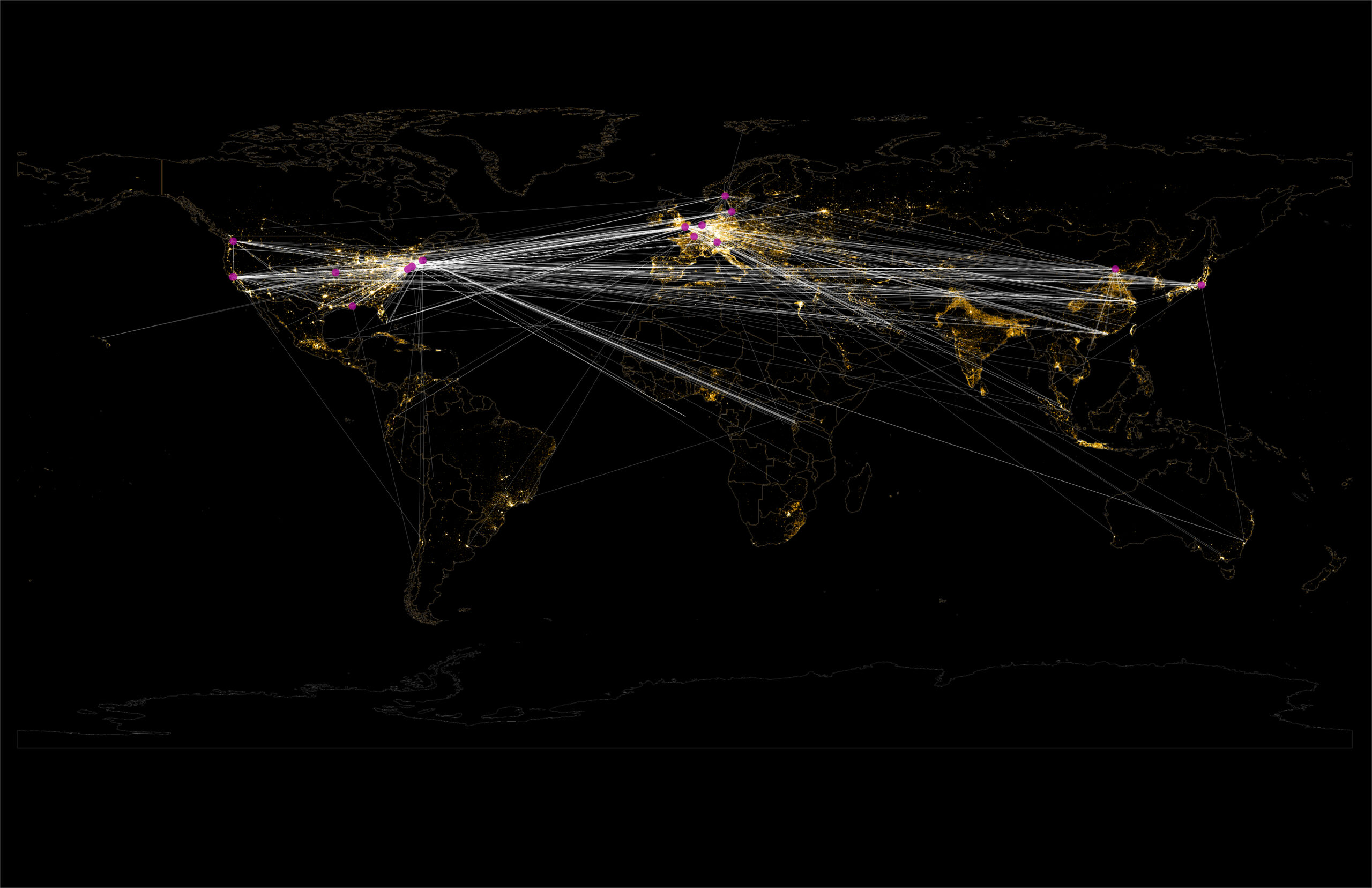

This stark reality is a present foretold by Naomi Klein in This Changes Everything, where she writes that “running an economy on energy sources that release poisons as an unavoidable part of their extraction and refining has always required sacrifice zones—whole subsets of humanity categorized as less than fully human, which made their poisoning in the name of progress somehow acceptable…our political-economic systems and our planetary systems are now at war.” The time of crisis is an inevitable result of a world organized by global and racial capitalism and governed by the Global North. And architects, landscape architects, and other built environment professionals have been working overtime to make it all possible.

Design without Criticality

Contra to the self-mythology and triumphalist rhetoric that defines much design scholarship, the design professions—architecture, landscape architecture, urban design, and city planning—are indistinguishable in their aims, operations, and outcomes from the rest of the professional services industry. While design has always found itself tethered to and bounded by varying forms of capitalist hegemony, each political economic era is contingent and historically situated—and it would take a series of books to even begin exploring each of them in equal measure. This text zeroes in on the racial and economic order that capitalism has produced and continued to produce in the twenty-first century, asking how design is bound by and tasked with laundering this order through the built environment.

To understand the contemporary formation of capitalism and design (and landscape architecture in particular), as well as the inevitable crises they produce, it is important to begin from a simple premise: that the design professions are not capable of reconciling their ethical and material contradictions—of urban greening and ecological gentrification, of high-carbon luxury real estate development and the LEED and SITES building efficiency certification programs, of state-led investments in urbanism and the public realm with state sanctioned violence and racial hierarchy. Put another way, the design professions are best understood as materially and conceptually aligned with multi-national consulting firms like McKinsey & Company. While their instruments differ—McKinsey focuses on organizational structure and optimizing corporate and regime finances, design firms on the built and natural environment—they pursue commissions and contracts from the same pool of public and private capital in many of the same cities and nations. They are also often complicit in some of the most egregious forms of human immiseration that capitalism has to offer. Perhaps most strikingly, they are all involved in laundering these power structures in their work.

In a set of professions enamored with star power and committed to myths of lone, creative genius and of “great person” theories of history, this analogy allows one to reconcile specific questions like: how is it that a massive, global firm like AECOM can justify building climate adaptation infrastructure and prisons? How can a firm like HOK categorize its work as “justice” driven as it too builds prisons and designs headquarters and infrastructure for the fossil fuel industry? How can a practice like be viewed as a leader on climate change as it develops high-carbon, eco-apartheid luxury projects for autocratic regimes in the Middle East? How can a practitioner like Bjarke Ingels rationalize building some of the century’s most celebrated social housing and developing eco-tourism projects for a genocidal, authoritarian regime in Brazil? Though its manifestations vary from era-to-era and place-to-place, design tends to go where capital flows. I don’t know when the myth of designers as agents of change began, but I do know that it’s time to kill it. We might begin by focusing on the unspoken mission of design education and practice—which often amounts to an attempt to condition students and young practitioners for a lifetime of exploited labor, detached from any critical relationship to the role their professions will play in instrumentalizing and aestheticizing global capitalism around the world. This becomes plain to see when one scrutinizes the literal texts of post-critical theory in architecture, in which Somol and Whiting write that “setting out this [post-critical] program does not necessarily entail a capitulation to market forces, but actually respects and reorganizes multiple economies.” There, and in an entire generation of design writing that followed, the often-submerged ideological project of contemporary design practice becomes foregrounded: to abandon the struggle for alternative ways of contesting, subverting, and confronting global capitalism, and, instead, to embrace the opportunities it provides to designers to experiment with form, aesthetics, and building. By taking critical theory and political economic analysis off the table, designers have found themselves more concerned with the signals (e.g., biodiversity loss) of this century’s overlapping crises than its root causes.

This is what one might refer to as a permission structure: without the fear of reprisal or critical analysis, designers are now free to conspire with the forces and institutions of global capitalism, white supremacy, and other instruments of immiseration—and to do so while cloaking themselves in the rhetoric of climate, racial, and economic justice. It is what drives designers to dedicate scholarly resources to affordable housing over public and social housing, geoengineering and ecomodernism over ecosocialism and fossil fuel abolition, and public realm projects that include carceral infrastructure instead of those formulated by prison abolitionists. Indeed, such alliances are not only permissible. They are celebrated in design culture as evidence of one’s savvy—a realpolitik of sorts, wherein making a terrible project or idea into a better one is seen as the apogee of success. This collaborationist ethos has always been the case and it has always been sanctioned by the institutions of the profession. But without a formidable left to counter the market fundamentalism of design’s new center-right, self-critique and reflexivity has largely vanished—and with the profession’s gaze turned inward, external critiques are easily dismissed. From within the design professions, there is no need to consider what it means to practice ethically in this world because landscape architecture has no ethical commitments, only rhetorical ones.

In this reading of contemporary design practice, the mutual benefit of the post-critical professions becomes clear: capitalism needs design to adorn, instrumentalize, and launder its ways of seeking new forms of exploitation and extraction—to obscure the ways in which it extracts and immiserates through coded terms like sustainability, resilience, and progress. Design needs capitalism to operate. Why contemplate a confrontation with capitalism when it not only affords an opportunity to bolster the field’s material and cultural position, but is required for the field to exist at all?

Design with Movements

Designers have not yet begun to grapple in any meaningful way with this inward turn. Nor have their professional organizations acknowledged—let alone developed alternatives to—its wholesale capture by what Sam Stein refers to as “the real estate state.” Beyond the sanctioned practices of these organizations, however, more radical architects and landscape architects have begun to imagine alternative ways of working through collectives like The Architecture Lobby and Design as Protest.

Yet, the world that Green New Dealers intend to create must literally be built. More important, the buildings, landscapes, public works, and infrastructures of a just, post-carbon future will be one of the primary ways in which most people experience something like the Green New Deal—through the production of luxurious and low-carbon social housing, through the provision of high-service and decarbonized public transportation, and through the reconfiguration of how and where we live. To become contributors rather than obstacles to this work, the design professions must find new ways of working.

To build on the work of Green New Dealers and the climate justice movement, we have to find ways of breathing new, more radical life into the spaces where an anti-capitalist design agenda might be forged. To do so, we must first ask: how might an insurgent set of practices make itself more useful and relevant to the various movements for justice that are leading the movements for a Green New Deal, a Red Deal, and a Red, Black, and Green New Deal in our time of unending crisis? This alliance with insurgent movements for justice is the heart of this essay series—one that begins to scope out a common project in design theory, history, and practice for advancing an agenda of planetary survival, flourishing, and collective struggle. For me, at least two obvious rejoinders to this question emerge.

One is to simply take a more expansive view of what constitutes architecture, landscape architecture, and design more broadly—to look beyond the sanctioned practices of credentialed professionals, concentrated in the Global North, and to look to more radical histories and contemporary examples of practice in anarchist, Indigenous, and other anti-capitalist traditions. For instance, landscape architects could dismantle their troubled fascination with figures like Frederick Law Olmsted—whose masterpiece, Central Park, was predicated upon the eviction of residents in Seneca Village, a thriving Black community in Manhattan at the time—by viewing communitarian, agrarian “Diggers” as their true origin story. Or perhaps they might look to the traditional ecological knowledge of Indigenous nations in ways that elevate, rather than extract from, their work within the professions. Doing so can expand both the boundaries of who and what constitutes the design professions and offer an on-ramp to a more radical set of practices than markets and global capitalism will ever permit.

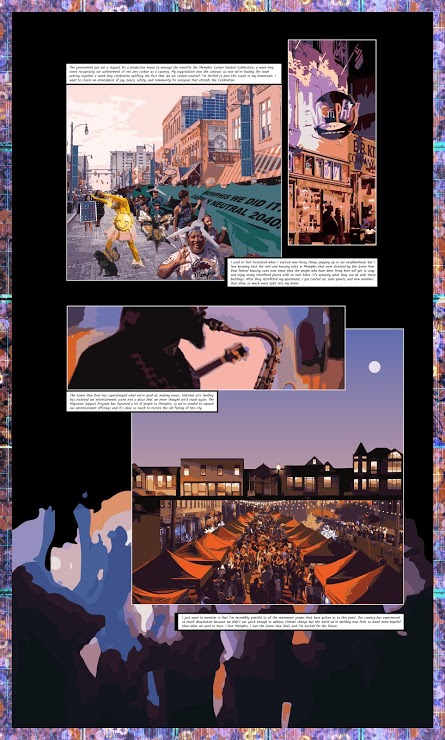

The other is, through a form of power analysis, to think critically about the instruments and institutions at our disposal and, particularly in the academy, to work through how they might be made more useful in this time of crisis. For me, this has meant using the studio and the McHarg Center, which I direct at the University of Pennsylvania, as spaces to align our work with that of local climate, housing, and racial justice leaders—to develop fictions and futures together. That work has centered on three industries in three regions: the carceral, fossil fuel, and industrial agriculture systems; and the Midwest, Appalachia, and Mississippi Delta, linked together through the framework of the Green New Deal.

In these studios, I rely on Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s analysis of institutions and their role in reproducing a particular, self-serving ideology in Manufactured Consent. They write that “the beauty of the system is that dissent and inconvenient information are kept within bounds and at the margins, so that while their presence shows that the system is not monolithic, they are not large enough to interfere unduly with the domination of the official agenda.” Though they are writing about the media ecosystem and elite capture within it, their analysis holds for much of design education. Indeed, nearly all elite schools of design are funded in part by the same class of global elites at the core of Herman and Chomsky’s analysis—and Penn is no exception. In these studios, I use the concept of platforming in both material and instrumental ways. Materially, it relates to the ways in which the studio serves as a stage for elevating the demands of the climate justice movement—demands that, at best, are placed on the fringe of most design programs and, at worst, are banished altogether as unrealistic and divisive. Instrumentally, it relates to the ways in which this studio serves as a platform for students in their final year of study to begin building alternative career pathways for themselves. Students use the exposure and relationships these studios have provided to find modes of practice outside the private, client-driven practice of contemporary design.

This latter point has been among the most generative throughout the Designing a Green New Deal studios. The design studios have not served as a way for me to reproduce the exploitative model of a “studio” or “firm” book, in which the unpaid and often un/under-credited is used by a critic or principal to “write” a book. Rather, they have led matriculating students to become go-to experts in the climate and environmental media, where they are developing ongoing projects with the local movement groups they met and leading studios and policy-focused work around the Green New Deal elsewhere.

Throughout these studios, students used ethnographic methods to develop storytelling vehicles, climate fictions, and other alternate futures with a variety of movement-led groups in each region—and their ultimate deliverables varied wildly. There was a “Workbook for Dreaming” aimed at democratizing the design process and based on the Fumbling Towards Repair workbook, a prison-to-rural electric co-operate manual, and a climate-driven community farmer’s almanac in Appalachia. There was a cookbook, a children’s book, and a fictional NPR podcast, each linked to climate migration, agricultural co-ops, and prison abolition in the Midwest. There was a series of zines, oral histories, and character development projects in the Mississippi Delta. Rather than a final review, students were asked to create a to house their atlases and speculative futures work and to lead a series of panel discussions moderated by invited experts Beka Economopoulos, Bryan Lee, and Anjulie Rao.

In a sense, these studios have become extensions of a larger critique of the design disciplines first outlined in an essay I wrote for Places Journal titled “Design and the Green New Deal.” They have focused on rural communities already operating within the sacrifice zones rendered by global capitalism and often beyond the reach of contemporary practice. They have also pushed back against the ways in which capitalist realism frames what constitutes “pragmatism” in the design professions—a term often used to describe projects that are eminently buildable, even if their construction is predicated on the preservation of a status quo that all but ensures social and ecological immiseration. Put another way, the DGND studios have sought to question whether it is pragmatic to uphold the very systems of exploitation and immiseration that wrought planetary climate change in the name of building out one’s portfolio.

Coda

I am writing this as a coda because this sort of work is always precarious. As a junior and non-tenure track faculty member in particular, my work at the McHarg Center is subject to the whims of administrators, donors, and the university’s politics. The DGND work is in a state of constant peril and real questions remain about how long it may be allowed to continue. But taking risks like this is the only justifiable reason to locate oneself at an institution like Penn—because it offers resources, power, and a platform that can be used to point the design disciplines in new directions. These are directions that would likely not have been explored if not for the Green New Deal work I have led in the Center over the last few years. While not everyone is well-positioned to take such risks, those of us who are have a responsibility to do so—whatever the professional consequences might be.

Billy Fleming is the Wilks Family Director of the Ian L. McHarg Center in the Weitzman School of Design. Billy is co-editor of An Adaptation Blueprint (Island Press, 2021), co-editor and co-curator of the book–and now internationally-traveling exhibit–Design With Nature Now (Lincoln, 2019), and author of the forthcoming Drowning America: The Nature and Politics of Adaptation (Penn Press, expected 2022). He co-authored a series of policy briefs that led to the “Green New Deal for Public Housing Act” and is lead author of The 2100 Project: An Atlas for the Green New Deal.