The brutal police killing of George Floyd earlier this year spurred uprisings in cities across the US. These uprisings came in the form of highway blockades, port shutdowns, unsanctioned monument removals, torched cop cars, and Minneapolis’s Third Police Precinct being burned to the ground. While this was happening, congressional Democrats took a knee; the street in front of the White House was renamed Black Lives Matter Plaza; letters of “solidarity” from universities, museums, major corporations, and small businesses cluttered the web. Looking back at the slowing energy around the Black Lives Matter movements during the fall, we can see a pattern that is common to so many contemporary movements: a shift from popular revolt to corporate takeover.

Corporations’ and mainstream liberals’ widespread use of BLM’s hashtags, chants, and symbolic rituals led to a flood of media arguing that the movement’s symbols had become its Achilles heel.[1] This genre of writing is a mainstay of left criticism. It tends to draw a sharp distinction between two ways of practicing politics: one that prioritizes direct material intervention as the basis for revolutionary change, and another that wagers on the political efficacy of symbols—repeatable acts, slogans, images, and other forms of action that connect the people who use them to the abstract idea of a specific movement. Critics argue that there are at least two problems with the symbolic approach to activism. First, when deployed by the left, symbols don’t lead to material transformation. Performances often make those of us on the left feel like we’re changing the world, but they mainly function to divert our energy from the real work of transforming the material conditions of oppression. Second, our symbols leave our movements vulnerable to infiltration and subversion by capitalists, who can easily seize and redirect them. Once the capitalists use our symbols, not only do those symbols lose their capacity to challenge power, but they no longer even belong to us.

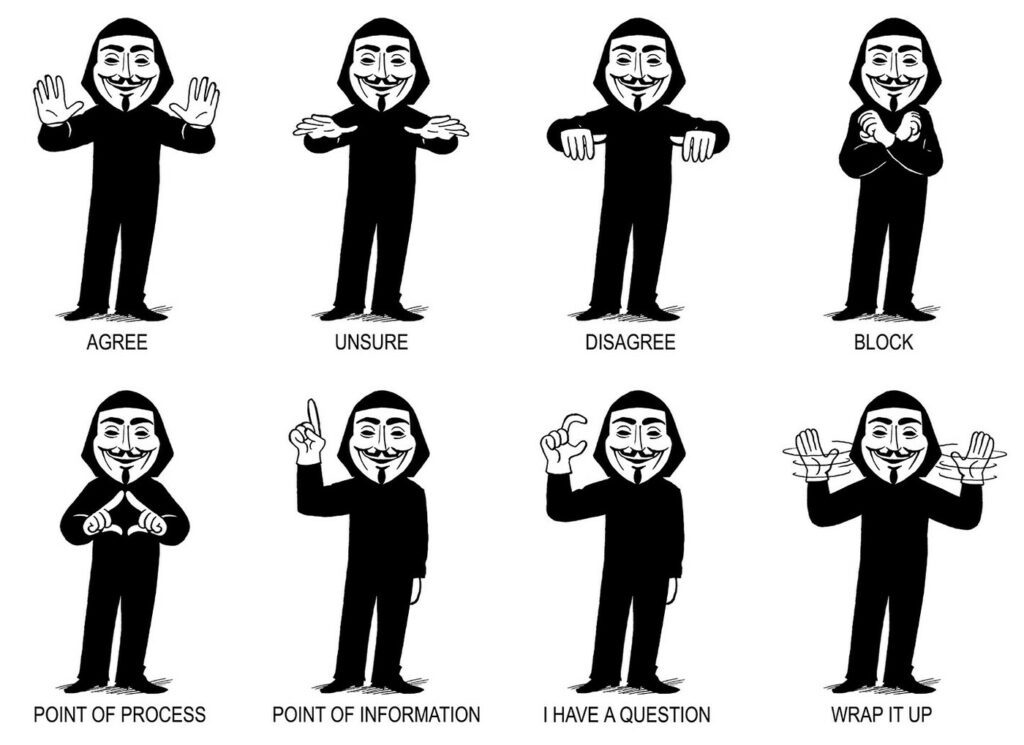

From an anti-symbolic position, we recognize that our symbols are efficient only when used against us: as means of quelling militancy, sowing internal divisions, and producing an illusory image of “resistance” in the absence of revolutionary organization. At the same time, few have trouble seeing how the symbols of white supremacy are a key source of power for the right. Critics obsessively track the symbols, subcultures, and dog whistles of white supremacist belonging, amplifying their efficiency in the process. Beyond the Confederate flag, white nationalists have absorbed into their symbolic lexicon the green frog, the ubiquitous hipster-Nazi haircut, the Hawaiian shirt, and the “OK” hand signal. Many of us use our social media feeds to broadcast these findings, acting as though our most urgent challenge is to find the best proof that fascism has arrived. We see signs of fascism everywhere, even including where they are not. But we are often blind to the symbols, rituals, and modes of communication through which left counterpower is built.

Into this context, this text introduces a keyword, the language in common, which allows us to see how the left communicates the collective power it builds. The language in common is not merely the constellation of symbols, hashtags, and performative tactics mobilized in the context of social movements. It is the mode of communication of a revolutionary collective coming into being. Collective movements are not fixed entities that precede their modes of appearance. They are constituted as they are made visible and audible. The repetition of images, rituals, and signs builds and expresses collective power as it inscribes a gap through which noncapitalist modes of belonging appear. In this process, language becomes a material force as it voices an alternate imagination of the world.

To be clear, this text does not advocate for the continued use of specific symbols, hashtags, and performative tactics. Nor does it take an uncritical position on their expropriation. Instead, it aims to advance a framework that refuses the either/or debate about material versus symbolic tactics by prioritizing the productive feedback loops between them. The language in common subordinates the question of political tactics to the question of political side-taking, insisting that the operative division is not between the material and the symbolic, but between us and them.

But who is “us”? Against the “we-skepticism” that has pervaded academic leftism in Europe , the UK, and North America, this text is unapologetic in its use of “we” and “us.”[2] The signifier “we” constitutes a central and irreplaceable component of the left’s language in common. It does not invoke a specific empirical referent (a subject that exists), but rather the imaginary subject of our politics (a subject that insists). To speak in the “we” is not to speak for others, but to posit a collective subject that can be struggled over. The same is true of the term “the left” as it is used in this text. There is no question that the left is internally divided. As a collectivizing term, the “left” casts a wide net over Molotov-cocktail-wielding anti-fascists and well-meaning liberals, community organizers and insurgent politicians, anarchists and communists, reformists and abolitionists. Its connotations are different depending on who is speaking and to whom. This text refers to the left in its widest sense: to delineate those who take the side of the common. The point is not to fixate on what fragments us from within, but instead to combat left fragmentation—starting by committing to the codes that signify our collective difference. By attuning our gaze to the language in common, we expose the terrain on which our collectivity is built, sustained, and defended. This terrain is not a space of agreement or consensus. It is a gap—an open space of struggle in which to determine our collective horizon.

Building the Language in Common

Capitalism is, of course, a system of production, circulation, exploitation, and extraction. As it expands, it sets the coordinates through which we experience and engage in the world, producing a depressive realism that strangles our collective imagination. The power of capitalist realism, as Mark Fisher theorizes it, is in its capacity to convince us that capitalism has mapped the world so completely that we cannot imagine an alternative. It achieves this feat by laying claim to the symbolic systems through which we express ourselves, define our position, and establish the horizon for our politics.[3] We are trained to see land as property, monuments as testaments to the victory of the oppressor, and workplaces as monoliths synonymous with the boss. Alienated from the capitalist world, we reach for the tools of critique. We are neither the landlord, nor the oppressor, nor the boss. Our negative attachment to the system of oppression keeps us on our heels, firmly in enemy territory. We write it off, cede the ground, and are left with no affirmative place to stand.

Capitalist realism conscripts our desires to the capitalist world, but it also blinds us to the presence of actually existing alternatives to capitalism—modes of life and ways of seeing that do not fit on the capitalist map. Strands of Marxist feminism and Indigenous Marxism have worked against this tendency by insisting on the noncapitalist remainder in the capitalist world. Building on David Harvey’s reading of Rosa Luxemburg, thinkers such as Sylvia Federici and Glen Sean Coulthard take specific aim at Marx’s theory of primitive accumulation, which holds that the brutal transfer of noncapitalist forms into capitalist ones was a transitional phase in the development of capitalism. Coulthard argues that primitive accumulation should not be understood as a stage in the transition to capitalism, but rather an ongoing process of dispossession. This process is felt most violently by Indigenous communities who have already been dispossessed of their lands and ways of life, but who also, through their own strength and fortitude, continue to hold land as sacred and inalienable.[4] One implication of this critique is that there remain elements of noncapitalist life—unceded lands, modes of life, and ways of seeing—that remain beyond the grip of capitalism. There is a gap in the capitalist world—hard-wrangled by people who continue to refuse forced assimilation by the settler-colonial state—from which a language of difference has been and can be built.

While the left has spent the past fifty years caught in a circuit of invention and abandonment, building effective modes of communication only to disavow them at the first sign of co-optation, Indigenous Nations have struggled for their languages and cultural traditions despite targeted campaigns to erase, outlaw, or assimilate them. Through a centuries-long commitment to tradition, Indigenous Nations in so-called North America have been able to recognize their commonality, make visible their fundamental irreconcilability with the extractivist logic of capitalism, withstand state-sanctioned extermination campaigns, and mobilize their collective power to build solidarity, block pipelines, and protect water and land. These are lessons from which the non-Indigenous left must learn.

Nick Estes develops the concept of the “tradition of resistance” to theorize how, from the perspective of the Oceti Sakowin Oyate, or Great Sioux Nation, every Indigenous struggle for liberation is built upon the one that preceded it. Not only have Indigenous communities been struggling against the same system of settler-colonial dispossession for centuries. These communities also understand the ways in which the power they build in the present has been derived from the same sources for generations. The rituals, cultural practices, and political tactics devised by those who struggle over a place operate in fidelity with ancestral teachings. “By drawing upon earlier struggles and incorporating elements of them into their own experience,” Estes writes in a recent book on Indigenous resistance, “each generation continues to build dynamic and vital traditions of resistance. Such collective experiences build up over time and are grounded in specific Indigenous territories and nations.”[5] Rituals, symbols, and other cultural practices are not abandoned, in other words. They are reawakened, transformed, and expanded.

This attitude toward tradition is alien to much of the North American, European, and UK left. Leftist organizers, activists, and theorists hunt for the next viral hashtags, drive attention toward them, and mobilize energy around them, with the full expectation that they will only be useful in holding popular attention for a moment before fading into oblivion. Before hashtags, there were “mindbombs.” In the mid-1970s, this is what Greenpeace founder Bob Hunter famously called images that could inspire collective action.[6] When approached from the perspective of media strategy, the images, rituals, and signs of counterpower have a shelf life. They are empty signifiers: equivalent, interchangeable, and competing amongst themselves within an economy of attention. When they lose their impact, they can be discarded and replaced.

If the images, rituals, and signs of collective power are not approached from the perspective of marketing and public relations, it becomes possible to understand and treat them differently—not as empty signifiers that behind-the-scenes strategists can control, but as the byproducts of the collectives who pick them up, use them, and transform them in the process of building counterpower. When we refuse to see the images, rituals, and signs we organize around as isolated one-offs, we can begin to build continuity between our struggles. We can recognize how our symbols contribute to a language in common that sets the coordinates for how we understand and relate to the world.

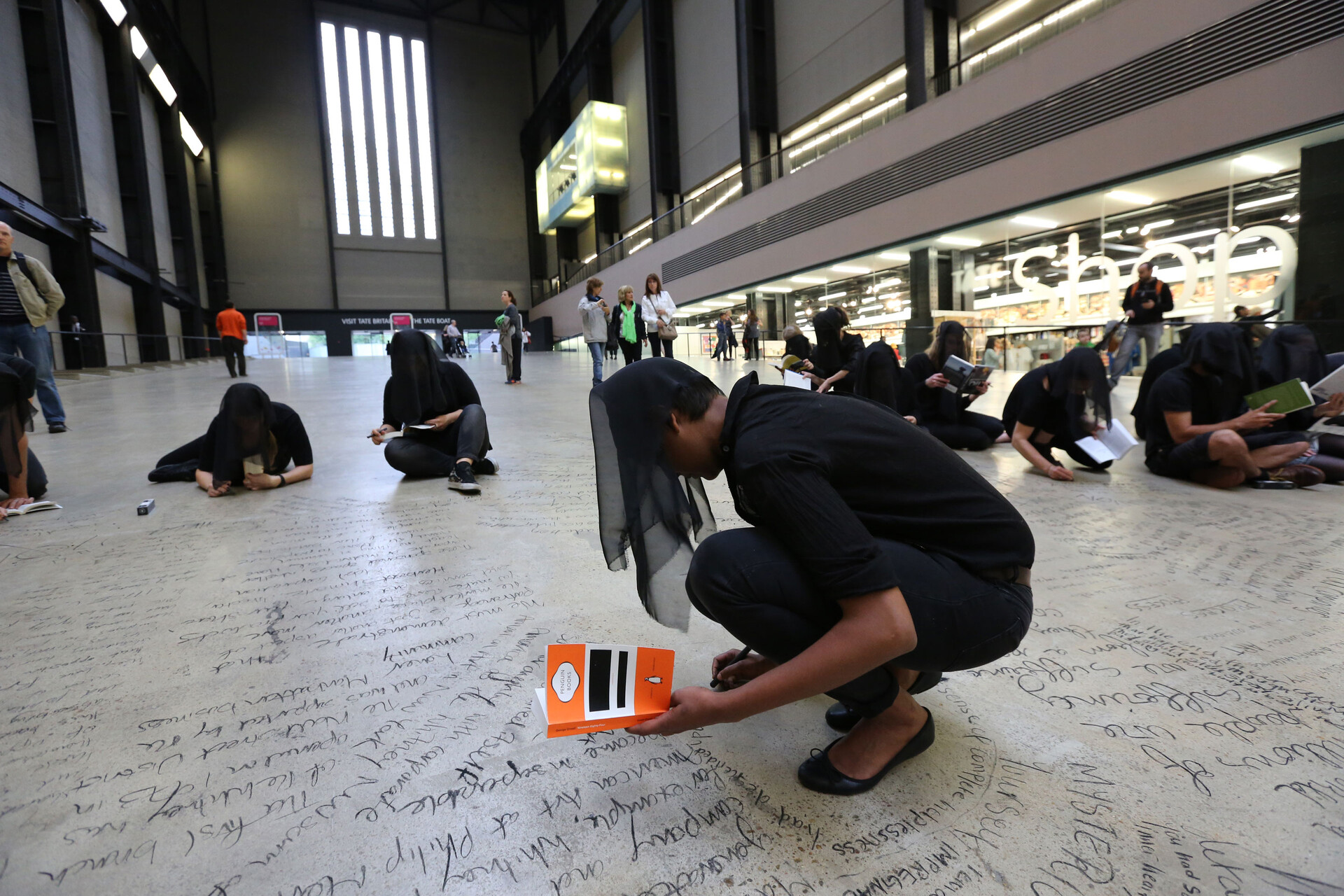

The concept of the language in common names the mode of communication through which traditions produce collectives, as collectives in turn produce traditions. When new traditions are introduced and old ones are resurrected, they become part of this productive process, both expanding and sharpening the means by which collective power is asserted. Collectives become known to themselves, build counterpower, and struggle over the meaning of their language through the repetition of common forms. It is also through repetition that collectives confirm the intention of their acts, symbols, slogans, and rituals. Take highway blockades as an example. One blockade is an anomaly—its meaning is indeterminate. Ten blockades suggest the emergence of an activist tactic. Ten blockades in ten different cities suggests that the tactic is spreading. Take the movement against the Coastal Gaslink pipeline in British Columbia, led by Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs. Earlier this year, a checkpoint at Unist’ot’en Camp, established on unceded Wet’suwet’en territory in the Pacific Northwest, inspired hundreds of blockades across Canada, shutting down the country’s logistical infrastructure for a month. One of the most effective blockades disrupted the rail lines between Toronto to Montreal. Situated on Tyendinaga Mohawk territory, a few hours southwest of the Mohawk Nation’s landmark 1990 blockade at Kanesatake (Oka, Quebec), the rail blockade awakened the power of a longer history of anti-colonial struggle. This example represents the potential for a tactic to echo both across space and time. Across the country, blocking a highway or rail line became a gesture of solidarity, a way of showing others that their messages were heard. Blocking traffic became a ritual—a choreographed action, in short—that anyone, anywhere, could perform in order to signal their fidelity to the struggle.

When we recognize a symbol, performance, or material act as an expression of our movement, it is not usually because an individual affiliated with the movement has claimed responsibility. More often, it is because we recognize it as an iteration, elaboration, or transformation of a tradition that we believe to be ours. When we insist that the tradition is ours, we enter the struggle over its interpretation, recognizing that if we want to express our collective power, we need to tell the story from our side. From this perspective, it does not actually matter who lit fire to Minneapolis’s Third Precinct during the recent George Floyd uprisings, or even whether “outside agitators” struck the match. What matters is that the action, which was undertaken by an organically composed group of people, became a catalyst that ignited the passions of millions. It stood as a symbol of revolutionary possibility—a call for collective response. Movements never start from scratch. Emerging from the material conditions of oppression and sparked by collective rage, movements build on the power that is latent in the culture, and through iterations of what came before.

One advantage of seeing movement-building from the perspective of the language in common is that it counteracts the politically halting tendency to deconstruct or dwell on left failure. Instead, it attunes our collective gaze to the traditions we are constructing, as well as to what our traditions inherit from the past. This was the lesson of Omaha elder Nathan Phillips’s iconic standoff at Lincoln Memorial, following the inaugural Indigenous Peoples March in 2019 in Washington, DC. Surrounded by dozens of high school students clad in Trump swag and shouting insults, the veteran organizer held ground. Standing inches from the group of students blocking his way, he chanted an American Indian Movement anthem from the 1970s as he courageously beat his drum. As Phillips explains, “When I got here to this point and started singing … that’s when the spirit took over.”[7] History was awakened in the repetition of song, underscoring the power of language to anchor the individual within the collective—a collective held up by comrades past and future. When we encounter a sign as an expression of the language in common, we recognize the force of history that is behind it, as well as the emancipatory future that it makes possible—even when faced with apparently insurmountable odds. As an affirmative language of difference that is built through collective work, the language in common allows the collective to see itself as a force within the movements of history.

Negating the Negation

In the midst of the resurgent BLM uprisings, many writers on the left praised the looting, property destruction, and monument removals that spread across the US and the globe, celebrating them as revolutionary acts of rupture. But almost as soon as the state began to regain social control, many of these same writers returned to their old hobbyhorse. They decided to announce the movement’s defanging at the hands of a coordinated counterinsurgency led by state and non-state actors.[8] With this trajectory in mind, we need to ask not only how our rebellions get subsumed, but also how the frameworks we use to interpret them unwittingly participate in this process of subsumption. How can we avoid amplifying our failures at the expense of what we achieve?[9]

The question is not only tactical, but also interpretive. When we evaluate our collective actions for their concrete material effects—for the damage they do at the human scale—we are immediately confronted with our powerlessness in the face of our enemy. This enemy not only holds the monopoly on legitimate violence (and is not afraid to use it), but also knows how to weather the storm. Capitalists build pushback into their budgets. They take out insurance policies to cover broken windows, arson, and lost profits. In advance of scandal, they contract public relations firms to protect their brands. Faced with the cunning and brute power of the capitalist state, how are we to see our uprisings as anything but futile tantrums—proof of our incapacity to move from rebellion to revolutionary change? The answer is in recognizing the ways that our concrete actions in the material world contribute to the language in common, through which we build and express our difference.

Social movements are not built by consensus or organized by central committees. They emerge when groups and individuals show a commitment to a common name (BLM, Occupy, NoDAPL, Gilets Jaunes, and so on), even when they disagree about its meaning.[10] Movements are not the positive constitution of an organizational form. They name the gap through which specific events, actions, gestures, slogans, and symbols combine to give shape to an emergent collective. Whether we decide to take a knee or burn a cop car, the action we choose gives meaning to every other action. Concrete actions give meaning to symbolic actions, making them sharp and infusing them with militancy. Symbolic actions give meaning to concrete actions, connecting them to a more expansive narrative of social transformation. The language in common mediates between the material and the symbolic, holding open the gap through which we struggle to determine our collective horizon.

When approached from the perspective of the language in common, our negations are negated, and transfigured into their positive form. It becomes possible to see our actions as additive, not merely subtractive. They are our songs, our dances, our rituals, and our performances. As the forms through which we distinguish our comrades from our enemies, they awaken the shared desire for collectivity that incites us and holds us together.[11]

Consider the removal of monuments that swept through public squares over the past several months. For years, activists have called for the removal of monuments to slave traders and genocidal colonists, arguing that such commemorations are a source of ongoing violence for the descendants of slaves and colonized peoples who are forced to encounter them on a daily basis. As “spatial acts of oppression,” monuments overdetermine the historical coordinates through which we encounter the world.[12] Monuments are propaganda for the ruling class. The durability of their material metonymically affirms the durability of the system of oppression that they commemorate, from which they were commissioned, and to which they owe their protection from the people who despise them. Monuments set the coordinates from which the world appears as a capitalist world.

Years of antiracist and anti-imperialist organizing to remove Confederate and imperial monuments, petitioned through open letters and public appeals to heritage officials, were largely stalled until people began taking matters into their own hands. This has been particularly evident in the wake of the George Floyd uprisings. On May 31, a monument to Confederate leader Charles Linn was toppled by BLM protesters in Birmingham, Alabama. It was followed by countless others across the US and around the world. As monuments began to fall, the tactic of monument removal and defacement became central to the language in common through which Black Lives Matter movements expressed their counterpower, and through which activists around the world identified themselves as comrades in the struggle. Every time people came together to vandalize, behead, or topple a monument to oppression, they answered a call that preceded them.When people remove monuments to white supremacy, their actions are not simply subtractive. These actions live on as image and myth, contributing to the array of gestures and symbols that build and express difference. Recall the summer of 2015, when activist Bree Newsome famously climbed the flagpole at the South Carolina state capitol to pull down the Confederate flag. The flag was raised back up within forty-five minutes, but the damage was done. Images of Newsome’s action circulated widely, raising pressure on South Carolina authorities to permanently remove the flag. The point we want to emphasize is not that Newsome’s action led to concrete change at the state capitol (which it did), but that the iconic image of her action became a flag for antiracism in the US, fueling many of the fires that have since been burning. Her action became generic through its media circulation, converting flagpoles around the country into active sites of struggle—places where antiracists can assemble to assert their collective power. Such tactics of resistance activate the capitalist world as a site of struggle, demonstrating how oppressive monuments can be split, seized, and reclaimed as our own.

Remapping the World

In The Colonial Lives of Property, Brenna Bhandar examines the imperial history of cartography. Bhandar’s 2018 book reminds us that the project of mapping the capitalist world was not only one of development and modernization, but also one of erasure. The colonial concept of terra nulliuswas the ideological companion to violent dispossession, and an antecedent to capitalist realism. It enabled settler capitalists to rationalize the imposition of private property relations on Indigenous land, burying both the precolonial history of the land and the common relations that sustained it. The world in common, which was carved up and partitioned in the making of the capitalist world, was not entirely eradicated in the violent processes of genocide, dispossession, and forced assimilation. Repressed in the capitalist map are, in Bhandar’s words, “ways of relating to land that are not premised on the exploitation of its resources and the often-unbridled destruction of the environment for corporate profit.”[13] The problem is not that the whole world has been subsumed by capitalism, but that we have been trained to see it from a capitalist perspective. This training has blinded us to the gap of collectivity that capitalism cannot enclose. It is not just that another world is possible. It is already here, embodied in the desires, practices, modes of belonging, ways of relating, and forms of organization that sustain collective life. To see this other world, we need a place to stand within it.

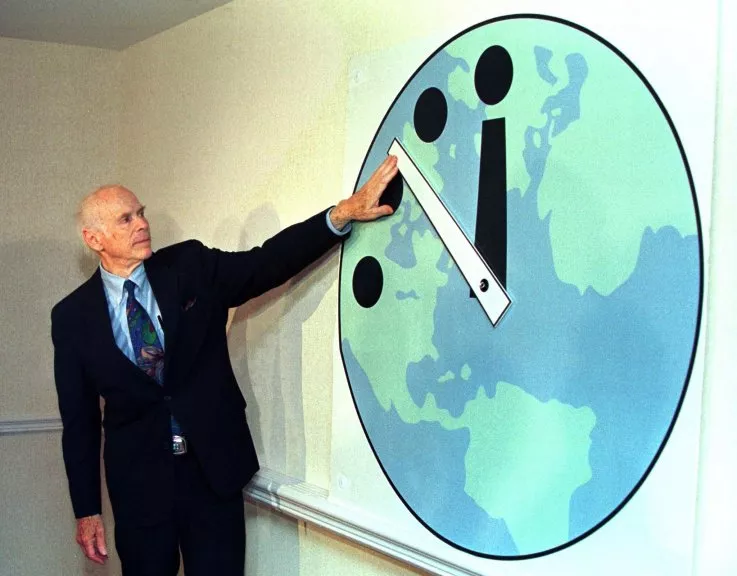

The language in common is the form through which our collective difference is asserted and organized around. When we can see our difference, we can see the capitalist world not as a totality, but as a world cut in two. Capitalists recognize the power of our language to communicate a relation to the world that is not based on extraction and profit. They interpret both our languages and our relations as a threat. Our languages of difference become expressions of counterpower when we affirm that they do, in fact, represent a threat to the capitalist world. The concept of the language in common allows us to see how social movements communicate across space and time, and how our shared images, rituals, and signs both produce and make visible our collectivity. The language in common is not, however, a substitute for political organization. Jodi Dean reminds us that it is not only a question of “constructing the political collectivity with the will and capacity to bring an egalitarian world into being,” but also of establishing the infrastructures and forms of organization necessary to “hold open the space for the emergence of such a will.”[14] How do we move from catching fleeting glimpses of this egalitarian world to actually instituting it at scale?

Capitalist realism has trained us to believe that there is no outside—that every site, object, and institution marks another spot on the capitalist map. This is as true of the public school system as it is of the American Museum of Natural History. Holding out hope that “revolution is in the streets,” we retreat from social institutions and infrastructures, surrendering them to the capitalists who, left uncontested, use them as weapons against us. We justify this result by insisting that these institutions and infrastructures were founded to serve the ruling class; there never was an alternative. Our only option is to burn them to the ground and declare terra nullius for a second time.

When we define sites, objects, or institutions as inherently capitalist, we slip into the same pattern of thought that we do when we write off our traditions as soon as Nancy Pelosi performs them. We deny our collective agency and become conspiracists for the capitalist class. We affirm the power of the regime of extraction and exploitation, observe its omnipresence in our everyday lives, and declare it eternal. Our gains or advances appear as complicity and compromise. We adopt the “deflationary perspective of the depressive” that Fisher described, accepting rather than acting against the realism that capitalism sells.[15]

Instead of spending our time proving the existence of fascism or the flourishing of capitalism, we would be better off promoting conspiracies about our own power. This does not mean exaggerating how many people show up to our rallies, but it does mean training ourselves to see the signs of our collective power in every site, symbol, and institution. The language in common is not a thing. It cannot be measured or verified as real or fake, true or false. Nor is it constructed through the democratic decision-making process, where we are meant to accept the lowest common denominator, to which the least number of people disagree. Rather, the language in common nominates language as a site of struggle. We struggle for our language by believing in it, committing to it, working with it, iterating on it, and insisting on the collective power expressed in it. When we become conspiracists of our own power, we see the power of our language. We see our negations as affirmations, our acts of disobedience as obedient to another law.

Chief Rueben George of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, a leader in the struggle against the Trans Mountain Pipeline, speaks of the Indigenous law that governs his community’s resistance to fossil fuels and the settler-colonial state as follows: “We don’t obey laws if they are unjust laws.”[16] Tsleil-Waututh law comes with certain obligations. As Indigenous lawyer and Tsleil-Waututh chief Leah George-Wilson explains, “Our fight against the pipeline is based on our Aboriginal Rights and Title as supported by our Indigenous Law. It is according to our law that we protect the environment and our territory … We have the duty, the obligation to ensure the safety of the land, water, SRKW [Southern Resident killer whales], and all wildlife.”[17] Tsleil-Waututh law bears no relationship to settler law. It is affirmative: it defines what is right and just. It is grounded in a non-dominating, non-exploitative relation to the land, and a commitment to steward the land for future generations. From this perspective, when the future of the land is in question, acts of resistance—from checkpoints to occupations and blockades—are actually obedient. They adhere to another law, based on a different form of justice, which subordinates profit to the future of human and nonhuman life. This other law represents the baseline for noncapitalist modes of belonging and forms of social organization. Language schools, social centers, museums, and other institutions are built in respect to this law. This concept of law asks us to move from a politics of becoming ungovernable to one of governing ourselves differently—of relating to the world as a world in common, building language and culture around this relation, and constructing an infrastructure to support it.

As we expand our conspiratorial vision into territories governed by settler capitalist law, we see what is common within every enclosure, and we set to work at liberating it. We do not just protest pipelines. We build, protect, and expand a world in which pipelines do not belong. The Lummi Nation’s Totem Pole Journey puts this world-building agenda into practice. Each year since 2013, the House of Tears Carvers of the Lummi Nation carve a totem pole, put it on a flatbed trailer, and bring it to sites of environmental struggle across the US. For the past three years, Not An Alternative has been supporting the journey. The House of Tears Carvers visit Indigenous communities that are not yet allies, as well as farmers and ranchers, scientists, and faith-based communities, engaging each group in a ceremony led by Lummi elders. Each time, participants are asked to touch the totem pole—to give it their power, and to receive its power in turn. The goal of the Totem Pole Journey is to connect communities on the frontlines of environmental struggle, and to build, through ceremony, a broad and unlikely alliance of people against pipelines—an insistent “we” that did not previously exist. Lummi councilman Freddie Lane likens the totem poles to batteries: they are charged with the energy of those who touch them, and as they travel, they give the people energy in turn.

The Totem Pole Journey offers an approach to the question of monuments from which the non-Indigenous left can learn. The Lummi Nation’s totem poles are not anti-monuments, nor are they counter-monuments, which would work in equal but inverse relation to the monuments that are designed for oppression. The poles do not impose power from above, but rather concentrate collective power from those who surround them. In this way, these poles anchor comradely relations between people to a non-dominating relation with the land. Mobilizing traditional cultural objects as part of a solidarity-building infrastructure, the Lummi carvers model a transition from the language in common to an infrastructure for the common. The totem poles draw a line of division—a line in the sand against the fossil-fuel industry, but also a line of connection between the communities they engage. As they draw this line, they become living monuments to life beyond extraction.

When we move from the language in common to the infrastructure for the common, we do not give up the symbols, rituals, and monuments to our power, nor do we give up the struggle to determine their meaning. Rather, we commit to our traditions, connect them to others, and build institutions around them. We find our coordinates and coordinate our struggles. As we aggregate our collective power against the engines of extraction and exploitation, we set the foundation from which we can remap the world as a world in common.

Not An Alternative (est. 2004) is a collective that works at the intersection of art, activism, and theory. The collective’s latest, ongoing project is The Natural History Museum (2014–), a traveling museum that highlights the socio-political forces that shape nature. The Natural History Museum collaborates with Indigenous communities, environmental justice organizations, scientists, and museum workers to create new narratives about our shared history and future, with the goal of educating the public, influencing public opinion, and inspiring collective action.

“The Language in Common” was originally published in e-flux journal #113 (November 2020).

- [1] For example, see Pat Rough, “In Budget Vote, City Council Fails to Heed the Demands of Black Lives Matter,” The Indypendant, July 1, 2020 →.↩

- [2]Jodi Dean, The Communist Horizon (Verso, 2012), 12.↩

- [3]Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Zer0 Books, 2009).↩

- [4]Glen Sean Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 9.↩

- [5]Nick Estes, Our History is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (Verso, 2019), 21.↩

- [6]Karl Mathiesen, “How to Change the World: Greenpeace and the Power of the Mindbomb,” The Guardian, June 11, 2015 →.↩

- [7]Julian Brave NoiseCat, “His Side of the Story: Nathan Phillips Wants to Talk about Covington,” The Guardian, February 4, 2019 →.↩

- [8]Martin Schoots-McAlpine, “Anatomy of a Counter-Insurgency,” Monthly Review, July 3, 2020 →.↩

- [9]For an anarchist’s account of the left’s compulsion to see its victories as failures, see David Graeber’s posthumously published “The Shock of Victory,” Crimethinc, September 3, 2020 →.↩

- [10]Not An Alternative, “Counter Power as Common Power,” Journal of Aesthetics and Protest, no. 9 (2013) →.↩

- [11]Jodi Dean theorizes collective desire in The Communist Horizon and also in Crowds and Party(Verso, 2016).↩

- [12]Robert Bevan, “Truth and Lies and Monuments,” Verso Blog, June 23, 2020 →.↩

- [13]Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (Duke University Press, 2018), 193.↩

- [14]Dean, Crowds and Party, 251.↩

- [15]Fisher, Capitalist Realism, 5.↩

- [16]The concept of an “unjust law” invokes Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” (April 16, 1963), which argues that “one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.” See →.↩

- [17]Chief Leah George-Wilson, “Tsleil-Waututh Nation’s Fight Continues,” MT+Co, September 17, 2019 →.↩