The world is in flames. From California and Oregon to Australia and the Amazon rainforest, the largest fires on record are spreading across the planet, bathing their surrounds in an unsettling red light for days at a time. Floods, droughts, hurricanes, deadly heat waves, and other climate-fueled disasters are tearing across the landscape. The Gulf Stream is on the brink of collapse. The predictive models of modern science no longer point to stable patterns, but to the volatile force of the unknown.

The combined history of colonialism and capitalism has been marked by the unceasing effort to control the human and nonhuman forces that threaten to bring about its end. Climate change is only the latest threat, but it is unrivaled in its power to transform the world. The incapacity of science, states, and corporations to manage the threat of climate change is forcing a crisis in the colonial regime of knowledge that underpins capitalism—the groundwork of the tradition of natural history that emerged from the social institution of modern science and the political project of imperialism over the last three centuries.

This text introduces a perspective that interprets natural history neither simply as the study of “nature,” ecosystems, or premodern cultural traditions, nor as an intrinsically colonial enterprise, but as a history of struggle between two incommensurate relations to the world: one governed by a logic of extraction and enclosure and another that relates to the world as a world in common that cannot be enclosed. This struggle is not waged on the terrain of the natural, but over its interpretation, not over what is “intrinsically in nature” (Gould, 1988), but over the relation to the world that ought to be naturalized.

Naturalizing the Capitalist World

From Europe, to China, to the Indo-Islamic world, long traditions of natural history have emerged, and sometimes converged, over the course of human history. But by most accounts (Raj, 2007; Basalla, 1967), natural history is understood as the sole dominion of the West—as a project that emanated outward from the colonial metropoles to survey the entire world with the empiricist tools of modern science. The first large-scale natural history museums and botanical gardens were established in Europe and Great Britain to put this project on display. There, biological and geological specimens, premodern cultural artifacts, human and nonhuman remains, and other “curiosities” bought and stolen by explorers and colonists were submitted as material evidence for scientific investigation.

In its institutionalized form, the imperial project of natural history constructed a picture of the world through the spoils of imperialist expansion. Its collections demonstrated the military power of the metropole, and its methodologies for interpreting these collections asserted the supremacy of Western empiricism and modern science. This tradition of natural history rested on the assumption that experts could understand the world by extracting and studying its constitutive parts. It claimed its object as an individuated, knowable thing, part of the wealth of natural resources available for possession, profit, and scientific probing.

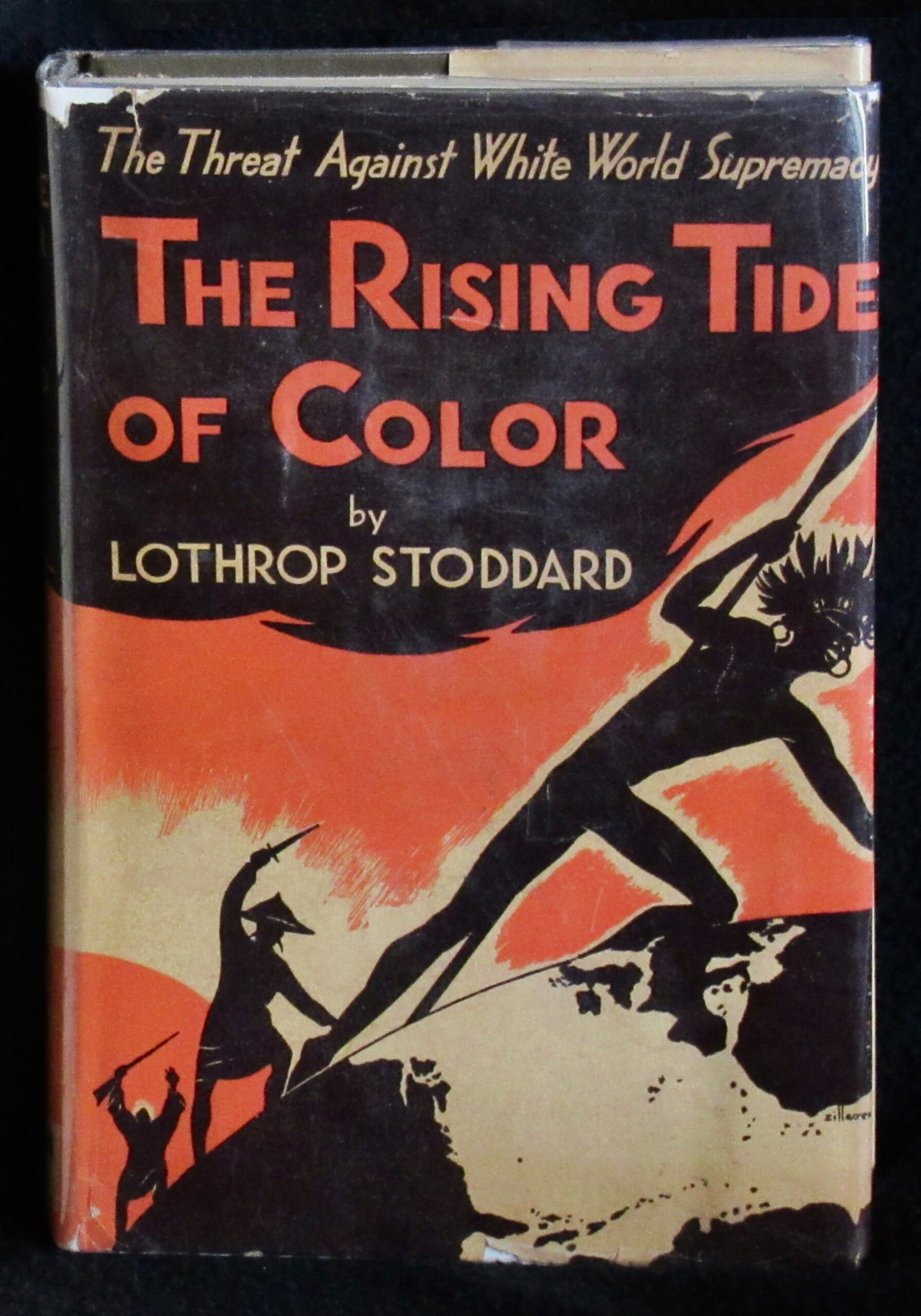

This basic premise came to prominence through Charles Darwin’s theses on evolutionary biology, which grafted a Malthusian logic of individual competition onto the world as a whole. According to this logic, organisms and their environments are not seen to be mutually dependent; rather, as Richard Lewontin (1991) explains, in the Darwinist evolutionary struggle “organisms find the world as it is, and they must either adapt or die.” Generations of conservative economists appropriated Darwin’s theory of natural selection to explain the dynamics of competitive advantage under capitalism, rationalizing capitalist domination as an evolutionary fact. The “survival of the fittest” thesis, proposed not by Darwin but by the social Darwinist philosopher Herbert Spencer, galvanized the eugenics movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which, unsurprisingly, found vigorous support from the world’s most influential natural history museums. The dominant ideology of natural history, which embedded both the logic of competition and the violence of extraction into the project of scientific inquiry, served to reinforce social Darwinism’s capitalist and white-supremacist conclusions.

All in the name of science, lands were torn up, bodies were exhumed, and skulls were examined, compared, and classified according to racist typologies. The living subjects of ethnographic study, too, were cast as primitive and prehistoric, banished from the historical time of the ethnographer (Fabian, 1983). “Objects for observation,” Vine Deloria, Jr. (1969: 81) argued, were always implicitly “considered objects for experimentation, for manipulation, and for eventual extinction.” Prioritizing the physical materialism of the world and its ecosystems, natural historians submitted everything sacred to the profane logic of equivalence—the law of capitalist exchange. In this and other ways, natural history was part of a broader plot to remap the world as a capitalist world, to turn what John Locke (1689) called the “wild Common of Nature” into a source of profit.

The microscope is only one of many tools deployed in the ongoing project of naturalizing the capitalist world. By means of violent dispossession, deceitful and broken treaties, and the declaration of terra nullius, territories collectively held for generations by peasants, Indigenous peoples, and maroon communities were, and continue to be, stolen, enclosed, and submitted to the abstract logics of private property. Through the legal abstraction of land titling, territories were commoditized and made fungible—leveraged as credit, exchanged, and subjected to financial speculation in a world market (Bhandar, 2018: 97). It is not that the transition to capitalism catapulted idyllic premodern cultures into history, undoing some illusory primordial innocence as traditional anthropology and historiography would have it, but that in recoding land as property, collective systems of land tenure based on kinship, intergenerational stewardship, spiritual value, or communal labor have been rendered both illegitimate and illegible—from the capitalist point of view. Displaced and dispossessed, people around the world have been put to work, forced to toil not for the land and each other, but for capital.

Haunting Natural History

This ongoing process of enclosure and expropriation, which Marxists call “primitive accumulation,” has not only been a means of asserting sovereign rule over Indigenous land and establishing capitalist economic relations in new territories, but also a means of repressing preexisting modes of life, knowledge systems, and land-based practices that cannot be reconciled with the demands of colonialism or capitalism. Agrarian commons, subsistence farms, systems of mutual aid, and Indigenous practices of land and water stewardship share one thing in common: an insistence that the world is not a resource to be extracted, but, as Glen Sean Coulthard (2013: 60) puts it, part of a system of reciprocal relations and obligations between humans and nonhumans that demands mutual respect, non-domination, and nonexploitation. Writing about the land-based practices that structure the theory and practice of Indigenous anticolonialism in North America, Coulthard (2013: 13) names this perspective “grounded normativity,” underscoring how Indigenous struggles for land are also deeply informed by the land. The ethics of reciprocity, which is differently expressed in Indigenous and non-Indigenous traditions of resistance, is not a straightforward inversion of the colonial logic of extraction and enclosure. It does not simply subordinate human life to the lives of animals, plants, water, and land. Rather, it underscores how their interests are bound together in the production and reproduction of life.

During and after the transition to capitalism, collectivist societies across the world, even within Europe itself, have struggled within and against their conditions of survival to build alternative knowledge systems from their own embodied experiences, clarifying and sharpening place-based traditions and ways of knowing in and through their collective struggles for liberation. In the paranoid minds of the capitalists, these constructed traditions, knowledge systems, and world-building practices are not only incompatible with the colonial logic of extraction; they also represent its combative antithesis, expressing what nineteenth-century crowd psychologist Gustav Le Bon (1897: xvi) characterizes as an emotional, unreasoning, and barbaric “primitive communism” that needs to be destroyed.

There have not always been direct material connections between “communistic” peasants, heretics, maroons, women, workers, colonial subjects, and Indigenous peoples, whose appearances have spanned continents and historical periods. These groups have also related to the land they have traversed in distinct and sometimes contradictory ways. Nevertheless, oppressed communities across the world have been perceived by the capitalists as instantiations of one collective body, whose inborn fidelity to the common will, left to itself, bring about capitalism’s end (Linebaugh and Rediker, 2000). Faced with the endurance of this capitalist conspiracy, it is no surprise that colonial and capitalist forces continue to brutally attack collectivist societies and the cultures that ground them, specifically targeting the reciprocal relation between peoples, the animals they rely on for their survival, the lands they steward, and the traditions that connect them to their ancestors.

So that it could stand as an objective and ideologically neutral authority on the nonhuman world, the imperialist tradition of natural history has served the function of eradicating knowledge systems that it has understood to be in competition. Natural historians have long participated in this project by treating societies they could not understand as barbaric, premodern, and extinct, even as these same societies held their ground and maintained their languages, cultural traditions, and ways of knowing. The modern concept of natural history was thus not only formed on a bedrock of colonialism; it has also required the constitutive exclusion of its other: a natural history built on reciprocity, not extraction. This other natural history was not annihilated, only obscured—symbolically imprisoned in museum vaults and display cases, where it remains as a specter that haunts natural history from within.

Red Natural History

This other natural history, in distinct opposition to and in struggle with colonial, capitalist historicization and expropriation, is not simply alternative, peripheral, or marginal to the disciplines, methodologies, institutions, and practices that are usually associated with natural history. Rather, like a repressed trauma, it constitutes the disavowal at the center of natural history and its related disciplines. It is reflected in the life-affirming processes that have been deemed out of control because they refuse to stay within the bounds of privately held allotments: the weeds that settlers try to keep from returning to their manicured lawns; the cyclically returning forest fires that threaten the value of the mansions that get in their way; the surging waters that dams try to hold back; the climate refugees shaking down border walls. Not An Alternative is working with a group of Indigenous and non-Indigenous theorists, historians, ethnobotanists, geographers, landscape architects, artists, and activists to give a name to this other natural history, which we propose to call Red Natural History.

Red Natural History names a commonality shared between the peoples, worldviews, traditions, and practices that have been the objectified subjects of natural history, taking as axiomatic that the world is not a wealth of natural resources but a world in common. The world in common is not identical to “the commons.” The commons is a territorialized site that can be enclosed, whereas the world in common exceeds every attempt to consume it, make it knowable, or enclose it in the property form. It defines a comradely and reciprocal relation between humans and nonhumans, a relation of mutual obligation that is not naturally occurring, but that is made to exist through the sustained, collective effort to produce it.

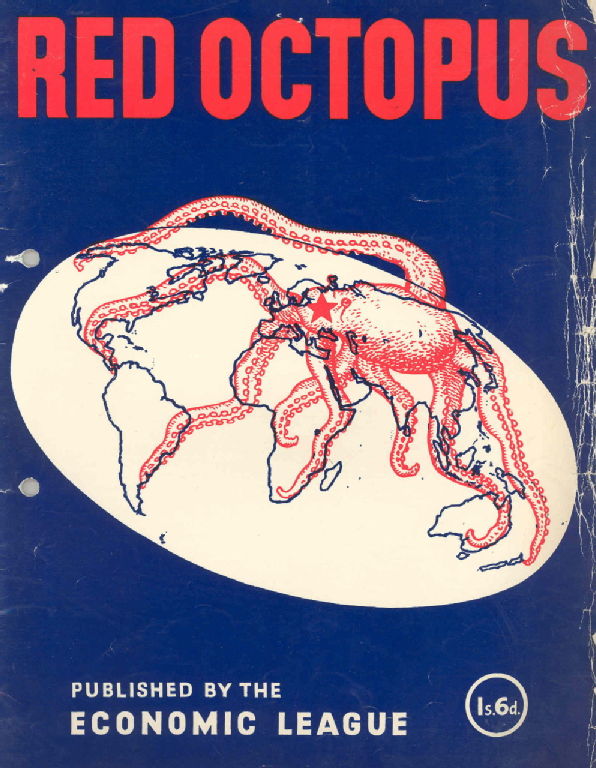

For Not An Alternative, the “Red” in Red Natural History designates the divide in natural history, signaling an alignment with those forces that have always been illegible to the colonial regime of knowledge, which represent the dangerous idea that something might exist beyond capitalist management and control. It signals our fidelity with the long history of struggle to make the world a world in common—with the intergenerational movements against enclosure, colonization, exploitation, and extraction that have assembled under the red flag, the red star, the red fist, the red square, and the red line.

For centuries, the purveyors of colonialism and capitalism have targeted groups that relate to the world as a world in common, waging brutal campaigns of extermination, enclosure, and forced assimilation. These campaigns have been devastating but left incomplete. The world in common, as a relation to the land and the horizon for our politics, comes into view when we hold in our minds the memory of the ancestors who came before us. It is awakened when we recognize how our traditions of resistance (Estes, 2019) open ways of understanding the world that enable us to see differently, when we build on the life-affirming knowledge of past generations, and when we pick up the struggle to protect the world for our descendants.

As a conscious project of “selecting and re-selecting our ancestors” (Gilmore, 2017), Red Natural History asks us to ground contemporary struggles for the land and all its inhabitants in the struggles of those who came before us, to draw a line from the past into a future that capitalism has barred from view. It asks us to build on the revolutionary work of the True Levellers (better known as the Diggers), who in the midst of the English Civil War of 1642–51, dug up the hedges at St. George’s Hill to plant crops for the poor—an act of negation meant to affirm and reveal the world in common beneath the enclosures imposed upon it (Winstanley, 1649). It asks us to learn from the maroons of Dominica, who, having fled from the plantations to the mountains throughout the eighteenth century, held their ground for decades not simply by fortifying their camps, but also by learning from and living with a wild terrain that the French and British armed forces were unable to tame (Malm, 2018: 13-15). It asks us to remember the Guinnean revolutionary Amilcar Cabral (1972), who, leading the guerrilla movement against the Portuguese occupation from 1963 to 1973, declared that on the flat terrain of Guinnea-Bissau, “Our people are our mountains.” It asks us to stand behind the struggles of Indigenous peoples around the world—to bear witness not only to the blockades they build, but also, as Leanne Betasamosake Simpson writes, to “the rich sites of Indigenous life” existing behind them, where “you will witness a radically different political existence and ethical orientation, in spite of the dominance of colonialism.” Red Natural History’s task is not simply to show how people have “made kin” with nonhuman others (Haraway, 2016), but to build from the long and ongoing history of reciprocity in struggle. The point is not to chronicle a linear history, to get the facts right, but to see past and present struggles as part of one movement to decisively shift the direction of natural history, from progressive degradation to abundance and collective flourishing.

Our collective’s understanding of Red Natural History is inspired by a long history of anticolonial struggle, but, to be clear, it is not based on a neo-primitivist imaginary. It does not look to the past to discover an authentic, precolonial ideal, but to build on the power of those who, throughout history, have struggled to maintain reciprocal relations in the world. It sees tradition as something that is invented, worked on, put to use, and transformed in the intergenerational movement to secure just relations with the land and each other. While the future is not behind us, the accumulated history of struggle empowers and guides us in our collective work.

The work of Red Natural History is to force the dialectics of natural history into the open. To see dialectically is to see the split in the totality, the dynamic contradictions through which historical change is made. The operative division in natural history is not between the human and nonhuman, as the New Materialists argue, nor is it between nature and society, as in the writing of Jason W. Moore (2015). Rather, it is between two fundamentally irreconcilable perspectives on the world: one that sees the world as a wealth of natural resources and the other that sees the presence of the world in common within and beyond every enclosure. These perspectives enforce distinct relations between humans and nonhumans—reciprocal or extractive—and, as a consequence, different obligations—to the reproduction of life, or the reproduction of capital. To see natural history through this schema is to register the divisions through which the world itself transforms, not in the interest of healing the divide, but of taking a side: oppressor or oppressed, extraction or reciprocity, individual or collective, enclosure or common. When we take the side of the common, we open a path for new alliances, not through the intersection of identities, but through a shared relation to the world. As a mode of seeing historical change, Red Natural History mobilizes its adherents as a divisive force—within, against, and towards an emancipatory future.

How, then, do we relate to the signs telling us that the world we live in is coming to an end? Do we stand by in horror, interpreting the storms touching down with increasing fury as evidence that there is no alternative to mass extinction? Do we rest assured that big tech will save the capitalist world from ruin? Or do we interpret the arrival of the storm as a sign that the red specter has awakened to support the oppressed people of the world in their efforts to plot the only path forward?

The ongoing and accelerating effects of climate change have launched the planet into a perpetual state of emergency, but the meaning of this emergency is not locked in. As a perspective and a praxis, Red Natural History urges those of us who take the side of the common to see ourselves as part of the storm that arrives from the past, not to produce chaos, but to rupture the status quo, draw capitalism’s structural violence and injustices into the open, and orient our struggles for a livable and egalitarian future for all.

References

Basalla G (1967) The Spread of Western Science. Science 156 (3775): 611–22.

Bhandar B (2018). Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership.Durham: Duke University Press.

Cabral A (1972). Our People are Our Mountains: Amilcar Cabral on the Guinean Revolution. London: Committee for Freedom in Mozambique, Angola & Guine.

Coulthard GS (2013) Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Deloria V Jr (1969) Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. New York: MacMillan.

Estes N (2019). Our History is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance. Brooklyn: Verso.

Fabian J (1983) Time and The Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gilmore RW (2017). Abolition Geography and the Problem of Innocence. In Johnson GT and Lubin A (eds) Futures of Black Radicalism. Brooklyn: Verso.

Gould SJ (1988) Kropotkin Was No Crackpot. Natural History 97(7): 12–21.

Haraway D (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, Duke University Press.

Kapil R (2007) Relocating Modern Science: Circulation and the Construction of Knowledge in South Asia and Europe, 1650–1900. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Le Bon G (1897) The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. 2nd Edition. New York: MacMillan.

Lewontin RC (1991) Biology as Ideology: The Doctrine of DNA. Concord: Canada Broadcasting Corporation and House of Anasi Press.

Linebaugh P and Redkier M (2000). The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic. Boston: Beacon Press.

Locke J (1689) Second Treatise of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Malm A (2018). In Wildness Is the Liberation of the World: On Maroon Ecology and Partisan Nature. Historical Materialism 26(3): 3-37.

Moore JW (2015). Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. Brooklyn: Verso.

Simpson, LB (2021). A Short History of the Blockade: Giant Beavers, Diplomacy, and Regeneration in Nishnaabewin. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press.

Winstanley G (1649). The True Levellers Standard Advance: Or, The State of Community Opened, and Presented to the Sons of Men.

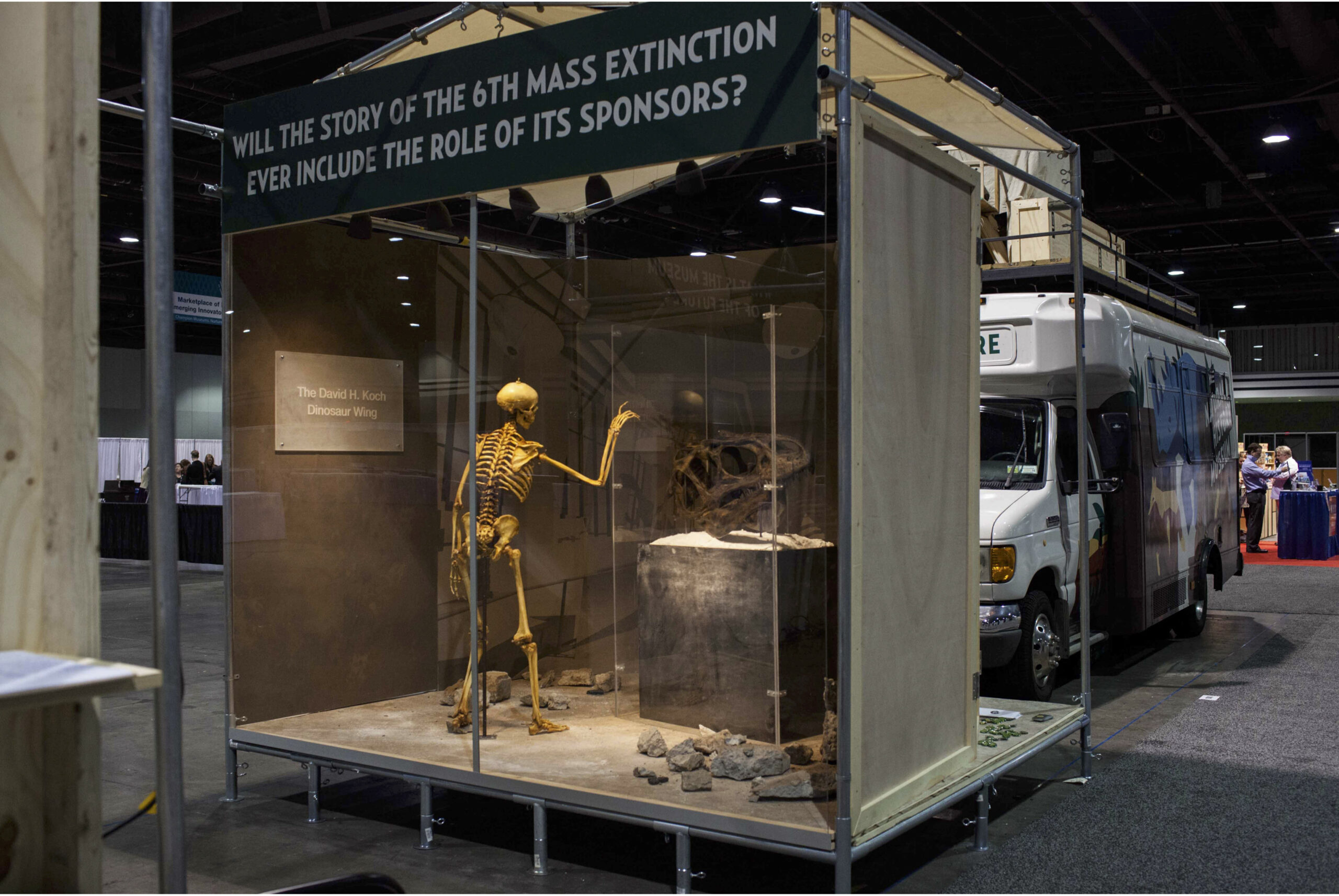

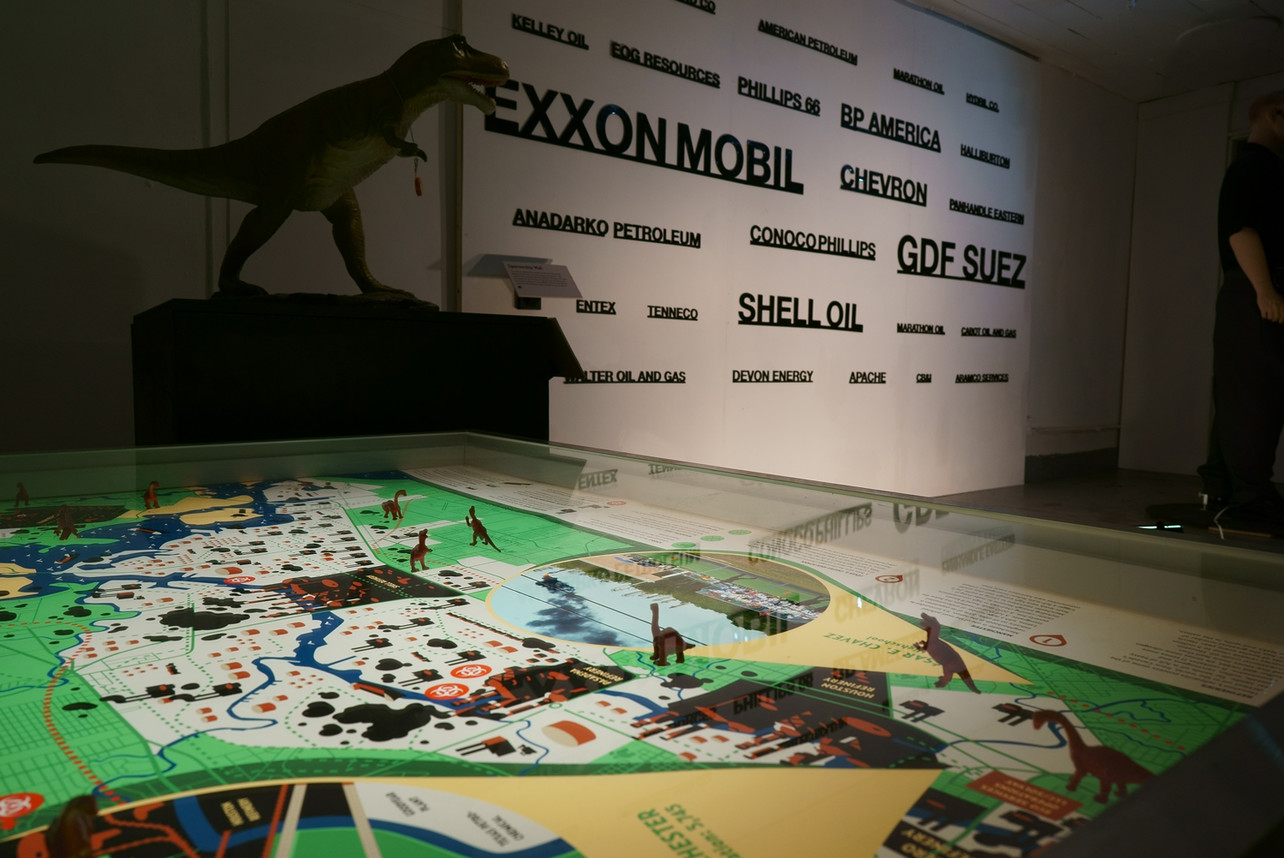

Not An Alternative (est. 2004) is a collective that works at the intersection of art, activism, and theory. The collective’s latest, ongoing project is The Natural History Museum (2014–), a traveling museum that highlights the socio-political forces that shape nature. The Natural History Museum collaborates with Indigenous communities, environmental justice organizations, scientists, and museum workers to create new narratives about our shared history and future, with the goal of educating the public, influencing public opinion, and inspiring collective action.