Ashley Dawson is a professor of Postcolonial Studies at the City University of New York, who has spent two decades developing a cogent diagnosis of the contemporary climate, environmental, and biodiversity crisis. His research and public writing charts how European colonialism has decimated people all around the planet over the last 500 years, as well as how people have worked together to fight back. In this interview with The Natural History Museum’s Steve Lyons, Dawson unravels the tangled histories of colonialism and fossil capitalism, considering how corporations, states, and conservation organizations have worked together to re-colonize the formerly colonized world, supercharging the rapid loss of biodiversity in the Global South. He also explores some of the traditions of resistance from which non-capitalist modes of life have been and can be built, arguing that Indigenous sovereignty and #landback must be at the center of our collective response to converging crises of our era.

Steve Lyons Several of your most recent works, including both Decolonize Conservation and Environmentalism from Below, raise the problem of what you and others call “fortress conservation,” which can be seen in so-called “nature-based solutions” to climate change. Could you explain how nature-based solutions like the “30×30” campaign pitch themselves as positive responses to the climate crisis—but also, what do they promise to do from the perspective of people living in the Global South? What is new about these proposals, and what have we seen a million times before?

Ashley Dawson To take a step back, we need to understand that although the lion’s share of attention around environmental issues today falls on the climate crisis and increasing carbon emissions, this is not simply a climate crisis. We’re facing what I call an intersectional crisis that has many different facets that are unfolding alongside one another. One of the other crucial elements is a crisis in biodiversity.

In 2016, I published a book called Extinction: A Radical History, which shows how the capitalist system and its colonial pre-history are linked to a massive extinction of species around the planet. This extinction event has been happening for hundreds of years, but it’s been gathering pace over the last 50 years, where we’ve seen a huge die-off that has been linked to habitat destruction around the world.

This is the context out of which many of the big conservation organizations, almost all of which are headquartered in the US, have started talking about “nature-based solutions” to the crisis of the environment. When conservation organizations bring up nature-based solutions, they’re talking about this kind of intersectional crisis that we’re seeing happen right now: on the one hand, the increasing rate of extinction (not just of specific species, but whole ecosystems), and on the other hand, the climate crisis.

On its surface, “nature-based solutions” is an attractive idea. The idea is that if we start factoring in the contribution that nature makes to human survival and prosperity, we will see how nature can provide a solution to the environmental crises of the current moment. In practice, a toxic system has been created under the banner of “nature-based solutions,” which allows polluting corporations to pay the governments of countries that have abundant forests and other natural ecosystems that could theoretically absorb the carbon that these companies continue to emit. This is the idea of carbon offsetting.

If you have a system of carbon offsets, you can value those offsets, and then you can trade them like commodities, bonds, or any other capitalist financial instrument. This is what is happening now: corporations that continue to pollute the planet are figuring out ways to keep polluting, all the while convincing the international community that they’re “carbon neutral.” A “carbon neutral” company is simply one whose continued emissions are offset by its purchases of these carbon offsets.

Out of this situation, over the last ten years or so, big conservation organizations based in the wealthy, core capitalist countries have discovered that they can make a lot of money by setting aside land in different parts of the world in order to generate carbon offsets. Organizations like the World Wildlife Fund are working to get in on the aggressive financialization of nature that was ushered in by carbon offsetting.

As you suggested, there’s a problem with all of this, even though it sounds like a win-win solution for everyone: you make polluting corporations pay, and they help people by paying for ecosystems to remain in place. The problem is that in most cases, it turns out these areas that are being set aside as sites of offsetting don’t absorb very much carbon. There was a recent report that said that 90% of the officially accredited carbon offsetting schemes in the world’s rainforests aren’t doing anything other than generating a lot of capital for conservation organizations and financial speculators in green capitalism. The climate crisis is actually intensifying. The biodiversity crisis is intensifying. And Indigenous peoples around the world who live in these new “protected areas” are being dispossessed of their lands.

How is this even possible? Many Indigenous communities around the world have customary title to land, but do not have the kinds of property agreements and contracts that Western legal systems recognize. This means that when corrupt government officials decide to designate an area as a “protected area,” they can just kick out the Indigenous Peoples who have been stewarding that land for thousands and thousands of years. Once the Indigenous Peoples are dispossessed of their land, there is nobody left to defend that land and to protect it from extractive industries. So, when a protected area is set up in a Global South country, you will often find that the country will also grant concessions to European or North American timber companies, mining operations or fossil fuel corporations, which will immediately come in and start extraction on that land.

So, the problem with “nature-based” schemes is not even simply that they are bad at reducing carbon emissions. They’re also fueling more carbon pollution in the Global North and more extractivism and carbon pollution in the Global South, thus accelerating biodiversity loss. They are also deluding the public into thinking that we’re solving the environmental crisis.

We need to organize against this. This means helping Indigenous people on the ground who are fighting these kinds of “protected area” designations. It also means getting the word out, in core capitalist countries like the US, about what is happening under the veil of “nature-based solutions” and carbon offsets.

SL Your recent co-edited book Decolonize Conservation is not only unveiling the problems you’re raising here. It is also exploring alternatives. What does conservation look like when it’s being decolonized? What might it look like when, for example, the big green conservation groups have been abolished and there’s a completely different understanding of what it means to protect the world we share in common?

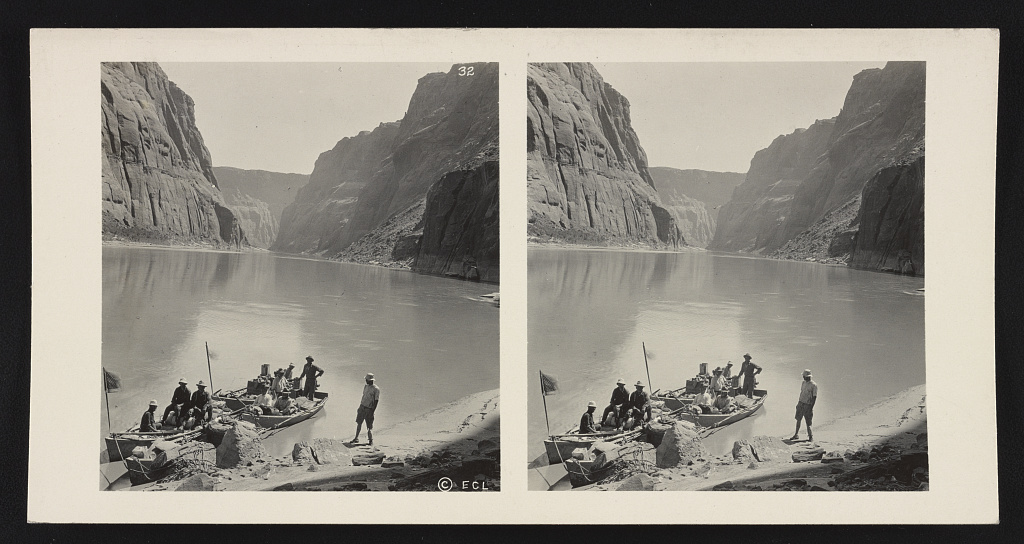

AD The point of the Decolonize Conservation collection is to focus people’s understanding on the way that the big conservation organizations are using “protected area” designations to dispossess and displace people, and to historically situate this colonial dynamic within conservation. With the establishment of National Parks in the late 19th and early 20th century, the United States is famous for introducing what we call the “fortress conservation” paradigm of wilderness conservation. In the process of establishing the Parks system, Indigenous peoples were forcibly displaced from their homelands, and areas of land were enclosed and protected as examples of untouched wilderness. But just beyond their borders, the spoliation continued unabated. This “fortress” model of conservation was an experiment in creating a kind of vacuum-sealed natural space that would supposedly remain completely pristine without any human intervention.

Environmental science has shown that this approach to conservation doesn’t work. When you attempt to seal off a relatively small space—even one as large as a National Park, biodiversity will gradually become impoverished. Without the external inputs you get in a healthily-functioning ecosystem, the ecosystem will begin to wind down. Fortress conservation is not viable in human terms, because it’s dependent on genocide. But it is also not viable in ecological terms.

With Decolonize Conservation, I worked with comrades at Survival International to circulate a series of talks and reports given by Indigenous activists and allies from around the world, which together make a case for how the new ideas of “nature-based solutions” are simply a fresh way of packaging the project of fortress conservation, which has been in place for the last 100 years or so, but with much higher stakes, because as we know, the planet is in immense crisis.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature, among others, has been proposing that 30% of the planet’s surface should be designated as Protected Areas by 2030. Right now, about 17% of the planet is set aside. Some of the new Protected Areas will be coastal ocean areas that are not inhabited in a regular way by human beings, but even these areas are used by fisherfolk, whose livelihoods are going to be threatened as a consequence. More consequentially, a significant portion of the new Protected Areas will be on land occupied by Indigenous peoples. This is why we argue that 30×30 is massive neo-colonial land grab.

What would an alternative look like? What my collaborators at Survival International and I argue is that the alternative to fortress conservation is indigenous sovereignty—land back. Scientists have shown that even though Indigenous Peoples comprise only about 5% of the world’s population, they are stewards on their remaining lands of 80% of the world’s biodiversity. We need to recognize Indigenous sovereignty in places where it’s not recognized, which unfortunately is most of the planet, including the formally designated “Protected Areas” where Indigenous Peoples have traditionally lived.

Underlying all of this, we also need to shut down polluting industries in the Global North, because this whole system of conservation and nature-based solutions is totally unsustainable. You can’t set aside 30% of the planet or even 70% of the planet, if the other 70% or 30% is a site of rampant capitalist exploitation and pollution. Even on a commonsense level, it’s ridiculous to assume that you can kind of put up fences and protect some part of the planet against the rampant extractivism and destruction happening everywhere else. We need to have respect for Indigenous sovereignty. We need to fight for land back. And we also need to shut down the rampantly extractive capitalist system that dominates the planet right now.

SL In your newest book, you argue that “environmentalism from below” is “animated by struggles for collective control of the environment and social commons in the face of global environmental degradation and dispossession carried out by neocolonial extractivist capitalism.” I’m interested in probing this question of collective control, which in the context of Indigenous struggle in the United States, often rides on the question of Tribal sovereignty, which you’ve already raised. How should we think through the potential contradictions between, on the one hand, the urgent political necessity to respect the sovereignty of Indigenous Nations and, on the other hand, a normative environmentalist vision for how the world—from the land to the atmosphere—ought to be respected as a world in common. As we know, these things are not necessarily aligned. We could think of Bolivia’s investments in fossil fuels or the Navajo Nation’s commitment to coal, as Andrew Curley discusses in his new book Carbon Sovereignty. How should we think through, navigate, and politically engage these contradictions when they emerge?

AD This is a hugely important question. Among white environmentalists, there is often a kind of unvarnished, uncomplicated celebration of Native environmentalism, eliding the fissures and complexities within Indigenous cultures and homogenizing incredibly heterogeneous cultures all around the planet. Having acknowledged that there’s not only heterogeneity within Indigenous cultures, but also political fissures and conflicts between and among them, I think it’s important to remind ourselves that there are traditions of resistance to the dominant colonialist capitalist framework, traditions which help us reconsider how humans are in relationship with the natural world.

In his Two Treatises of Government, the English philosopher John Locke famously argues that God wants the world to be turned into a garden and flourish, which meant that the settler-colonial Europeans were doing God’s work when they occupied land, brought their agricultural techniques to bear on it, and dispossessed Indigenous people who were supposedly leaving it undeveloped. Locke’s argument was that by mixing their labor with the land, settlers had a right to the land. It was a case in which, as Robert Nichols has recently argued, theft became property.

The Indigenous cultures the settler-colonists displaced often had completely different attitudes towards the land—understandings of mutual reciprocity and responsibility between human cultures and the rest of the natural world, as well as collective forms of governance that enshrined these reciprocal relations to the land. These non-capitalist ways of relating to the land haven’t disappeared. In my work around the climate crisis and environmental crisis over the past fifteen years, I have been inspired by groups like the Indigenous Environmental Network, which has been making arguments about the importance of Indigenous worldviews in resisting all of the forms of dispossession that we are talking about, including those pursued in the name of carbon offsets.

At the moment, in one of my classes I am teaching the testimonial of Rigoberta Menchu, a Mayan woman from Guatemala, who was part of the Indigenous resistance to the US-backed genocidal regime in Guatemala in the 1980s. Menchu talks about how the government sent troops into Mayan villages to violently take their land and crush their resistance. Many of these troops were Indigenous. The government found ways to recruit Indigenous people out of their communities, train them and turn them into foot-soldiers for its genocidal project against Indigenous people, which was also an effort to take Indigenous land away and occupy it for cotton or coffee plantations.

How do we relate to those kinds of bloody histories? For me, it’s important to listen to people on the ground to understand their struggles and to figure out how, as someone with a settler history, I can meaningfully build solidarity with people who are trying to defend their claims to the land and to resist extractivism in all its forms. While Indigenous People may have taken the lead in fighting fake fixes like carbon offsetting, all of us have a stake in this struggle for our collective future.

SL In your new book, you write that we can learn from the oppressed people of the world who are “most vulnerable to—but also least responsible for—the climate crisis,” but who “also happen to be people who have not been wholly divorced by the capitalist system from sustainable ways of living and worldviews that makes such balanced lives possible.” Where do we see this non-capitalist alternative in the world today? What does it look like to organize around it? Why is it important to see practices and worldviews that have not been entirely captured by capitalism? And how can we do so without resorting to a kind of “primitivist” imaginary—locating the future in the past.

AD What I’m trying to emphasize in my book is that capitalism operates on a set of moving, roving frontiers, and some of the key frontiers for global extraction and destruction are in former colonized countries in the global South, which happens to be where the climate and environmental crisis is manifesting itself, both earliest and most severely. However, this constantly expanding colonial capitalist frontier is also a site where practices of resistance to extraction and dispossession are constantly being developed.

I think you’re right to resist the kind of “salvage” orientation that has characterized anthropology and ethnography in relation to Indigenous Peoples. For most of the 20th century, anthropologists would go into communities in the non-Western world with the assumption that the lifeways of the people they encountered were on the brink of extinction, believing that they needed to record as much as possible about these people’s lives, customs, and cultural traits before they were mowed down by modernity and development. Resistance to this epistemological orientation towards Indigenous cultures is important because, as many Indigenous people point out, despite centuries and centuries of genocide, Indigenous people are still here, resisting and fighting back at the forefront of movements resisting colonialism and capitalism. People at the cutting edge of exploitation and extractivism are constantly finding ways to connect with the cultures that their ancestors created and passed down, recreating them in novel situations.

There is an immense diversity of forms of struggle to protect the global environmental commons, particularly in the Global South. We need to support those forms in all of their heterogeneous variety, because, frankly, we’re not currently winning the fight against the environmental crisis. And even if we could stop carbon emissions today, there is so much locked in already. A lot of what we take for granted as “civilized people” in the Western world and in much of the rest of the planet since the Neolithic Revolution, when a certain form of agriculture and cities and civilization was created, will transform within our own lifetime because of the carbon already in the atmosphere. We need to be thinking about forms of environmentalism from below that are going to be able to carry humanity through these coming massive convulsions and transformations.

SL You’ve joined us as a Red Natural History Fellow to think with us about “red natural history.” In my mind, “ren natural history” names the alternative to the colonial tradition of natural history, which you’ve raised several times in this conversation. What is red natural history, for you. What does it make possible, either as a concept or as a name for a cluster of practices ? What does it demand of our institutions of natural history? Where are you seeing it active in the world? And lastly, how can red natural history contribute to your vision for Ecological Reconstruction, which, as you point out in Environmentalism from Below, must be anti-capitalist, feminist and decolonial?

AD I’ve talked at length now about how important respecting Indigenous sovereignty is to maintaining biodiversity. On one level, I would say if we want to talk about what red natural history is, we need to look into traditions of Indigenous ecological stewardship in more detail. There is some good recent work in this vein: for example, Melissa K. Nelson and Dan Shilling’s essay collection Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Dina Gilio-Whitaker’s As Long as Grass Grows, as well as more popular accounts of Indigenous knowledge and ecological practices like Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass and Jessica Hernandez’s Fresh Banana Leaves. But overall I would say that there’s a lot more work to do to understand what we’re here calling Red Natural History.

This is not entirely surprising, because there are relatively few places on the planet where Indigenous people actually have sovereignty over their land. Exploring concepts like Buen Vivir, which comes out of Indigenous movements in the Pink Tide countries of Latin America, and seriously engaging the philosophies and practices that undergird these concepts, ought to be a key element of red natural history as it develops.

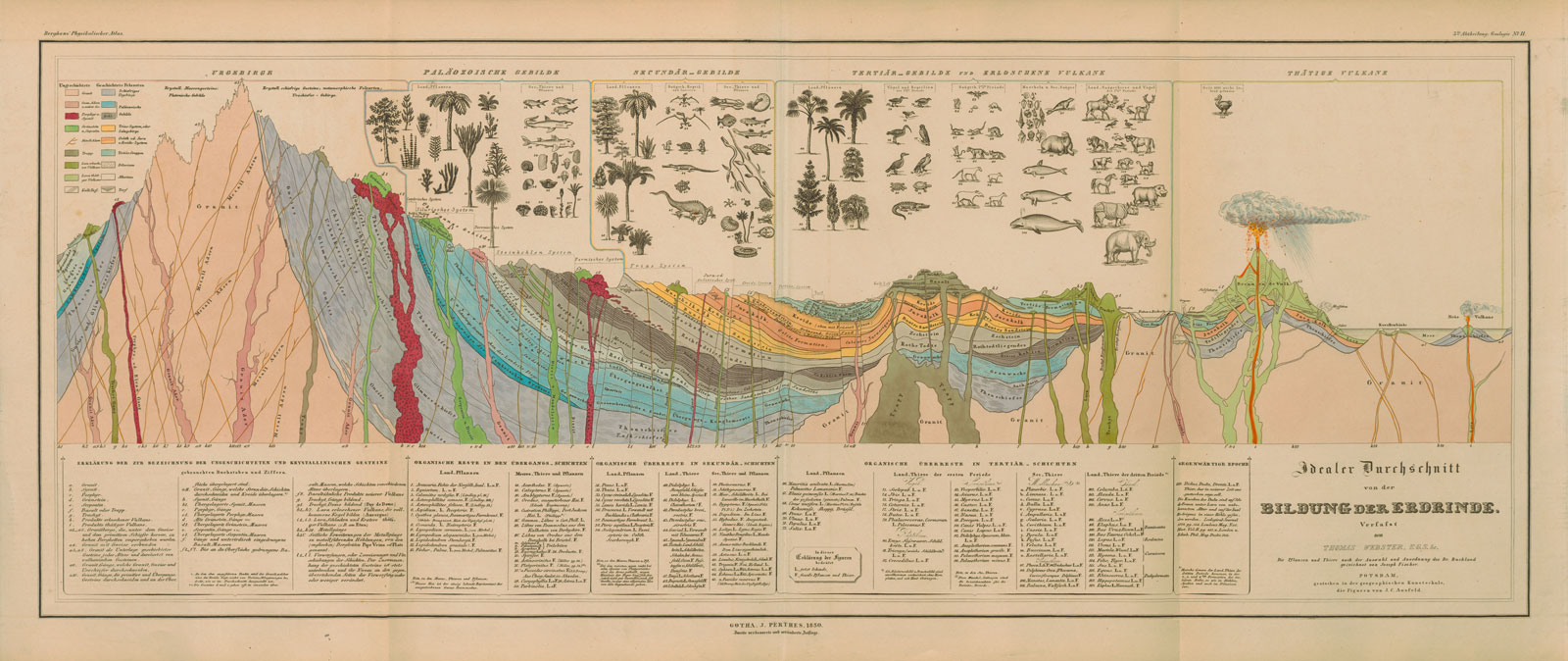

In addition, though, I think it’s important to see that there have always been contestations to the dominant tradition of natural history. In my Social Text essay on “red natural history,” I discuss the challenge to Darwinian thought that was articulated by Peter Kropotkin, who was an anarchist and a geographer. Darwin famously argued that evolution happens through a process of natural selection—in other words, competition, not just between species, but between individuals in a species—essentially taking the 19th century English capitalist world that he inhabited and exporting it to his analysis of evolutionary biology. By contrast, Kropotkin drew on his observations of natural ecosystems and species in the rugged conditions of Siberia to argue that, when one looks at the natural world within species boundaries, we don’t see competition as much as what Kropotkin famously calls “mutual aid.”

We need to recuperate dissenting radical traditions within natural history, which, like Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid, can offer counter-histories to the imperial discourses of natural history. If we can crack open the history and the discourses, hopefully we can also open up the dominant institutions and mobilize them within our struggles. Institutions like natural history museums can be sites for dissenting traditions, whether these traditions come from scientific observers and curators within the museum or from environmental movements outside the museum.

I think that we need to have movements that cultivate dual power—movements that build power both through institutions and beyond them. Natural history’s institutions have serious structural constraints, and the project of working inside and outside at the same time is not an easy one. Working inside the institutions can drain power away from efforts to create autonomous alternative forms of environmentalism from below. But at the same time, we cannot simply walk away from important sites of public power and public culture, like natural history museums. We need to try to break them, transform them, and refashion them as movement resources.

Ashley Dawson is professor of postcolonial studies in the English department at the Graduate Center, City University of New York and the College of Staten Island. His latest books include Environmentalism from Below: How Global People’s Movements Are Leading the Fight for Our Planet (Haymarket, 2024), Decolonize Conservation: Global Voices for Indigenous Self-Determination, Land, and a World in Common (Common Notions, 2023), People’s Power: Reclaiming the Energy Commons (O/R, 2020), Extreme Cities: The Peril and Promise of Urban Life in the Age of Climate Change (Verso, 2017), and Extinction: A Radical History (O/R, 2016). A member of the Social Text Collective and the founder of the Public Power Observatory, he is a long-time climate justice activist.

Ashley Dawson is professor of postcolonial studies in the English department at the Graduate Center, City University of New York and the College of Staten Island. His latest books include Environmentalism from Below: How Global People’s Movements Are Leading the Fight for Our Planet (Haymarket, 2024), Decolonize Conservation: Global Voices for Indigenous Self-Determination, Land, and a World in Common (Common Notions, 2023), People’s Power: Reclaiming the Energy Commons (O/R, 2020), Extreme Cities: The Peril and Promise of Urban Life in the Age of Climate Change (Verso, 2017), and Extinction: A Radical History (O/R, 2016). A member of the Social Text Collective and the founder of the Public Power Observatory, he is a long-time climate justice activist.

Kai Bosworth

Kai Bosworth

Andrew Curley (Diné) is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geography, Development, and Environment at the University of Arizona and a 2023-25 Red Natural History Fellow. His research focuses on the everyday incorporation of Indigenous nations into colonial economies. Building on ethnographic research, his publications speak to how Indigenous communities understand coal, energy, land, water, infrastructure, and development in an era of energy transition and climate change. Curley’s first book Carbon Sovereignty: Coal, Development, and Energy Transition in the Navajo Nation (University of Arizona Press) came out in 2023.

Andrew Curley (Diné) is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geography, Development, and Environment at the University of Arizona and a 2023-25 Red Natural History Fellow. His research focuses on the everyday incorporation of Indigenous nations into colonial economies. Building on ethnographic research, his publications speak to how Indigenous communities understand coal, energy, land, water, infrastructure, and development in an era of energy transition and climate change. Curley’s first book Carbon Sovereignty: Coal, Development, and Energy Transition in the Navajo Nation (University of Arizona Press) came out in 2023.