“We humbly ask permission from all our relatives: our elders, our families, our children, the winged and the insects, the four-legged, the swimmers and all the plant and animal nations, to speak. Our Mother has cried out to us. She is in pain. We are called to answer her cries. Msit No’Kmaq—all my relations!”

—Indigenous prayer

“On the brink of crisis and major global collapse, museums are, and need to be, agents for change.”

—Valine Crist, Haida Nation, at the ICOM NATHIST conference Anthropocene: Natural History Museums in the Age of Humanity

In the summer of 2016, in the middle of brown flatlands on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation near Cannon Ball, North Dakota, a sprawling camp of tepees, tents, and RVs appeared. Members of more than 300 Native Nations and several thousand supporters formed an unprecedented alliance against the proposed Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), which, despite tribal opposition, was set to cut through Sioux territory and across the Missouri River. DAPL risked jeopardizing the primary water source not only for the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, but also for 17 million people downstream.

Standing Rock captured headlines around the world and held the attention of millions. It invoked the horrifying memory of Wounded Knee, where more than a century ago hundreds of Lakota people were massacred by the US Cavalry for protecting their treaty lands from the encroachment of gold prospectors. This time, it felt like maybe if we did something, the outcome could be different.

In an open letter, more than 1,400 museum directors, archaeologists, anthropologists, and historians joined the Standing Rock Sioux in denouncing the company behind DAPL for desecrating ancient burial sites, places of prayer, and other significant cultural artifacts sacred to the Lakota and Dakota people. This letter was initiated by my institution, The Natural History Museum in Brooklyn, New York.

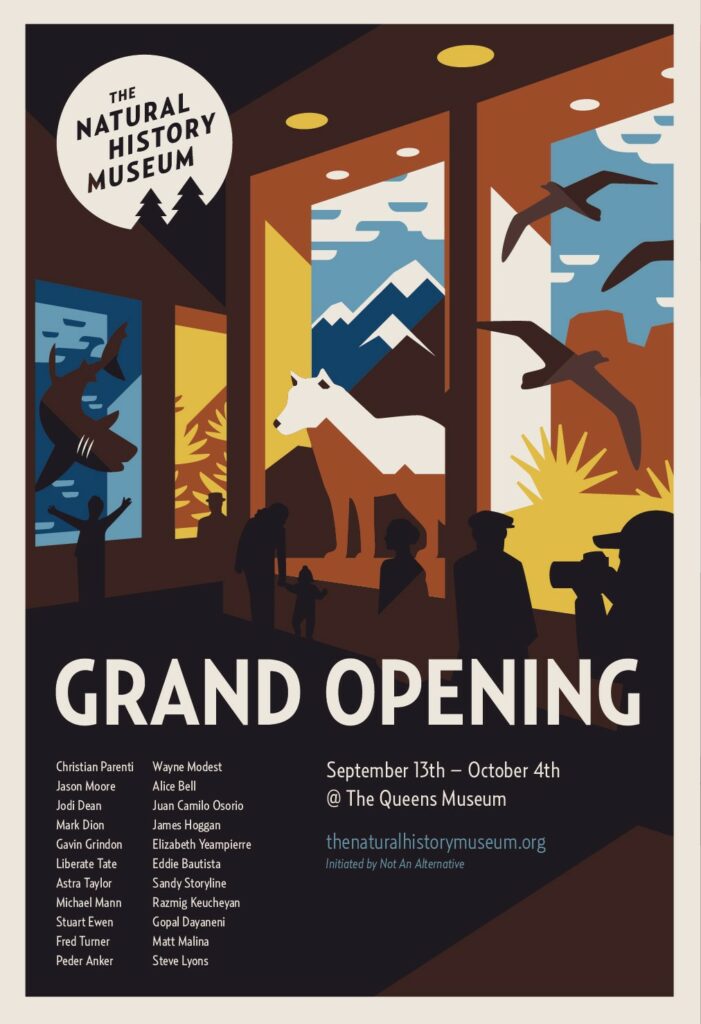

The Natural History Museum was founded in 2014 as both an institutional transformation project and a traveling museum. With decades of experience in both community organizing and exhibition development, we serve as a “skunkworks” for the museum sector—an independent research lab that develops projects that enable museums to try new forms of collaboration and public engagement programming, use their influence, and increase their relevance.

We believe that to be relevant in this time of environmental crisis, museums must move beyond the ambition to just be sustainable and carbon-neutral. We must also address and support the needs of frontline and fence-line communities that are struggling for a more just and sustainable world for all.

Being environmental stewards within this context means we need to align our practices with the global climate and environmental justice movement. This movement is led by Indigenous communities and born from cultures and bodies of knowledge that are already present—as artifacts, stories, and didactics—in the Native halls of the country’s natural history museums. In the post-Standing Rock era, these objects are charged with new meaning and significance. Through their curation and interpretation, we can connect history to the present—and impart lessons for the future.

‘Kwel’ Hoy: We Draw the Line’

Many American Indian and Alaska Native tribes face an array of health and welfare risks stemming from environmental problems, such as surface and groundwater contamination, illegal dumping, hazardous waste disposal, air pollution, mining waste, and habitat destruction. They are the first to experience the effects of climate change, yet they contribute the least to environmental degradation. Indeed, while Indigenous communities inhabit just 2 percent of the world’s land mass, they steward 80 percent of its biodiversity.

Leaders in the US museum sector have already begun questioning how they can begin to address Indigenous responses to climate change. The theme for the 2017 ICOM NATHIST (the International Council of Museums Committee for Museums and Collections of Natural History) conference was the Anthropocene Era—in which humans are not simply one species in a planetary ecosystem but a force that is modifying all of nature. The conference, at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) in Pittsburgh, explored how natural history museums can interpret the implications of the Anthropocene for the public.

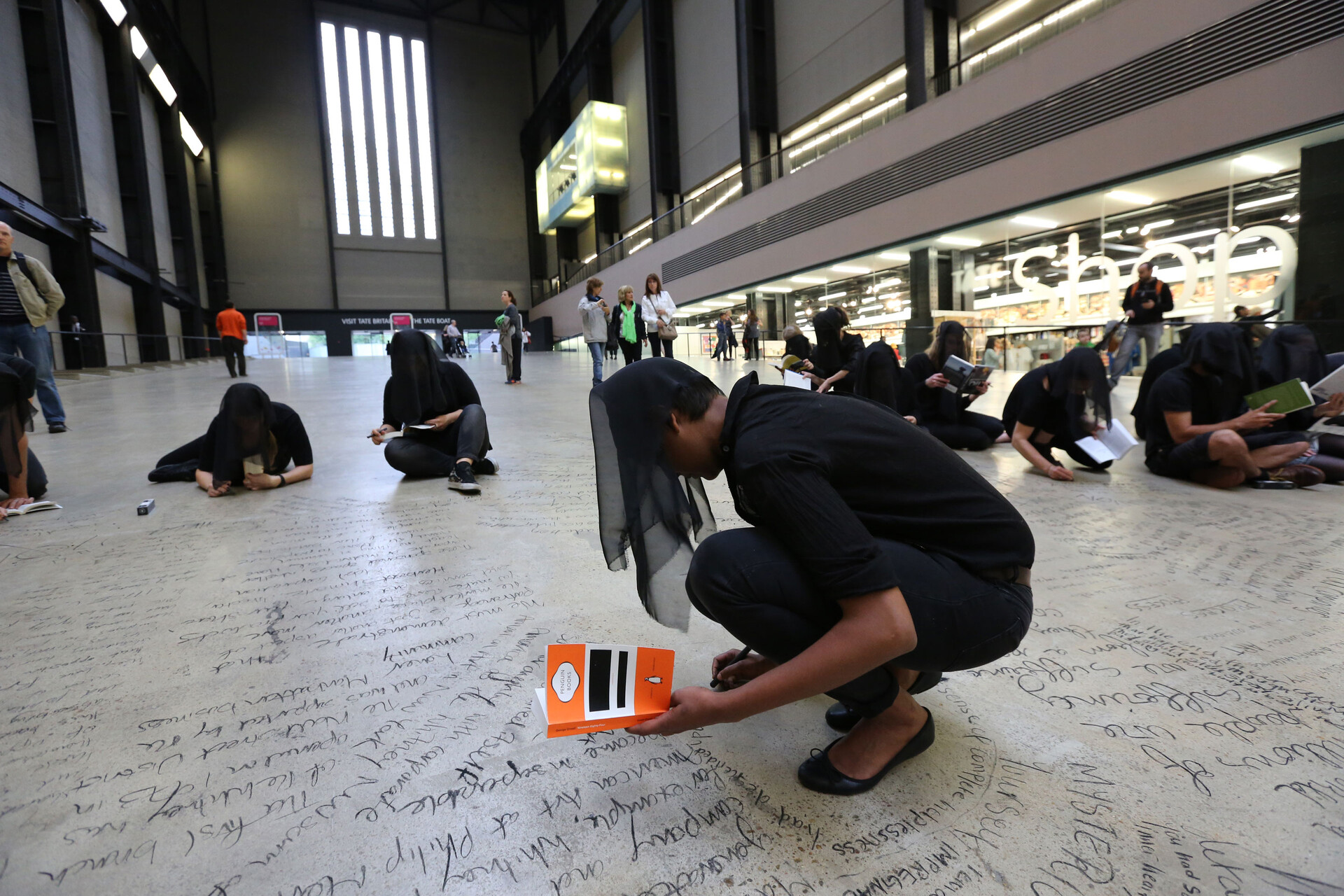

When The Natural History Museum was asked to participate, we invited a delegation of tribal leaders from across North America to take part in panels, roundtables, and luncheons around the question of how museums can support Native-led climate justice initiatives. We also used the conference to debut at CMNH “Kwel’ Hoy: We Draw the Line,” a three-year traveling exhibition and event series co-created with leaders from the Lummi Nation, a Coast Salish tribe from the Pacific Northwest that has been leading efforts to protect water and land in its region and around the country. At the center of this project is the Totem Pole Journey.

For the last six years, leaders from the Lummi Nation have transported a series of hand-carved totem poles along North American fossil fuel export routes to honor, unite, and empower communities working to protect water, land, and public health from the impacts of coal and oil transport. As the pole travels, it helps build alliances between Native and non-Native communities. In extending the Totem Pole Journey into CMNH, our aim was to engage the museum—and the museum public—as allies on the journey.

The exhibition featured video, audio, and interactive components, as well as the totem pole carved for the 2017 journey. The totem pole was displayed horizontally on a trailer as it traveled across the country, and visitors were invited to touch the pole and explore the stories about the red, black, white, yellow guardians of the Earth carved into its surface. It was paired with a participatory mobile mural painted by more than 140 Native and non-Native community members from cities and reservations along the journey’s route and coordinated by artist Melanie Schambach.

We also exhibited a series of Story Poles, vertically stacked shipping crates displaying objects selected by tribal leaders and community members living along the Totem Pole Journey route. From a sacred pipe used in ceremonies to a sample of coal ash from coal trains that have contaminated the Pacific Northwest’s Columbia River, the mix of objects in these displays were accompanied by audio interviews that conveyed the personal stories of climate justice and injustice that these items symbolized. Members of more than a dozen Native Nations helped develop the exhibition.

“Kwel’ Hoy: We Draw the Line” was intentionally placed in dialogue with “We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene,” the CMNH’s major exhibition on the Anthropocene. Within the conversation started by “We Are Nature,” our exhibition highlighted the communities that are working to protect water, land, and our collective future.

We also wanted to explore how an exhibition about fossil fuels and fossil fuel resistance could be staged in the heart of coal and fracking country, where the environmental impact of fossil fuels continues to be a contentious topic. By centering this project on the totem pole, a cultural artifact that one might expect to find in a museum of natural history, “Kwel’ Hoy” functioned like a Trojan horse, to paraphrase Lummi Tribal Councilman Freddie Lane. It helped us bring the Lummi campaign for a safe and sustainable future into the museum context.

The exhibition at CMNH represents only one stop in an evolving museum exhibition and public programming series that over the next three years will travel to the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian and other museums. Each exhibition will have the totem pole as its centerpiece but will be customized to include the host museum’s collections, the local Indigenous and frontline communities, and the climate and environmental justice issues that those communities face.

What Can Your Museum Do?

“Kwel’ Hoy” is as much a content-driven exhibition as it is a model for replication. We want to shine a spotlight on the many ways museums can participate in the climate and environmental justice movement, not only as advocates but also as supporters of communities that are leading the charge. Of course, every museum has its own specific mission, expertise, and operational limitations, but even the smallest institutions in the most conservative states can take real steps. Here are two possibilities:

1) Focus on the “just transition.” A common concern we hear from colleagues at peer institutions is that taking on environmental justice concerns in regions where fossil fuels are the bedrock of the local economy can make visitors feel alienated or attacked. What happens to their jobs, their homes, and their local economy when fossil fuels are abolished?

One of the most important concepts advanced by the climate justice movement is the notion of a “just transition” from a dirty energy economy to a clean energy economy. The climate justice framework plots an extensive plan in which nobody—including those currently employed by fossil fuel companies—is left behind. The discourse on just transition can help museums broach this topic with both decision-makers and visitors. Organizations such as Movement Generation offer age-appropriate trainings, workshops, and curricula on such climate justice concerns.

2) Partner with communities. The communities that are leading climate and environmental justice campaigns are using history, tradition, story, song, and distinct iconography in the context of their struggles. As trusted institutions, museums can lend their institutional support to these communities by contextualizing and uplifting their symbols, stories, struggles, and objects through exhibitions and public programs. They can only do this if they reach out, listen to, and work in partnership with the communities they want to support.

At many museums, increasing community engagement is now a top priority. Some, such as the Queens Museum in New York City, have hired full-time community organizers to broker relationships with historically underserved communities. Institutions that are unable to expand their operational capacity can reach out to grassroots networks such as the Climate Justice Alliance, Indigenous Environmental Network, and Native Organizers Alliance. The Natural History Museum is also able to facilitate collaborations between museums and communities that meet the needs of the various stakeholders involved.

A museum’s exhibitions, programs, outreach initiatives, and public statements need to underscore that environmental crises are also social crises, and that the climate disruption experienced today is a consequence of the exploitation of land and life everywhere. We need to challenge the perspective that nature is a commodity, and we need to elevate the alternative view that regards all things as relatives rather than resources to be extracted and sold for profit.

At the Totem Pole Blessing ceremony that opened the 2017 ICOM conference on the Anthropocene, Tsleil-Waututh Nation leader Rueben George asked how future generations will view the environmental decisions we have made. Referring to the totem pole, George explained, “This will represent that we did something. That we stood for something. That we said no to money, and we said yes to earth and air and water.”

The Totem Pole Journey has inspired so many to draw a line against the forces pushing us toward extinction. The Lummi and their allies invited museums to join them on the right side of history.

Beka Economopoulos is the director of The Natural History Museum.

“The Right Side of History: How can museums support Native-led climate justice initiatives?” was originally published in Museum (July/August 2018): 31-35.