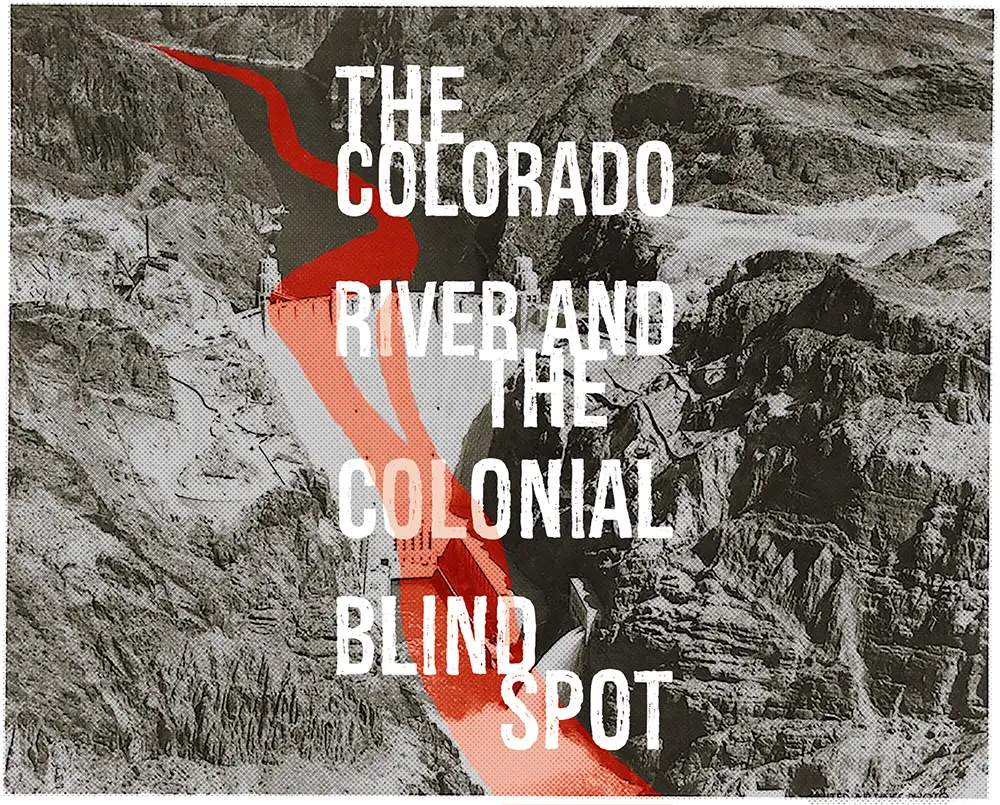

Video & Highlights: The Colorado River and the Colonial Blindspot

The Colorado River is in crisis and environmental scientists are weighing in. But why are so many refusing to name the culprit — focusing on the impacts of climate change

read more...

The Colorado River is in crisis and environmental scientists are weighing in. But why are so many refusing to name the culprit — focusing on the impacts of climate change

read more...As one of The Natural History Museum’s inaugural Red Natural History Fellows, Diné geographer Andrew Curley is examining the contestation of water rights within the Colorado River basin. In this edited conversation with NHM’s Steve Lyons, Curley takes on the colonial structures that shape mainstream trends in environmental science, asking how academic research cultures and institutional practices contribute to the replication of settler-colonial relations in the United States.

Steve Lyons (SL) I want to start with the question of Indigenous erasure. In your recent “Red Natural History” essay on “Dinosaurs, Eugenics and Collapse,” you explore how Western scientific understandings of the world are premised on a colonial blindspot—a kind of inability to see how colonization transformed the world on the one hand, and an inability to see how Indigenous peoples have had agency in these processes on the other. This blindness has real consequences for how natural historians understand how we got to the current crisis and where we need to go from here.

In my mind, your new work on the Colorado River hammers this home. You talk about how contemporary environmental science participates in naturalizing settler-colonial infrastructures like dams and cities—not only by accepting settler-colonial units of analysis like the acre-foot, a quantification necessary to attribute value to the land and water as a resource, but also by serving the needs of the settler-colonial “water managers,” who are responsible for maintaining the legal frameworks that have been disastrous for the river.

Could you tell us about what is taken for granted in the mainstream of your discipline? And what are the risks of accepting these basic assumptions? What role do scientists and scholars play in legitimizing colonial water laws and in preserving these colonial intrusions, making them seem like inevitable parts of the landscape, rather than as parts of the problem?

Andrew Curley (AC) Working within academic institutions, it is striking that they are uncritical or unreflective of their own culpability in the production of a colonial epistemology. I think this is consistent with the premise of the “Red Natural History” project, where we are thinking about how people who define their work within a narrow understanding of science replicate and reproduce colonial divisions and understandings of the natural landscape, which Kwakwaka’wakw scholar Sarah Hunt calls a “colonialscape.”

We’re surrounded by this colonialscape. We’re subsumed in it. I look around me and I have mountains that are all named after settlers who have no relationship with the place. This is a dominant feature of settler-colonial geography, and one that is largely left uncriticized among white settler scholars. This seems like an obvious point, but it seems so profound for the people who actually are critiqued, as if they’ve never thought of this before.

The Colorado River is artificially divided between these political entities called States, which claim a strong interest in the river: Arizona, California, Nevada, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico. These states are artificial, but they have real political leverage and power to access the waters. These states made an agreement in 1922, only 100 years ago, to divide the entirety of the river among themselves, creating a boundary at a place called Lees Ferry, which separates two basins: the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin. Contemporary environmental scientists measure the river according to these artificial political divisions, naturalizing the way that the state governments divided the river in 1922.

What is more, following the division of the river, there were a number of violent intrusions onto the natural pathway of the river in the form of huge hydrological dams, some of the biggest and most notorious in the world, including the Hoover Dam. The purpose of these dams was not only to generate electricity, but also to create reservoirs to create a cache of water for urbanizing areas that did not have a natural access to the river, including Phoenix and Las Vegas.

Scientists legitimize those dams when they organize their studies around the water levels in reservoirs that are recent intrusions onto the river. I am interested in how contemporary environmental scientists often conflate two ways of understanding the river. First, they take the status of the river as it exists now, after this violent scramble to move the waters all throughout the West for agribusiness and then urban expansion. And second, they consider the implications of climate change on the river by comparing it to the river as it existed in 1400, 1300, 1100, as if we’re talking about the same thing. We learn very little about how the river transformed by tracing the fluctuation of precipitation in the region or the longstanding weather patterns. What really transformed the river was colonialism. In the environmental sciences, you can’t point to that. You have to point to everything else.

This begs the question: what is the value of this science if it can’t even name the culprit? I think it’s farcical that people in my business pretend like they’re doing science, while excluding the history and contemporary existence of colonialism. If you were to take an objective viewpoint, you would immediately see that the origin of the water crisis on the Colorado River isn’t climate change. It is the overuse of the river. And that overuse goes back to the late 19th century, when agribusiness began developing along these tributaries.

SL You’re touching on a few points I wanted to raise. One was about how science has a material effect on the world. As scientists respond to the changing “colonialscape,” as you put it, they risk reproducing, strengthening, and legitimizing this colonialscape. You’re building a critical picture of what The Natural History Museum describes as a dominant imperialist tradition of natural history—a natural history that naturalizes settler-colonial infrastructure, which preserves the system that’s driving the very crisis that it seeks to understand.

I’m wondering if you can help us understand how this actually works in practice. How, in your experience navigating the university, for example, are students and researchers being trained or incentivized to participate in the maintenance of the settler-colonial regime? It’s clearly not just that scientists are immoral people. There’s an entire apparatus that privileges some methodologies above others, as well as the kinds of questions that get asked and the kinds of research that gets funded.

AC I’m in a geography department because I couldn’t do the work I wanted to do in sociology, which is the discipline I was trained in. Critical geography has shortcomings, which myself and others are quick to point out, but in disciplines like public policy, economics, or sociology, scholars are actively denying Indigenous voices and concerns. Scholars in these fields tend to imagine themselves to be in dialogue with policymakers, both in the sense of informing policy and sharing glasses of wine. They ignore Indigenous claims and issues because Indigenous issues will never be policy priorities under a colonial regime. Working on the rights and issues of Indigenous Peoples is not going to get you a seat at the table with lawmakers.

As you said, these aren’t immoral people. Many of them are really nice. But colonialists don’t always come in pilgrim hats or on wagons with oxen that are easy to identify. They come to your coffee shops. They run the cooperative markets selling alternative foods. The problem isn’t the people, but the options available to people who work a society premised on settler-colonialism. There is a whole culture of practice that results in the replication of the colonial system.

In the case of scientific research, a lot of it comes down to funding. The National Science Foundation and other major funders that supply the material basis for research in the United States prioritize universalizing claims, questions that address a majoritarianism issue, which will always be the settler-colonial issue. So if I go to the NSF and say I want to research Navajo water issues, they will ask: “What’s the broader implication of this research? How will it help non-Navajos, i.e. settlers, deal with their water issues? If we’re going to give you money, you have to convince us that it benefits the ‘larger society’,” by which they mean the white colonial society.

When Indigenous work comes down the pipeline, funders can get really defensive. This work runs up against oppositional forces, doesn’t get a lot of funding, and Indigenous scientists and scholars are forced to work within a whole institutional culture that understands science and Indigenous issues as incommensurate. This is not a new phenomenon, and I’m not the first person to point it out.

Writing in 1959, the critical sociologist C. Wright Mills used the term “abstracted empiricism” to describe how science was just doing its thing, publishing results without asking important questions. Mills wasn’t even referring to that Indigenous, Black, or Latinx issues that we are now considering. He was just saying that science had become a kind of cynical, self-funded industry, interested only in publishing results, getting funding, and judging success by the number of citations, regardless of the quality of engagement and the amount of funding received. I don’t think it’s an accident that a lot of people have become very upset with universities, accusing them of being distant from the broader experiences of people. There’s a lot of truth to it.

SL In your new writing on the Colorado River, you take on the abstracting tendencies of Western science, contrasting them to the grounded and specific place-based knowledges of Indigenous Nations. I’m wondering if you can expand on your critique of abstraction. What are the problems with abstraction, or, if not abstraction itself, what are the uses of abstraction that you take issue with?

AC In 1987, Derek Sayer wrote “The Violence of Abstraction,” and while he was writing in a totally different context, the title is really good. What is the violence of abstraction? And in the case I’m researching, what is the violence of abstraction in the scientific research on the Colorado River? In this case, what becomes abstracted is water. Within the colonial theory of knowledge, water becomes quantified through the measure of the “acre-foot.” And it is in this quantifiable unit that water can become tradable, sellable, and negotiated as the basis of a right of use or right to exploit. This quantification was necessary before the water could be moved out of the landscape upon which it flowed, which was the landscape that Indigenous Peoples had experienced and learned from before colonization.

I should stress that “Indigenous” is not a homogenous thing. We’re using the term in contradistinction to settler society, but there are different Nations with their own knowledge systems. There are nearly 30 federally recognized Tribes that have some sort of claim to the Colorado River or its tributaries. Each of these nations (and internally within them) have different kinds of experience, depending on where they live and what kind of uses they’ve needed from the water. I can’t speak for Havasupai. I can’t speak for Hopi. I can’t speak for Zuni. I can’t speak for Ute. I can’t speak for Tohono O’odham, or any of these other Nations.

But thinking about it from the Diné perspective, from the Navajo perspective, water is understood in different forms, depending on place and space. It can be a pool of water in a canyon. It can be a spring that’s known, that’s drawn from aquifer water. It can be surface water, a river, a tributary wash. It can be a large water source, like what is now called the Colorado River. Those are all different kinds of water that exist on the landscape. And then there’s precipitation—different kinds of rains. You have the hard rain, the light rain, the snow. The planting seasons are tied to observations of water, both in the air and on the landscape, over generations of experience. This is science in my definition.

SL In your essay for our Social Text dossier, you write that “Conceptual colonialism creeps into everyday sciences, especially the natural sciences, where Indigenous people play Tonto-like roles to the real world work done by Lone Ranger scientists.” Later in the text you argue that in contemporary environmental discourse, this role is also given to Traditional Ecological Knowledge, which, like Tonto, is treated like “something supporting but not fundamentally challenging to Western epistemology.” Can you explain this metaphor, as well as how you see “TEK” being deployed and domesticated in settler science and scholarship?

AC The Tonto-Lone Ranger metaphor is meant to highlight a dynamic we see in academic research culture: you have the Indian sidekick or the Indian paid researcher, but the Principal Investigator (P.I.)—the person running the show—will be a white person who is interested in solving settler-colonial questions, like “How is Phoenix going to develop a more sustainable use of water?” Or, “How are we going to deal with the rural agrarian interests that are inheriting a legacy of land deprivation between Tucson and Phoenix?” The P.I. will include Indigenous Peoples in their grant, either to get more grant funding by claiming that the project is supporting a diversity of scholarship, or to somehow assuage their colonial guilt. But they won’t actually deal with Indigenous questions.

There are two main problems with how “traditional ecological knowledge” gets used. First, it is often used in a way that homogenizes knowledge systems, as though there is one Indigenous perspective. Even amongst ourselves in the Southwest, we have very different understandings of the world around us and very different histories. Lumping all of these understandings together as “TEK” is already a disservice to us. Second, TEK tends to only get used when it supports the existing colonial epistemology. If my traditional knowledge suggests that your whole approach to the environmental question is wrong, it will not have the same kind of leverage as it would if it suggests that we’re also seeing something that scientists are seeing.

SL In the current struggles over water rights on the Colorado River, how would you distinguish between the kinds of questions that are being asked in settler society and those that are being asked on the Navajo Nation, for example?

AC This is a harder part of the question to answer because it requires me to go out into the communities and get a sense of what people’s water concerns are and how they are not being addressed by the colonial water regime.

I attended a couple of forums recently on a proposed water settlement between the Navajo Nation and the state of Arizona. The presenters were water attorneys, who were trying to explain to the people what water rights are, what acre-feet are, all of these things that scientists and policymakers are concerned with. People sat through five hours of presentations before they had a chance to weigh in with their concerns about the overuse of water for industry, the depletion of aquifer water for the coal industry on the reservation, the lack of water security in the household, uranium contamination from previous mining activities around the reservation, and the cost of water.

On the reservation, people in the Navajo Nation are concerned about water security and water quality. And so they’re thinking about where they are getting their water from. What kind of water is it? Is it something that they can feed to their livestock? Is it something that they can consume in the household? Are the wells producing water? Do they need to pipe it in? Do they need to go into the city and buy water in jugs through these filtration stations that you have outside of grocery stores, or even in these plastic containers?

If you go outside the reservation world, you’re not going to hear the same questions. You’re going to hear about rights, diversions, reservoir levels and political agreements between the state of Arizona and the other Colorado River basin states. For the states and policymakers, the whole conversation about Indigenous water issues is about settling Indigenous water claims to the Colorado River. What they need to know is how much water Indian people are going to claim, because the whole system relies on all of these exact numbers fitting into this larger puzzle. And the pieces that are missing from that puzzle are in the Indigenous water claims. They’re unknown. They’re not part of the system yet.

SL In your work, you make a very strong claim that traditional knowledge or Diné knowledge has scientific merit beyond the moral or ethical obligations that ground it. You write that “this isn’t some mystic understanding of water and the land. Their knowledge is practical and necessary for survival.” Where Western science or colonial science has so often denigrated Indigenous understandings as mystical mumbo jumbo, your work is exposing how so-called “objective” scientific claims are built on mythologies, among them the myth that natural processes can be seen outside of the social, economic, legal and political and historical processes that shape them. This is central to the project that we’re naming “red natural history.”

I’m wondering how you understand “red natural history.” Where do you see its outlines? What are the values or normative claims that should ground red natural history? And what do you think needs to be done with the colonial institutions that already exist?

AC That’s a big question. I think what is interesting about this idea of red natural history is that it asks us to confront not only the ideas, but also the institutions that support those ideas. Ideas don’t exist in a world without institutions that support them. Take museums, for example. The role of museums is to tell a story to a certain kind of public. But in mainstream natural history museums, those stories often reinforce colonial narratives. Natural historians are brought in to naturalize colonialism—to say that the situation we are in was inevitable. This reproduces colonial violence on a regular basis.

In the university, the institutional context I work within, the research I am most frustrated with is coming out of the traditional disciplines. I use the word “traditional” here to refer to the colonial sciences, even geography, which was an imperial science, and continues to be in many ways, as well as anthropology, sociology, political science, economics, business. All of these disciplines really need to be critically reevaluated. In the neoliberal university, these disciplines tend to attract the most majors because they have a reputation for preparing students for “real world” jobs. But “the real world” is a colonial world. When people ask “how does this work in the real world?” what they mean to say is, “put away all these ideas of a better future and just focus on how to survive in the world that exists around you.” I think this is a real disservice to students. It makes 20 year olds cynical about changing the world.

So what can we do about it? While the stuff coming out of those research disciplines is frustrating, I am most interested in the work that is coming out of the more marginalized disciplines, like Native American/American Indian studies. My colleagues in Native American studies are teaching me to unlearn some of the things I learned from my training in sociology, and to learn how to think through and with Indigenous epistemology.

Returning to the Colorado River, what Native American studies provides are tools for us to conceptualize ourselves outside of the bind of the existing water rights regime. I think this is necessary—and may even be inevitable. If we continue to avoid addressing the finiteness of water, sooner or later we’re going to be confronted with it. Things that are seen as unmovable and concrete today, like the Colorado Compact and the division of the waters between the states, might evaporate. To imagine other possibilities, which I think is the basis of scientific inquiry, we need to push against this mythology of progress and domination that orients colonial science, and to start again from grounded observations about the world itself.

Andrew Curley (Diné) is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geography, Development, and Environment at the University of Arizona and a 2023-25 Red Natural History Fellow. His research focuses on the everyday incorporation of Indigenous nations into colonial economies. Building on ethnographic research, his publications speak to how Indigenous communities understand coal, energy, land, water, infrastructure, and development in an era of energy transition and climate change. Curley’s first book Carbon Sovereignty: Coal, Development, and Energy Transition in the Navajo Nation (University of Arizona Press) came out in 2023.

Andrew Curley (Diné) is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geography, Development, and Environment at the University of Arizona and a 2023-25 Red Natural History Fellow. His research focuses on the everyday incorporation of Indigenous nations into colonial economies. Building on ethnographic research, his publications speak to how Indigenous communities understand coal, energy, land, water, infrastructure, and development in an era of energy transition and climate change. Curley’s first book Carbon Sovereignty: Coal, Development, and Energy Transition in the Navajo Nation (University of Arizona Press) came out in 2023.

This panel explores the role that Western science plays in naturalizing the colonial intrusions that produced the contemporary water crisis on the Colorado River, revealing solutions to the crisis that are unimaginable from the settler-colonial view.

read more...

This virtual event series brings together scholar-activists, scientists, natural historians, conservationists, water protectors and land defenders to define a natural history for our world in crisis.

read more...

A new national environmental justice art campaign aims to metabolize grief into collective strength and community power.

read more...