Politics in the Anthropocene is a matter of perspective: we can’t look at climate change directly. Relying on multiple disparate measurements, we look for patterns and estimate probabilities. We see in parts: the melting ice caps, glaciers, and permafrost; the advancing deserts and diminishing coral reefs; the disappearing coastlines and the migrating species. Evidence becomes a matter of extremes as extremes themselves become the evidence for an encroaching catastrophe that has already happened: the highest recorded temperatures; the hockey stick of predicted warming, sea-level rise, and extinction. Once we see it—the “it” of climate change encapsulated into a data point or disastrous image—it’s already too late. But too late for what and for whom remains unsaid, unknowable. The challenge in this scenario becomes grappling with continuity. How can we conceive and wage the struggles already dividing the collectivity presumed in processes whose outcomes are estimated and predicted?

Climate change tethers us to a perspective that oscillates between the impossible and the inevitable, already and not yet, everywhere but not here, not quite. Slavoj Žižek reminds us that such oscillation indexes the “too much or too little” of jouissance. For psychoanalysis, particularly in Lacan’s teaching, jouissance is a special substance, that intense pleasure-pain of enjoyment that makes life worth living and some things worth dying for. We will do anything to get what we think we will enjoy. We then discover after we get it that it wasn’t what we really desired after all. Likewise, we try to discipline, regulate, and control enjoyment, only to find it emerging in another place. We get off even when we think we are trying not to. Jouissance is what we want but can’t get and what we get that we don’t want.

Some use climate change as a vehicle for jouissance, for enjoying destruction, punishment, and knowing. A current of left anthropocenic enjoyment circulates through evocations of unprecedented, unthinkable catastrophe: the end of the world, the end of the human species, the end of civilization. Theorists embrace extinction, focus on deep time, and displace a politics of the people onto the agency of things. Postmodern Augustinians announce the guilt or hypocrisy of the entire human species. Hubris is humanity’s, all of humanity’s, downfall. Philosophers and cultural critics take on the authoritative rhetoric of geoscientists and evolutionary biologists. Those of us who follow the reports of emissions, extreme weather, and failed states enjoy being in the know. We can’t do anything about climate change, but this lets us off the hook when we stop trying.

Getting to name our new era, marking our impact as the “Anthropocene,” provides a compensatory charge—hey, we changed the world after all. Even better than coming up with a name for our era is the jouissance that comes from getting to judge everyone else for their self-absorbed consumerist pleasures—why didn’t you change when you should have? Anticipatory Cassandras, we watch from within our melancholic “pre-loss,” to use Naomi Klein’s term, comforted by the fantasy of our future capacity to say we knew it all along. We told you so. Your capitalism, instrumental reason, or Cartesian dualism killed us all. Or so we fantasize, screening out the unequal distribution of the effects of warming—Russia doesn’t worry about it as much as, say, Bangladesh.

The perfect storm of planetary catastrophe, species condemnation, and paralyzed incapacity allows the Left a form of jouissance that ongoing deprivation, responsibility, and struggle do not allow. Overlooked as too human, these products and conditions of capitalism’s own continuity can be dismissed as not mattering, as immaterial. Organized political movement appears somehow outmoded, its enduring necessity dispersed into individuated ethico-spiritual orientations on a cosmos integrated over eons.

This left anthropocenic enjoyment of destruction, punishment, and knowing circulates in the same loop as capitalist enjoyment of expenditure, accumulation, and waste, an enjoyment furthered by fossil fuels, but not reducible to them. Left anthropocenic enjoyment thrives on the disaster that capitalist enjoyment produces. In this circuit, captivation in enjoyment fuels the exploitation, expropriation, and extraction driving the capitalist system: more, more, more; endless circulation, dispossession, destruction, and accumulation; ceaseless, limitless death. Incapacitated by magnitude, boggled by scale, the Left gets off on moralism, complexity, and disaster—even as the politics of a capitalist class determined to profit from catastrophe continues.

The circulation of left anthropocenic enjoyment through capitalist currents manifests in a diminished capacity for imagining human subjectivity. Even as things, objects, actants, and the nonhuman engage in a wide array of lively pursuits, the anthropocenic perspective seems to confine humans to three roles: observers, victims, and survivors. Observers are the scientists, their own depression and loss now itself a subgenre of climate writing. Scientists measure and track, but can’t do anything about the unfolding catastrophe—action is for others. Observers also appear as the rest of us as moral audience, enjoined to awareness of human-nonhuman entanglements and the agency of microbes. In this vein, our awareness matters not just as an opportunity for spiritual development but also because multiple instances of individuated moral and aesthetic appreciation of fragility and the limits of human agency could potentially converge, seemingly without division and struggle. When the scale is anthropocenic, the details of political organization fall away in favor of the plurality of self-organizing systems. The second role, victims, points to islanders and refugees, those left with nothing but their own mobility. They are, again, shorn of political subjectivity, dwarfed by myriad other extinctions, and reduced to so much lively matter. The third role is as survivors. Survivors are the heroes of popular culture’s dystopic futures, the exceptional and strong concentrations of singular capacity that continue the frontiersmanship and entrepreneurial individualism that the US uses to deny collective responsibility for inequality. I should add here that Klein’s most significant contribution with This Changes Everything is her provision of the new, active, collective figure of “Blockadia.” As is well-known, Blockadia designates organized political struggles against fracking, drilling, pipelines, gas storage, and other projects that extend the fossil fuel infrastructure when it should in fact be dismantled. With this figure, Klein breaks with the anthropocenic displacement of political action.

If fascination with climate change’s anthropocenic knot of catastrophe, condemnation, and paralysis lures the Left into the loop of capitalist enjoyment, an anamorphic gaze can help dislodge us. “Anamorphosis” designates an image or object that seems distorted when we look at it head on, but that appears clearly from another perspective. A famous example is Hans Holbein’s 1533 painting The Ambassadors, in which a skull in the painting appears as such only when seen from two diagonal angles; viewed directly, it’s a nearly indistinguishable streak. Lacan emphasizes that anamorphosis demonstrates how the space of vision isn’t reducible to mapped space but includes the point from which we see. Space can be distorted, depending on how we look at it. Apprehending what is significant, then, may require “escaping the fascination of the picture” by adopting another perspective—a partial or partisan perspective, the perspective of a part. From this partisan perspective, the whole will not appear as a whole. It will appear with a hole. The perspective from which the hole appears is that of the subject, which is to say of the gap opened up by the shift to a partisan perspective.

When we try to grasp climate change directly, we end up confused, entrapped in distortions that fuel the reciprocal fantasies of planetary scale geoengineering and post-civilizational neo-primitivism. The immensity of the calamity of the changing climate—with attendant desertification, ocean acidification, and species loss—seemingly forces us into seeing all or nothing. If we don’t grasp the issue in its enormity, we miss it entirely. In this vein, some theorists insist that the Anthropocene urgently requires us to develop a new ontology, new concepts, new verbs, entirely new ways of thinking, yet I have my doubts: geologic time’s exceeding of human time makes it indifferent even to a philosophy that includes the nonhuman. If there is a need, it is a human need implicated in politics and desire, that is to say, in power and its generation and deployment.

The demand for entirely new ways of thinking comes from those who accept as well as those who reject capitalism, science, and technology. “Big thinkers” in industry and economics join speculative realists and new materialists in encouraging innovation and disruption. Similarly, the emphasis on new forms of interdisciplinarity, on breaking down divisions within the sciences and between the sciences and the humanities isn’t radical, but a move that has been pursued in other contexts. Modern environmentalism, as Ursula Heise observes, tried to “drive home to scientists, politicians, and the population at large the urgency of developing a holistic understanding of ecological connectedness.”[1] The Macy Conferences that generated cybernetics and the efforts of the Rand Corporation and the Department of Defense to develop more flexible, soft, and networked forms of welfare, as well as contemporary biotech, geotech, and biomimicry, all echo the same impulse to interlink and merge.

The philosopher Frédéric Neyrat has subjected the “goosphere” that results from this erasure of spacing to a scathing critique, implicating it in the intensification of global fears and anxieties: when everything is connected, everything is dangerous. Neyrat thus advocates an ecology of separation: the production of a “distance within the interior of the socio-political situation” is the “condition of possibility of real creative response to economic or ecological crisis.”[2] Approaching climate change anamorphically puts such an ecology of separation to work. We look for and produce gaps. Rather than trapped by our fascination with an (always illusory) anthropocenic whole, we cut across and through, finding and creating openings. We gain possibilities for collective action and strategic engagement.

Just as it inscribes a gap within the supposition of ecological connectedness, the anamorphic gaze likewise breaks with the spatial model juxtaposing the “molar” and the “molecular” popular with some readers of Deleuze and Guattari. Instead of valorizing one pole over the other (and the valued pole is nearly always the molecular, especially insofar as molecular is mapped onto the popular and the dispossessed rather than, say, the malignant and the self-absorbed), the idea of an anamorphic perspective on climate change rejects the pre-given and static scale of molar and molecular to attend to the perspective that reveals a hole, gap, or limit constitutive of desire and the subject of politics.

Here are some examples of approaching climate change from the side. In Tropics of Chaos, Christian Parenti emphasizes the “catastrophic convergence” of poverty, violence, and climate change. He draws out the uneven and unequal impacts of planetary warming on areas already devastated by capitalism, racism, colonialism, and militarism. From this angle, policies aimed at redressing and reducing economic inequality can be seen as necessary for adapting to a changing climate. In a similar vein but on a different scale, activists focusing on pipeline and oil and gas storage projects target the fossil fuel industry as the infrastructure of climate change, the central component of global warming’s means of reproduction. But instead of being examples of the politics of locality dominant in recent decades, infrastructure struggles pursue an anamorphic politics. They don’t try to address the whole of the causes and effects of global warming. They approach it from the side of its infrastructural supports. The recent victory of the campaign against the Keystone Pipeline, as well as of the anti-fracking campaign in New York State, demonstrate ways that an anamorphic politics is helping dismantle the power of the oil and gas industry and produce a counterpower infrastructure.

The new movement to liberate museums and cultural institutions from the fossil fuel sector supplies a third set of examples, modeling a politics that breaks decisively with the melancholic catastrophism enjoyed by the anthropocenic Left. As the demonstrations at the Louvre accompanying the end of the Paris COP made clear, artists and activists have shifted their energy away from the promotion of general awareness and participation to concentrate instead on institutions as arrangements of power that might be redeployed against the oil and gas industry. Pushing for a fossil-free culture, an array of groups have aligned in a fight against the sector that supplies capitalism with its energy. They demonstrate how the battle over the political arrangement of a warming planet is in part a cultural battle, a struggle over who and what determines our imagining of our future and the future of our imagining.

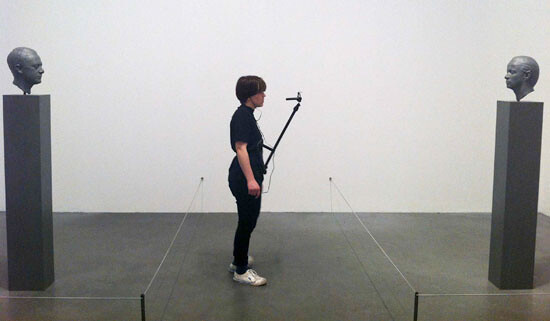

In this vein, Liberate Tate works to free art from oil by pushing the Tate to drop the sponsorship of British Petroleum. For the past five years, the group has performed art interventions in Tate buildings as well as other UK arts institutions that support (and are supported by) BP. Actions include unauthorized performances such as Birthmark, from late November 2015. Liberate Tate activists occupied the 1840s gallery at the Tate Britain, tattooing each other with the number of C02 emissions in parts per million corresponding to the day they were born. Hidden Figures, from 2014, featured dozens of performers standing along the sides of a hundred-square-meter black cloth which they held chest high, raising and lowering in arches and waves. Taking place in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, the performance pointed to Malevich’s Black Square, part of an exhibit that opened the same summer that carbon concentrations exceeded four hundred parts per million, a fact parallel to and omitted from the exhibit, much like BP’s—and by implication the Tate’s—involvement in the climate crisis. Hidden Figures invokes the Tate’s release of the minutes of meetings from its ethics committee in the wake of numerous freedom of information requests. Black rectangles blocked out multiple sections of the released documents. Hidden Figures reproduced an enormous black square within the museum, placing the fact of redaction, hiding, and censorship at its center. As Liberate Tate explains, the redactions reveal a divide, a split between the ostensible public interest of the Tate and the private interest it seeks to protect.[3] Occupying this split via its demonstration of the museum’s incorporation into BP’s ecocidal infrastructure, Liberate Tate disrupts the flow of institutional power. Rather than fueling BP’s efforts at reputation management, it makes the museum into a site of counterpower.

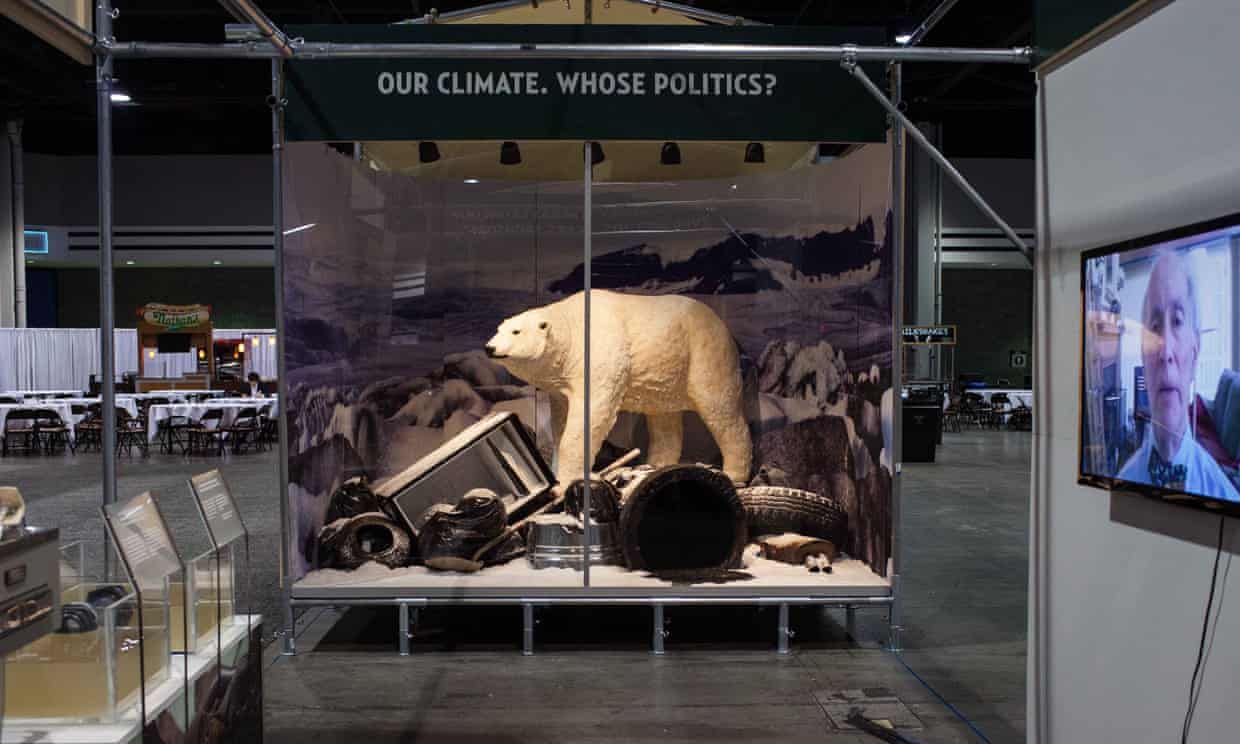

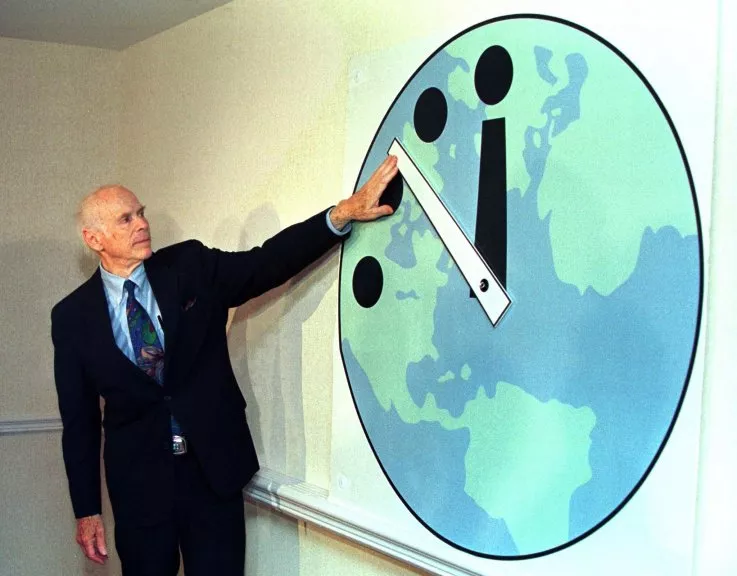

The Natural History Museum, the new project of the art, activist, and theory collective Not An Alternative (of which I am a member), similarly adopts an anamorphic politics. The Natural History Museum repurposes the generic form of the natural history museum as a set of institutionalized expectations, meanings, and practices that embody and transmit collective power. It puts display on display, transferring our attention to the infrastructures supporting what and how we see. The Natural History Museum’s gaze is avowedly partisan, a political approach to climate change in the context of a museum culture that revels in its authoritative neutrality. Activating natural history museums’ claim to serve the common, The Natural History Museum divides the sector from within: anyone tasked with science communication has to take a stand. Do they stand with collectivity and the common or with oligarchs, private property, and fossil fuels? Cultural institutions such as science and natural history museums come to appear in their role in climate change as sites of greenwashing and of emergent counterpower.

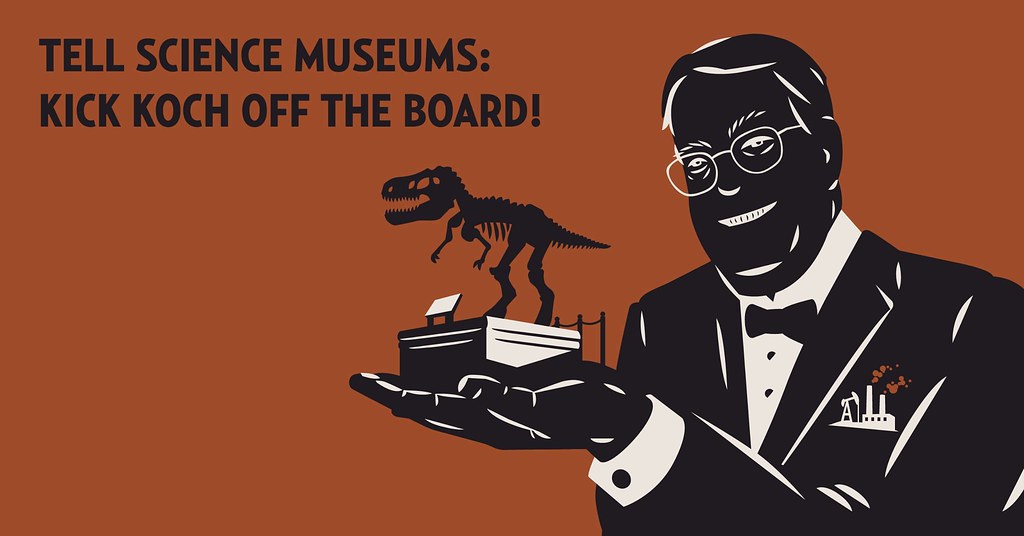

Operating as a pop-up people’s museum, The Natural History Museum’s exhibits and tours provide a counter-narrative that combats the influence oil and gas industry on science education. The Natural History Museum also serves as a platform for political organizing, the ostensibly neutral zone of the museum turned into a base camp against the fossil fuel sector. It moves beyond participatory art’s creation of experiences and valuation of participation for its own sake to the building of divisive political power. In March 2014, The National HistoryMuseum released an open letter to museums of science and natural history signed by dozens of the world’s top scientists, including several Nobel laureates. The letter urged museums to cut all ties with the fossil fuel industry and with funders of climate obfuscation. After its release, hundreds of scientists added their names. News of the letter appeared on the front pages of the New York Times, Washington Post, and LA Times and featured in scores of publications, including the Guardian, Forbes, Salon, and the Huffington Post. Later that spring, The Natural History Museum delivered a petition with over 400,000 signatures to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC demanding that the museum kick fossil fuel oligarch David Koch off its board.

The premise of Liberate Tate and Not An Alternative is that institutions matter as combined and intensified expressions of power. More than just the aggregation of individuals, they are individuals plus the force of their aggregation. Because institutions remain concentrations of authority that can be salvaged and put to use, it makes political sense to occupy rather than ignore or abandon them. We can repurpose trusted or taken-for-granted forms—a possibility precluded by the anthropocenic preoccupation with an imaginary whole figured in geologic time. Just as the museum is a site in the infrastructure of capitalist class power—with its donors and galas and named halls—so can it be a medium in the production of a counterpower infrastructure that challenges, shames, and dismantles the very class and sector that would use what is common for private benefit.

The movement to liberate museums and cultural institutions from fossil fuel interests does not try to present climate change directly or nature as a whole. Instead, it approaches the processes contributing to global warming as processes in which we are already implicated. We are within the systems and institutions the effects of which scientists measure and chart. And that the people as the collective subject of politics are in them means that they are not fully determined. There are gaps that we can hold open and force in one direction rather than another. In too many contemporary discussions of the Anthropocene, the organization of people—our institutions, systems, and arrangements of power, production, and reproduction—appears only as a distortion. Everything is active except for us, we with no role other than that of observers, victims, or lone survivors. In contrast with emphases on nonhumans, actants, and distributed agency, the strategic coming together of organized opposition to the fossil fuel sector points to the continued and indispensable role of collective power. Just as a class politics without ecology can support extractivism, so can an ecology without class struggle continue the assault on working people that has resulted in deindustrialization in parts of the North and West and hyperindustrialization in parts of the South and East (we might call such an ecology without class struggle “green neoliberalism”). So we shouldn’t undermine collective political power in the name of a moralistic horizontalism of humans and nonhumans. We should work to generate collective power and mobilize it in an emancipatory egalitarian direction, a direction incompatible with the continuation of capitalism and hence a direction necessarily partisan and divisive.

Jodi Dean is Professor of Political Science at Hobart and William Smith Colleges and Erasmus Professor of the Humanities in the Faculty of Philosophy at Erasmus University. She is the author or editor of nine books. The most recent is Democracy and Other Neoliberal Fantasies: Communicative Politics and Left Politics.

- [1]Ursula Heise, Sense of Place and Sense of Planet (Oxford University Press, 2008), 22.↩

- [2]Frédéric Neyrat, “Economy of Turbulence: How to Escape from the Global State of Emergency?” Philosophy Today 59, 4 (Fall 2015):657–669.↩

- [3]Liberate Tate, “Confronting the Institution in Performance,” Performance Research 20.4 (2015): 78–84.↩