Across the United States and around the world, monuments to racists and genocidal colonists are being toppled, thrown into rivers, vandalized, and quietly removed. Responses to these actions vary widely. Some on the left celebrate them as meaningful acts of refusal. Others disregard them as merely symbolic gestures, acts of erasure that obscure the terrain of struggle, making people feel like they’re changing something without changing anything at all. On the other side of the political divide, right-wing conspiracists interpret monument removals, the integration of “critical race theory” into educational curricula, open borders for refugees, and Indigenous land claims over privately-owned and federal lands as part of one coordinated movement to eliminate the white race—a conspiracy that some call “the Great Replacement.”

If the narrative of a Great Replacement has been a rallying cry for the far right—a highly effective means of driving a division between ethnonationalist patriots and the forces, tendencies, and movements that undermine their “sovereign claim to the land,” the left has thus far not directly answered to the charge. While it may be tempting to disregard the right’s conspiracy as a paranoid fantasy, there is another option. The left can take advantage of it—by defining what it is fighting to replace, and what with.

This text is the first in a two-part essay series, which enters this ideological struggle from the left. As members of Not An Alternative (NAA), a collective that has spent the past eight years intervening within the sector for science and natural history museums in the United States under the generic name The Natural History Museum, our focus is on the disciplines and institutions broadly associated with natural history. What would it mean to replace the dominant tradition of natural history, which emerged from colonialism and enforces a capitalist relation to the world, and what might such a replacement open up for the left?

As part of this investigation, NAA is working with Indigenous and non-Indigenous theorists, historians, ethnobotanists, geographers, landscape architects, artists, and activists to define and organize around a counter-tradition of natural history, a Red Natural History, which sees the world not as a wealth of natural resources available for possession or profit, but as a world in common that cannot be enclosed. This first text situates this inquiry within NAA’s history of practice, telling the story of how we came to believe it is necessary to name and organize around an alternate tradition of natural history. The second delves into the question at hand, sketching out our collective’s provisional definition of Red Natural History.

The Museum Divide

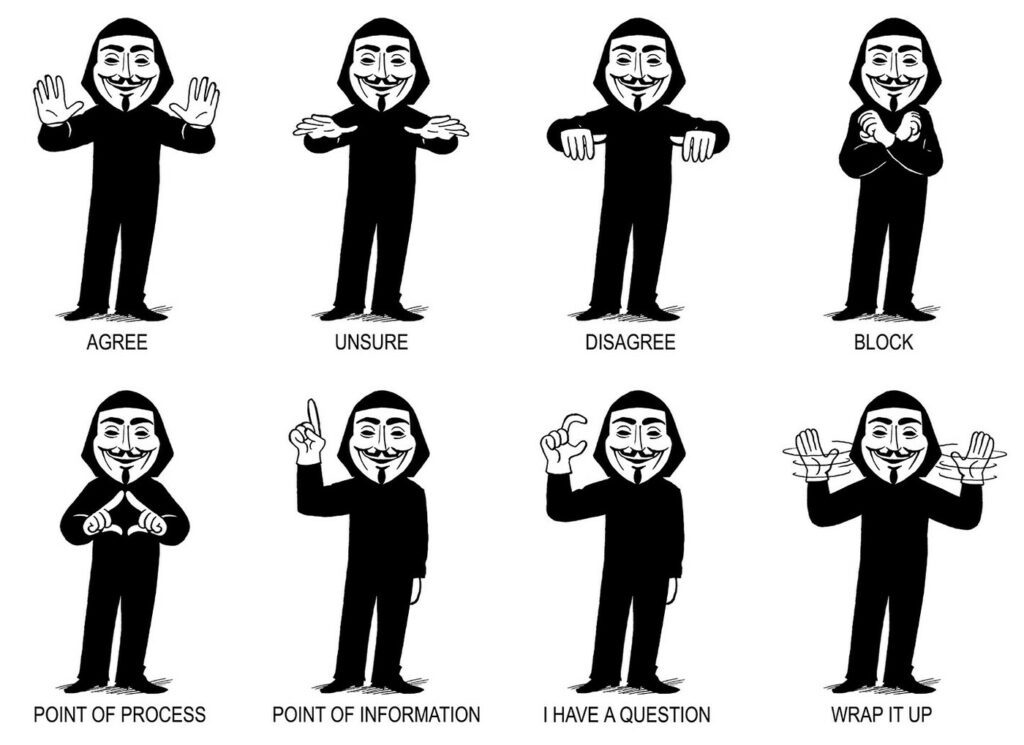

Established in 2004, NAA is a collective of artists, activists, and theorists with a mission to affect popular understandings of events, symbols, institutions, and history. We have worked shoulder to shoulder with homelessness and anti-eviction activists, Occupy Wall Street organizers, environmental justice advocates, climate scientists, and Indigenous organizers, engaging their struggles not through a typical head-on (or head-butt) approach, but through the occupation and redeployment of popular vernacular, symbols, and institutional forms. Our persistent goal, as much as aiming to challenge the right’s grip on power, has been to challenge the left to step into its own power. We have argued that without a strong organizational infrastructureand a language in common, left counterpower is very difficult to build and sustain. Without these resources, the left finds itself continuously starting from scratch, seemingly building from nothing other than the experience of co-optation and defeat.

As the right has spent billions of dollars seizing institutions for its ideological agenda—taking over the leadership of everything from public school boards to major museums—much of the radical left has abandoned such spaces, arguing that left counterpower should be built in the streets. For this camp, institutionality is assumed to be inherently conservative. In our collective’s analysis, this position has contributed to a strengthened and emboldened right, which has embedded itself within the concrete structures and infrastructures through which people learn to relate to the world, and a demoralized left, which tends to see its failures at the expense of what it has achieved.

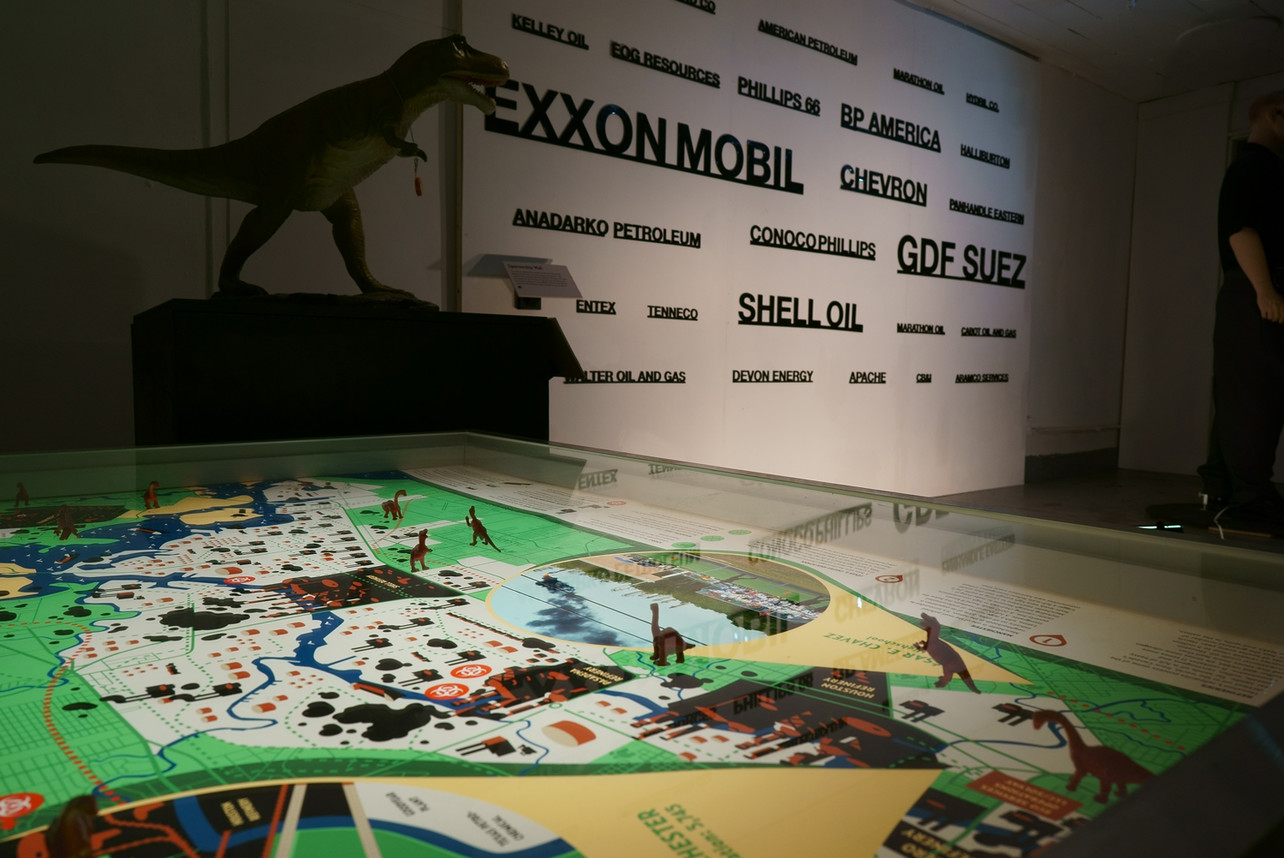

After a decade pushing for the development of a coherent visual language for the left—which NAA saw begin to coalesce, and then saw disappear, in our involvement with the eruption and disintegration of the Occupy movement—we founded The Natural History Museum (NHM), an experiment that aimed to model a left answer to the right’s institutional takeovers. The NHM was founded both as an intervention on the US sector for science and natural history museums and an institution in and of itself, an experiment in enlisting the museum as part of a communicative infrastructure for the climate and environmental justice movements. NAA’s hypothesis was that for museums to help pave the way towards a more just and sustainable future, they would need to not simply represent environmental injustice, but be rebuilt around the movements that are struggling against it.

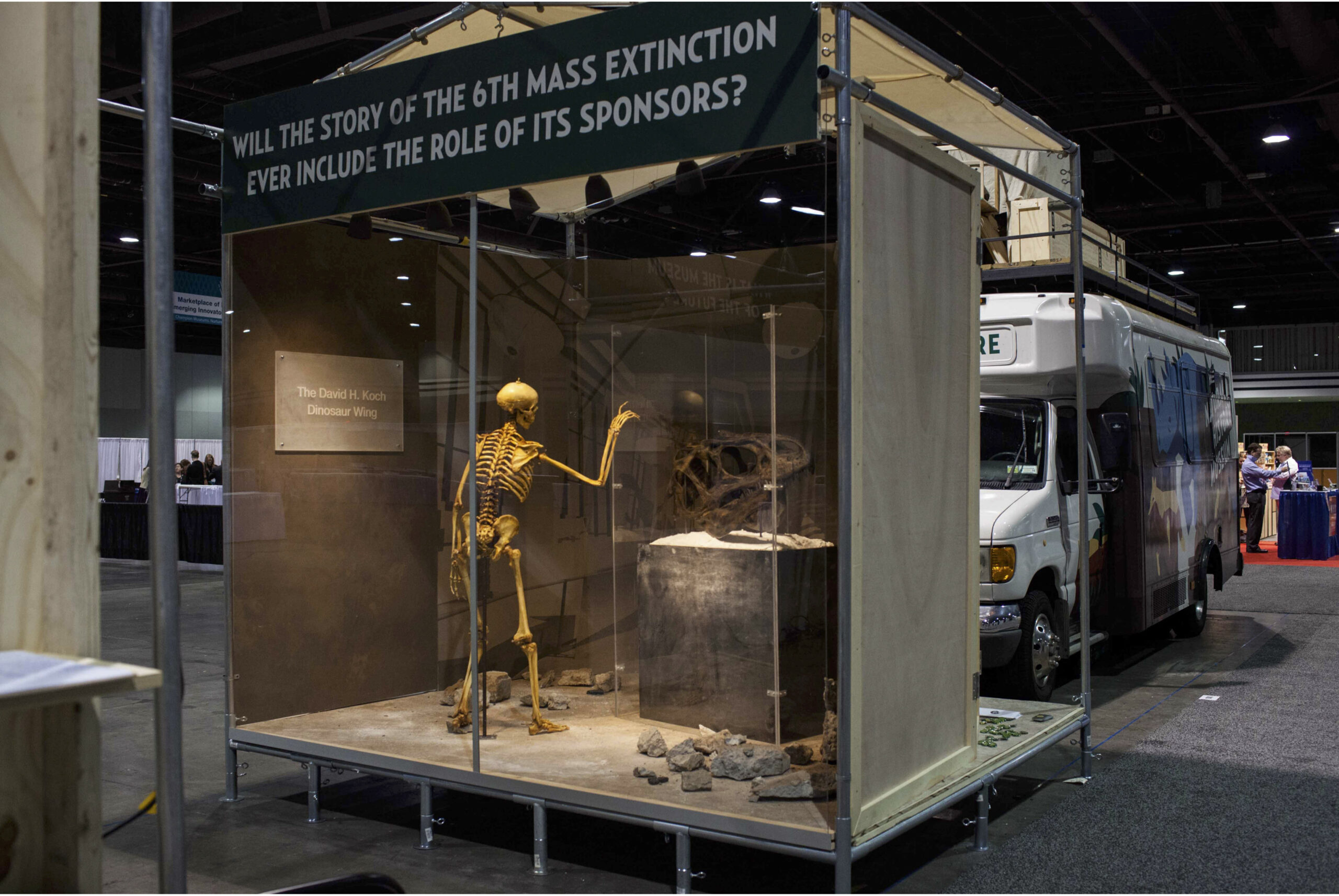

We started with a series of campaigns that aimed to split some of the country’s largest natural history museums from the industry interests they served. In the first of these campaigns, we enlisted dozens of the world’s top scientists and Nobel laureates to stand behind an open letter to the museum sector calling on all museums to cut ties with fossil fuel interests. We made a target of fossil fuel oligarch and climate science obfuscator David H. Koch, who for 23 years had held a position on the board of trustees of the American Museum of Natural History, one of the country’s largest natural history museums. Following dozens of news stories and more than 550,000 petition signatures, Koch quietly stepped down from his position at the AMNH—a monument toppled. Koch, in our calculus, was low hanging fruit, a symbolic target that could be leveraged to draw out comrades inside the museum sector with whom we could advance shared aims. In the Koch campaign, as well as other campaigns against corporate sponsors, fossil fuel investments, and right-wing funders of science denial, our aim was not to make museums like the AMNH better, but to activate an internal split—to reveal, in their internal contradictions, a kernel from which to build a left alternative.

Beyond the Museum

It was during the #NoDAPL movement at Standing Rock that our scope began to expand. When the Dakota Access Pipeline company bulldozed sites sacred to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, with the suspected aim of obliterating evidence of Traditional Cultural Properties before they could be officially designated by the federal government, it became evident that archeology, oral history, and other building blocks of “natural history” as it was conventionally understood could become crucial components of a pipeline struggle. Asked for support by Native Organizers Alliance, an Indigenous-led community organizing network, we leveraged relationships built over the previous two years to issue a public letter condemning the desecration, which was ultimately signed by more than 1400 archeologists, anthropologists, historians, and museum workers.

If our initial aim was to enter the struggle for environmental justice from the side, through the mediating apparatus of the museum, the conflict over archaeological and cultural resources at Standing Rock made it clear that some of the most consequential struggles over natural history were taking place not in museums, but on the land. Natural history was not just in the museum; it was also in the ground, standing as a bulwark against extraction.

Out of our collective’s long-term intervention within and beyond the natural history museum, we have come to the analysis that it is not the museum, but natural history itself, that needs to be split—a conceptual shift that allows for a radical reimagination of what institutional forms can best support collective emancipatory struggles. The museum is one apparatus that can be used to teach people to see the world in common that exists beyond and beneath the capitalist world, but there are others: Tribal Historic Preservation Offices, environmental justice think-tanks, progressive science associations, citizen science labs, journals like Society & Space, and so on.

Drawing a Red Line

Since 2017, NAA has been working primarily in solidarity and in collaboration with Indigenous communities in North America, most deeply with the House of Tears Carvers of the Lummi Nation. For more than a decade, the House of Tears Carvers has been carving totem poles, putting them on flatbed trailers, and bringing them to communities across North America to build alliances in the struggle to protect the land and water for the generations to come. The totem pole journeys visit Indigenous communities, farmers and ranchers, scientists, and faith-based communities, engaging groups in ceremonies led by Lummi elders. At each ceremony, participants are invited to touch the totem pole—to give it their prayers and power, and to receive its power in turn. The goal of the totem pole journeys is to connect communities on the frontlines of environmental struggle, and to build, through ceremony, a collective that did not previously exist—invoking generations past, present, and future. Lummi councilman Freddie Lane likened the totem poles to batteries: they are charged with the energy of those who touch them, and as they travel, they give the people energy in turn.

Our first projects with our Lummi comrades sought to leverage mainstream museums as communications infrastructures for their campaigns, which we experimented with in special exhibitions at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, the Florida Museum of Natural History, and the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. Our latest collaboration, the Red Road to DC, was a sort of exhibit that traveled across the land—a cross-country totem pole journey that aimed to support local communities’ efforts to protect sacred places threatened by dams, mining, and oil and gas extraction. The journey highlighted the critical importance of Tribal Nations in decisions on land, water and infrastructure projects, and demanded that the U.S. government respects the international legal standard of free, prior, and informed consent in its negotiations with Tribal Nations.

The Red Road to DC began at the Lummi Nation, where the tribe is fighting to protect the Salish Sea, orcas, and salmon from tanker traffic and pollution. From there, the pole traveled to Nez Perce territory in Idaho, where tribal leaders are fighting for the removal of four dams on the Lower Snake River, which have had devastating effects on the salmon, as well as the people who rely on fishing for their survival and sustenance. It then went to Bears Ears National Monument in Utah, which was opened to oil and gas extraction by the Trump Administration; and to the Greater Chaco region in New Mexico, where oil companies have been given permits to drill despite the area’s historic cultural importance to the Hopi, Navajo and Pueblo Nations. It then headed north to the sacred Black Hills in South Dakota, where Lakota activists are leading the #Landback campaign with a call to return Mount Rushmore to its original custodians; to the Missouri River and Standing Rock, where the struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline remains very much alive; to the rice fields of the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota, where water protectors are fighting to block the construction of the Line 3 Pipeline, which promises to transport nearly a million barrels of tar sands per day from Alberta to Wisconsin; and to Mackinaw City, Michigan, where the Bay Mills Indian Community has been fighting the existing Line 5 pipeline, as well as a plan to build a new pipeline tunnel under the Straits of Mackinac. At the end of the journey, the pole was received by Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland in Washington D.C. It was ultimately installed at the National Conservation Training Center where it stands as a symbol of Indigenous movements for life against extraction.

While the communities brought together through the totem pole journey are held in common by a shared history of settler-colonial dispossession, forced assimilation, and exploitation, the Red Road to DC foregrounded not the violent conditions they endure, but the sacred world they live to protect. Instead of drawing a black line between oil pipelines, colonial monuments, dams, and other monuments to extraction, the journey traced a red line between sacred sites, insisting on a relationship between people and place that cannot be seen from the capitalist point of view.

Our collective co-produced the Red Road to DC because we imagined it could model a response to the struggles over colonial monuments that have been erupting over the past several years, specifically by building power around a different kind of monument—one that reveals a way of seeing and relating to the world that is fundamentally irreconcilable with capitalism. Situated within a wider landscape of activist mobilization that includes struggles to change place names, to remove colonial monuments, to integrate anti-racist narratives into school curricula, to decolonize museums and repatriate stolen objects, and to return land to Tribal Nations, the Red Road to DC could be seen to be part of the Great Replacement that the right-wing conspiracists fear: a movement to destroy the myth of settler indigeneity that the United States was built on—of the “natural” right of the property-owning class of white settlers to the land and everything that can be extracted from it—and with it, the capitalist system that this myth enshrines.

For NAA, the Red Road to DC modeled a non-capitalist and anti-colonial practice of natural history, a natural history that gets its energy from the movements to support collective life and gives these movements energy in turn; a natural history that points to the world beyond capitalism and takes the side of the common. As a first step toward building out and organizing around this alternative, our collective has given it a name: Red Natural History.

Defining Red Natural History

After spending eight years organizing within and against the institutions of natural history, we are convinced of the need for a name that defines a partisan project of natural history—a name in common that can hold together the insurgent work of scientists, social scientists, conservationists, communities, and others who are struggling to transform the fields and disciplines broadly associated with natural history.

As we will elaborate in the next essay in this series, our collective defines “natural history” as the ever-unfolding history of life and land. While the dominant, institutionalized tradition of natural history is informed by a colonial logic of extraction, enclosure, and exploitation, we argue that there is another tradition of natural history, built not on colonial or capitalist relations, but on a comradely and reciprocal relation to land, life, and labor.

For us, the “Red” of Red Natural History does not only suggest a relationship to the history of Indigenous struggle, but also to the “red threat” that terrifies the right, the red flags that have been waived by revolutionaries around the world for centuries, and the red alerts issued by climate scientists to warn of the storms to come. In our interpretation, Red Natural History is not just a proposal for charting alternate histories of natural history, but also for embracing the right’s fantasy of left power. It is also a call for the left to search for the ancestors, irrespective of their identities, whose emancipatory struggles live on in the contemporary movements to remake the world as a world in common.

Our collective’s perspective on Red Natural History is one of many that will be shared over the next year, as we have been working with Indigenous and non-Indigenous scientists, scholars, and practitioners to publish a dossier of speculative essays that give meaning to the term. The point of this collaborative investigation is not to reach consensus, but to create energy around the term Red Natural History, to signal a gravitational pull from the critique of the imperialist tradition of natural history to the positive articulation of another—a tradition of natural history that can rise to the challenges of today’s overlapping and intensifying social, climate, and extinction emergencies.

Our hope is that Red Natural History does not remain an abstract concept, but that it has an effect on practice—that it provides a framework that insurgents from fields associated with natural history (including archaeology, anthropology, geography, history, ecology, and so on) can use to articulate what they share in common as they struggle to leverage their institutions’ resources to support the communities that are leading efforts to protect natural and cultural heritage, block extractivist projects, and point the way to a just and livable future for all.

Not An Alternative (est. 2004) is a collective that works at the intersection of art, activism, and theory. The collective’s latest, ongoing project is The Natural History Museum (2014–), a traveling museum that highlights the socio-political forces that shape nature. The Natural History Museum collaborates with Indigenous communities, environmental justice organizations, scientists, and museum workers to create new narratives about our shared history and future, with the goal of educating the public, influencing public opinion, and inspiring collective action.