The Anamorphic Politics of Climate Change

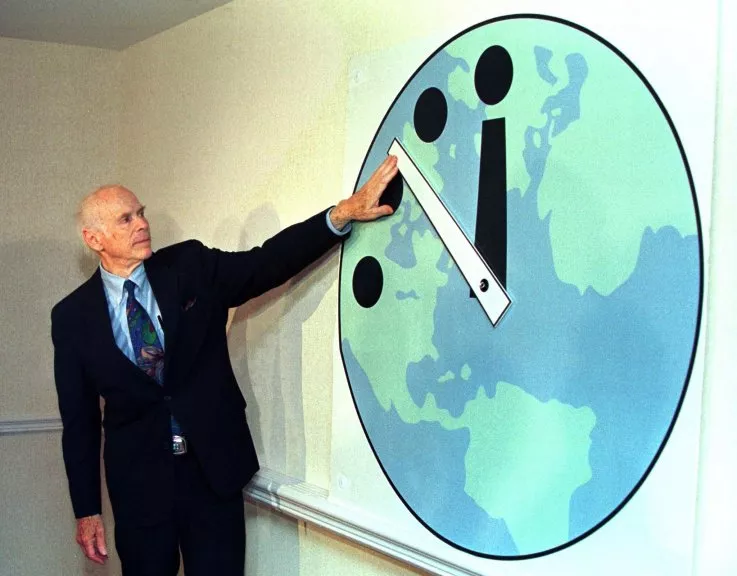

The challenge of politics in the Anthropocene is a matter of perspective: we can’t look at climate change directly. We look for patterns and estimate probabilities, relying on multiple disparate measurements. We see in parts: the melting ice caps, glaciers, and permafrost; the advancing deserts and diminishing coral reefs; the disappearing coastlines and the migrating species. Evidence becomes a matter of extremes as extremes themselves become evidence of an encroaching catastrophe that has already happened: the highest recorded temperatures, the hockey stick of predicted warming, sea-level rise, and extinction. Once we see it—the “it” of climate change encapsulated into a data point or disastrous image—it’s too late. For what and for whom remains unsaid, unknowable.[1]

Climate change tethers us to a perspective that oscillates between the impossible and the inevitable, already and not yet, everywhere but not here, not quite. Slavoj Zizek reminds us that such oscillation indexes the “too much or too little” of enjoyment (jouissance). For psychoanalysis, particularly in Lacan’s teaching, enjoyment is a special substance, that intense pleasure/pain that makes life worth living and some things worth dying for. We will do anything to get what we think we will enjoy. We then discover after we get it that it wasn’t what we really desired after all. Enjoyment is what we want but can’t get and what we get that we don’t want.[2]

Currents of Left anthropocenic enjoyment circulate via evocations of unprecedented, unthinkable catastrophe: the end of the world, the end of the human species, the end of civilization.[3] Prophetic Cassandras condemn all around them for our profligacy, even as they imply that there isn’t anything we can do. The damage has already been done. The perfect storm of planetary catastrophe, species condemnation, and paralyzed incapacity lets the Left enjoy in ways that ongoing deprivation, responsibility, and struggle do not. Left anthropocenic enjoyment thereby feeds on the disaster capitalist enjoyment produces. More, more, more; endless circulation, dispossession, destruction, and accumulation; ceaseless, limitless death. Incapacitated by magnitude, boggled by scale, the Left gets off on moralism, complexity, and disaster—even as politics continues, the politics of a capitalist class determined to profit from catastrophe.

If fascination with climate change’s anthropocenic knot of catastrophe, condemnation, and paralysis lures the Left into the loop of capitalist enjoyment, an anamorphic gaze can help dislodge us. “Anamorphosis” designates an image or object that seems distorted when we look at it head on but that appears clearly from another perspective. Jacques Lacan (1998) emphasizes that anamorphosis demonstrates how the space of vision isn’t reducible to mapped space. It includes the point from which we see. Space can be distorted, depending on how we look at it. Apprehending what is signiWcant, then, may require “escaping the fascination of the picture” by adopting another perspective, a partial or partisan perspective, the perspective of a part. From a partisan perspective, the whole will not appear as a whole. It will appear with a hole. The perspective from which the hole appears is that of the subject—that is, of the gap that the shift to a partisan perspective opens up.

When we try to grasp climate change directly, we trap ourselves in distortions that fuel the reciprocal fantasies of planetary-scale geoengineering and postcivilizational neoprimitivism. The immensity of the calamity of the changing climate—with attendant desertiWcation, ocean acidiWcation, and species loss—seemingly forces us into seeing all or nothing. If we don’t grasp the issue in its enormity, we miss it entirely. When we approach climate change indirectly, from the side, however, other openings, political openings, become visible. Rather than being ensnared by our fascination with an illusory anthropocenic whole, we cut across and through, gaining possibilities for collective action and strategic engagement.

Here are some examples of approaching climate change from the side. Christian Parenti (2011) emphasizes the “catastrophic convergence” of poverty, violence, and climate change. He draws out the uneven and unequal impacts of planetary warming on areas already devastated by capitalism, racism, colonialism, and militarism. From this angle, policies aimed at redressing and reducing economic inequality appear as necessary adaptations to a changing climate. In a similar vein, but on a different scale, activists focused on pipeline and oil and gas storage projects target the fossil fuel industry as the infrastructure of climate change, the central component of warming’s means of reproduction. Instead of exemplifying a tired politics of locality, infrastructure struggles pursue the anamorphic politics of climate change. They don’t try to address the whole of the causes and effects of global warming. They approach it from the side, the side of its infrastructural supports.

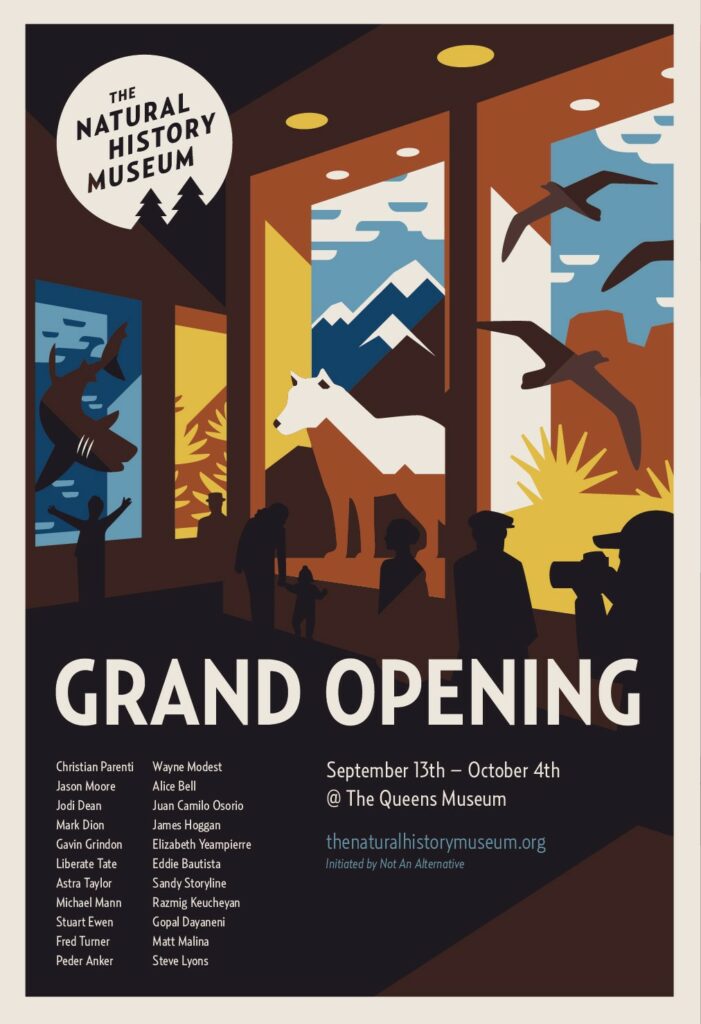

The NHM, the new project of the art, activist, and theory collective Not An Alternative, likewise pursues an anamorphic politics. In this ongoing performance, Not An Alternative adopts the legitimating aesthetics, pedagogical models, and presentation forms of natural history museums in support of a divisive perspective on science, nature, and capitalism. With the NHM, Not An Alternative does not try to present climate change directly or nature as a whole. Instead, the project approaches our setting from the side, through examinations of labor history, social movements, public relations, and practices of science communication. The NHM puts displays on display, transferring our attention to the infrastructures supporting what and how we see. Its anamorphic gaze is avowedly partisan, a political approach to climate change in the context of a museum culture that revels in its “authoritative neutrality.” The NHM activates the natural history museum’s claim to serve the common, thereby dividing the museum from within: anyone connected to the museum sector, anyone tasked with communicating science and natural history to a wider public, has to take a side. Do they stand with collectivity and the common or with oligarchs, private property, and the fossil fuel industry?

This essay focuses on the innovative artistic and political practice evinced by the NHM. I situate the project in Not An Alternative’s work as politically engaged artists, attending to some of the ways the NHM responds to problems that arise in the overlap of socially engaged art and institutional critique, understanding this response as lessons for politics in the Anthropocene.[4] The NHM is, first, a platform for political organizing that treats the museum, science, and nature as sites of struggle. As a platform, the NHM moves beyond socially engaged art’s creation of experiences and valuation of participation for its own sake to function as an organizing tool for building divisive political power. The NHM, second, is an artistic project that confiscates the form of the natural history museum in order to direct us toward what the museum as an institution excludes—namely, the place of power and politics in determining how we see and what is possible. Extending institutional critique (work from artists such as Hans Haacke, Fred Wilson, Mark Dion, and Andrea Fraser), the NHM locates the limits to a system within the system. The repercussion is that working within a system becomes not cooptation and complicity but occupation and seizure. Consequently, third, the NHM is a theoretical laboratory for experiments in seizing the state by seizing the institutions that transmit knowledge and legitimacy—experiments, in other words, in the building of a counterpower infrastructure. The wide array of operations that constitute the project demonstrate a capacity for political organization and strategy, one the can be adopted, amplified, and extended. In fact, Not An Alternative’s NHM is a project that shares with other recent projects an emphasis on the politics of the institution: for example, Jonas Staal’s New World Summit and Liberate Tate’s efforts to liberate cultural institutions from the oil industry, specifically BP. In contrast with Left anthropocenic enjoyment of failure, moralism, and catastrophe, lessons in institutionality hold open the promise of and need for collective struggle.

Too many contemporary discussions of the Anthropocene so obscure the organization of people—our institutions, systems, and arrangements of power, production, and reproduction—that they appear only as distortions. Everything is active except for us. In contrast with emphases on nonhumans, actants, and vibrant matter, I am interested in the political subject as it registers in the gap between the haste of an action and the retroactive determination of this precipitous act as the act of a collective political subject.[5] We shouldn’t undermine collective political power in the name of a moralistic horizontalism of humans and nonhumans. We should work to generate collective power and mobilize it in an emancipatory egalitarian direction, a direction incompatible with the continuation of capitalism and hence a direction necessarily partisan and divisive. The NHM, along with other projects of institutional liberation, pushes the imagining, production, and organization of such a power in the context of the resource struggles of the Anthropocene. Through their work, the people appear with a capacity to effect political change.

Institutionality, at a Minimum

As is clear from its name, Not An Alternative twists Margaret Thatcher’s infamous “there is no alternative” to shift from something in the negative to nothing in the positive. This “nothing” is an interior antagonism, an object’s nonidentity with itself, the inherent limit of a system, or the gap constitutive of the subject. Not An Alternative’s projects aim to find and occupy the impossible instances of a given system, splitting the system by forcing its internal limits back onto it and seizing the common, egalitarian potential that is already present.[6] Forcing of a lack opens the space of the subject; seizing the common demonstrates fidelity to the people as that subject.

Not An Alternative developed its position in part via a critique of communicative capitalism—more specifically, via a critique of the injunction to participate that infuses the contemporary intertwining of democracy and capitalism. In a context where activists and artists were repeating communicative capitalism’s demand for participation as if participation were in and of itself a radical or emancipatory act, Not An Alternative emphasized how networked media involves us in building the traps that ensnare us. The group explains, “We come up with new forms and they are integrated directly as fuel for a system that is fundamentally unsustainable. Our solutions are sucked into the brand identities of institutions. As Not An Alternative, we are not interested in the production of solutions or the inclusion of new subjectivities or symbols, but rather the excavation and occupation of existing ones, revealing an inherent split” (Donovan). Under conditions of the proliferation of memes and images, of capitalist efforts to identify and monetize whatever is new and different and intense competition for positions, recognition, and capital, producing the new feeds the system. In the name of democratic participation, artists and activists end up reinforcing dominant processes of multiplication and diffusion.[7] Treating democracy as the value to be realized, they proceed as if politics were nothing more than social engagement. The role of the artist then becomes creating new openings through which people might engage and be engaged. Not An Alternative breaks with socially engaged art in that it views politics antagonistically. Political art should occupy division and force the institution to take a side.

Not An Alternative’s work takes the form of installations, interventions in arts institutions and public spaces, and political collaborations. Collaborations have been with community groups (for example, Occupy Sandy and Picture the Homeless, a housing advocacy group in NYC), activist campaigns (Strike Debt), and social movements (Occupy Wall Street, antiforeclosure, climate justice). In these collaborations, Not An Alternative has two aims: to find the limits of a given system and to assemble a symbolic infrastructure that links groups and actions, making disparate actions and campaigns legible as fronts in one struggle. So even as Not An Alternative’s work stretches from video and performance, through museums and urban spaces, to research and organizing, it is marked by what Yates McKee (2013) calls a “militant uniformity.” This militant uniformity comes from the common, the visual systems that continue to signify some minimal degree of institutionality in our setting of the decline of symbolic efficiency.

Not An Alternative came up with Occupy’s black-and- yellow symbolic infrastructure (McKee 2014). This infrastructure takes the color scheme and style associated with public works such as construction sites and highway caution signage and puts it in the hands of the people. With this visual infrastructure, Not An Alternative presented the occupation in terms of what was common: common tactics carried out under a name in common. Rather than a marker left by capitalism and the state, the signage points to the common interest of the people, to the division they share in common. When activists reappropriate warning tape and caution signage, they force the question: in whose interest is power exercised? During Occupy, the “militant uniformity” of the yellow and black helped make a collective subject present to itself, enabling it to feel itself as a collective force.

Likewise, in contrast with the familiar critique of representation, Not An Alternative demonstrated the power of representation.[8] It pulled out a visual element of the movement—tents— forcing acknowledgement of the way tents already functioned as clear symbols of occupation. Where various activist, artistic, and theoretical voices reject representation for its inevitable omissions, a rejection anchored in the fantasy of a pure, complete, and direct representation, a fantasy of absolute and unmediated inclusion, Not An Alternative recognizes that representations attempt to produce their subjects (Steyerl, 17).[9] A shared image or point of identification, a name in common, affects those who identify it as a marker of collectivity—whether they identify with it as their own or see it as designating an enemy. Because of Occupy, tents assumed a political meaning that had remained implicit in their range of appearings in refugee camps and the temporary encampments that sprung up outside U.S. cities in the economic downturn. People were asserting themselves in places where they did not belong, refusing to accept any longer the barriers posed by capital and the state. Whether or not every occupier was actually living in a tent, tents signified occupation, pressing the divisive claim of the people against the one percent. Not An Alternative’s “mili-tents,” carried in actions and attached to walls even after police had cleared all the occupiers out of Zuccotti Park, both pointed to the fundamental division in capitalism that Occupy asserted and highlighted the symbolic infrastructure the movement itself was producing.

Not An Alternative’s practice is situated in the overlap between socially engaged art and “institutional critique.” Initially appearing at the end of the 1960s, institutional critique has gone through two and arguably even three waves.[10] Given current discussion of these waves, it is perhaps most accurate to locate Not An Alternative’s practice in the critique of institutional critique that emerged in the second and third waves in the 1990’s and 2000’s; to locate it, in other words, in institutional critique’s own self-reflection.

The first wave of institutional critique developed an immanent critique of the institution of art, applying to museums normative criteria that the museums themselves claimed to hold. Crucial to this critique was the exposure not simply of the market dimension of art but of the role of class in determining what counts as art and the role of art in establishing the signifiers of class.[11] Artists such as Hans Haacke, a key influence on Not An Alternative, extended the idea of the “institution” beyond spaces for the teaching, viewing, production, and selling of art to encompass “the network of social and economic relationships between them” (Fraser, 412).

The second wave of institutional critique focused on the limits of institutional critique. Did institutional critique’s dependence on the institution it was critiquing in some way compromise it, making it just as guilty and complicit as the gallery or museum? Did attempts to find loci of independence backfire when an institution happily sponsored “external” critical perspectives as aesthetic events from which the institution itself was critically shielded or immunized, its political credentials established by the fact of its sponsorship? As Fraser argues in her influential 2006 essay, “It is artists—as much as museums or the market— who, in their very efforts to escape the institution of art, have driven its expansion. With each attempt to evade the limits of institutional determination, to embrace an outside, to redefine art or reintegrate it into everyday life, to reach ‘everyday’ people and work in the ‘real’ world, we expand our frame and bring more of the world into it. But we never escape it” (414). Inclusion in the institution serves as the very means by which political effects are precluded, deactivated. Expanding the frame spreads political deactivation. Once everything is art, included within and supporting the institutional frame, nothing is political.

Not An Alternative accepts Fraser’s point that escape is impossible— there is no outside. With Lacanian theory as an explicit part of its practice, Not An Alternative locates the limit within the institution.[12] No institution is fully self-identical. Institutions are split between the ideals they espouse and their actual practices, between the practices they openly acknowledge and the obscene rituals they have to deny. Not An Alternative thus turns the institution against itself, siding with its better nature, and forcing others to take a side. It looks for allies, “double agents” already working within the institution, reinforces them, and in so doing activates the power that is already there. So rather than just making complicity with state and capital visible, Not An Alternative treats institutions as forms to be seized and connected into a counterpower infrastructure. Fraser writes, “It’s not a question of being against the institution: We are the institution. It’s a question of what kind of institution we are, what kind of values we institutionalize, what forms of practice we reward, and what kinds of rewards we aspire to” (416). Emphasizing the “we,” Fraser points to the necessity of a partisan position. Not just any values, and certainly not all values, are politically compatible with the institution “we” are. The institution is the site of a larger struggle, a territory or apparatus that can be commandeered.

This is the overlap between Not An Alternative’s critique of participation and its institutional critique. In each case it emphasizes the importance of division, taking a side. Not An Alternative rejects the supposition of some socially engaged art that the goal is creative experience and inclusive participation. Instead, it embraces militant opposition, tight organizational forms, and the aggregated power of institutions. It insists as well on the struggle that continues within any group, form, or institution. Division goes all the way down. Self-identity is a fantasy. Not An Alternative further rejects both the melancholic claims of contemporary depoliticization and a politics thought in terms of resistance, insurrection, playful aesthetic disruptions, and the establishment of momentary relations of community and belonging. It aims to occupy institutions, build counterpower infrastructure, and develop strategies. Not An Alternative rejects familiar calls for innovation. Instead, it salvages the generic images, practices, institutions, and forms that have already compiled and stored collective power. Here it claims the continued power of communism as the name for an anticapitalism oriented toward the collective desire for collectivity.

To sum up, for Not An Alternative, institutions are sites of collective power. It models a Leninist strategy for seizing the state under conditions of communicative capitalism as it takes over available signifying modes and reclaims the communicative common of language, ideas, knowledge, and affects. This is a politics of organization, infrastructure, and counterpower. To the extent that Not An Alternative’s projects do not simply create momentary social relations or open participatory social spaces but actually build a partisan counterpower infrastructure, their work moves beyond socially engaged art to the art of political engagement; an art that, no longer confined with the suppositions of a democratic imaginary, takes communism as its horizon.

Being the Museum

Not An Alternative’s current multiyear project, the NHM, employs the visual and communicative practices of natural history museums to perform a sort of “people’s natural history”—that is to say, a natural history that includes the struggles of the oppressed and laboring classes. Instead of relying on aesthetic gestures of critique, irony, or the retreat into poetic reverie found in some ecological art, Not An Alternative takes on the generic form of the natural history museum. Becoming the institution allows it to incorporate sincerity, commitment, partisanship, and truth into a politically engaged artwork. The NHM isn’t a joke or a stunt. It’s a registered member of the American Alliance of Museums. It has a board that includes prominent scientists (James Powell), artists (Mark Dion), and environmental activists (Naomi Klein). It doesn’t exist as a building. It exists as an insistent collective perspective on the common.

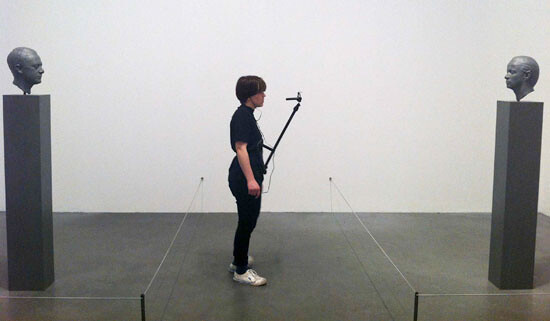

As an artistic project, the NHM installs a gap between the expectations associated with the natural history museum form and its own displays. These include re-creations of dioramas from other natural history museums as well as letters, petitions, campaigns, articles, and events authorized by the museum. By exhibiting how nature appears, the NHM opens up not only the irreducibility of nature to its appearing but also the gap of human systems, perceptions, and institutions within nature. This gap forces “visitors” (whether construed as the specific museum professionals addressed in some exhibitions and organizing efforts or more broadly as anyone who comes in contact with the name “Natural History Museum”) to acknowledge the place from which they see.

The museum as an institution works allegorically as a screen through which to access the real of political antagonism occluded in the moralizing and technocratic discourses of the Anthropocene. A natural history museum is a collective perspective on a common world. Visitors to the NHM encounter themselves as a collective in their act of looking: how does the common appear in this institution dedicated to fostering appreciation of the natural world, and how is what is common excluded? With this reflexive torsion, the NHM holds open the gap it installs, politicizing it as a collective desire for collectivity.

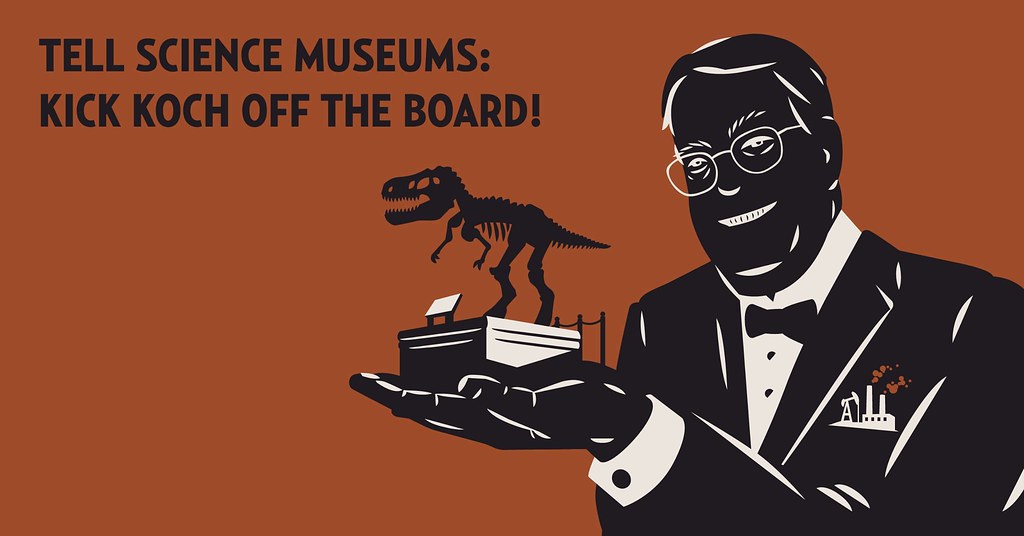

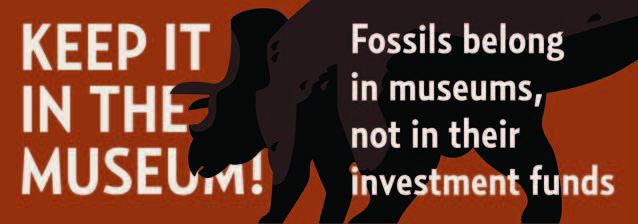

The NHM functions as a campaign and counterinstitution. As a political campaign, it challenges fossil fuel industry greenwashing in natural history museums. Here it provides a platform for calls for fossil fuel divestment. The NHM’s speciWc targets are the cultural institutions that communicate knowledge of science and nature: museums that retain a great deal of public trust but which provide legitimating opportunities for coal, oil, and gas companies. Fossil fuel oligarchs like David R. Koch sit on the boards of and are major donors to such influential museums as the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. The dinosaur wing in the American Museum of Natural History, for example, is named after Koch, who donated twenty million dollars to the museum. To combat this oligarchic influence, the NHM organizes scientists, museum workers, and museum visitors to stand with and for the common over and against capitalist extraction, exploitation, and expropriation.

Although it does not have a permanent brick-and- mortar (or steel-and- glass) base, the NHM does have a bus. It uses the bus for expeditions to sites such as Sunset Park, Brooklyn, an area within New York City’s storm surge zone; eleven oil wells in the Big Cypress National Reserve in the Florida swampland; and Washington, D.C., for the delivery of a petition with over four hundred thousand signatories demanding that the Smithsonian Institute remove Koch from its board.[13] Reports of the NHM’s expeditions appear regularly on its website.

Launched to coincide with the People’s Climate March, the NHM opened in September 2014 with an exhibition and discussion series in the New York City building at the Queens Museum. The NHM’s opening exhibition was set inside a sixty-four- foot tent inside the building. It featured a series of light boxes with photographs of dioramas from various natural history museums. The diorama is the aesthetic form most associated with the twentieth-century natural history museum. It doesn’t attempt to impart information so much as it tries to convey feelings of wonder. Its romantic, idealized, and hyperrealistic displays bring the aura of nature into the museum. The NHM’s light boxes showed this display. Some of the photographs included the people looking at the dioramas. Others seemed to emanate from within the dioramas. The NHM’s opening also included a two-month discussion series. Taking place inside the tent, the series included artists, writers, and activists organized into panels on institutional critique, the Anthropocene, museum patronage, urban planning, and climate justice.

The enormous tent gave the feeling of both an exhibition and an expedition. It resonated with Occupy, linking the occupation of the Queens Museum to the political movement and making the natural history museum legible as a political form for climate change struggle. There are natural history museums all over the world, a preexisting infrastructure ready to be activated against those who would use it to legitimate continued drilling, fracking, and coal, oil, and gas production. In the position of political collectivity, the tent ampliWes the affective engagement that accompanies the “diorama feeling” of nature’s power and vulnerability, otherness and awe. Under the same tent, visitors become part of the collective that is splitting the museum between the people and the corporation, oligarchy, or industry seeking to present knowledge in its interest. The NHM’s tent turns visitors into occupiers, implicating them in a counterpower infrastructure. It divides the space of its installation within itself, creating a new, divisive collectivity.

As I mentioned, the NHM is a dues-paying member of the American Alliance of Museums (AAM). Less than six months after the NHM’s launch, its director was invited to serve as a guest author of the blog of the AAM’s key initiatives.[14] At the MuseumExpo accompanying the AAM’s 2015 annual meeting, the NHM had the largest exhibition space. It brought its bus and enormous tent into the Georgia World Congress Center in Atlanta, where it highlighted fossil fuel industry greenwashing in science and natural history museums. Volunteers from the NHM distributed fliers to visitors with answers to questions commonly posed to museum professionals trying to navigate through the funding pressures of neoliberal capitalism and the ideology of “authoritative neutrality” in the context of climate change.

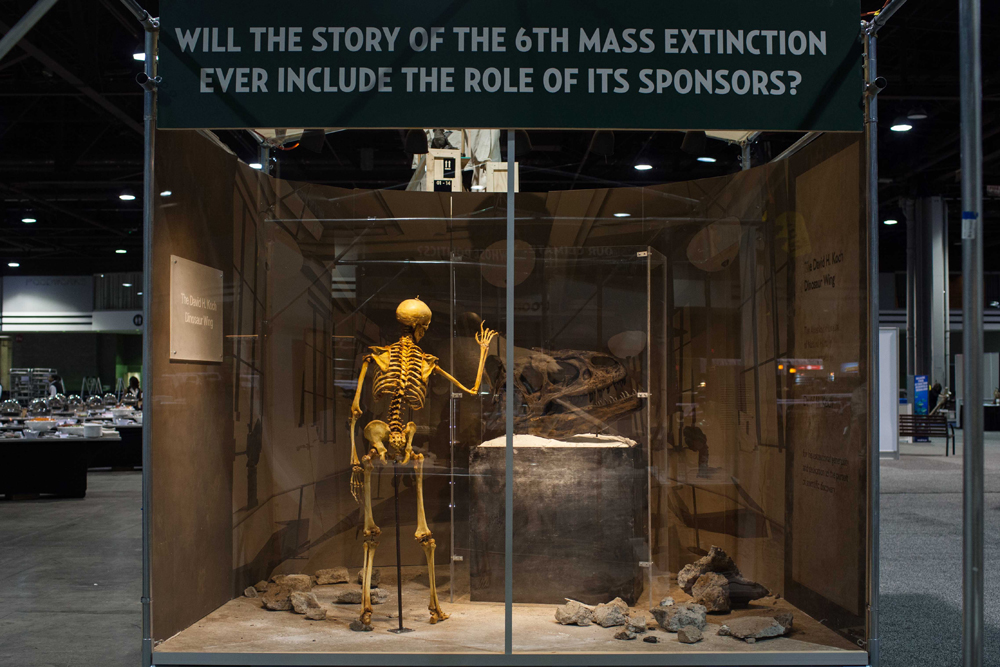

One large installation re-created the famous polar bear diorama from New York’s American Museum of Natural History’s 2009 climate change exhibition. The NHM’s version included previously excluded political–economic content regarding David Koch, who at the time served as a member of the board of the American Museum of Natural History. Where the original diorama featured a polar bear confronting the detritus of consumerism, the NHM’s diorama exposed what lies beneath the surface: a large oil pipe from Koch Industries. The NHM pushes to the surface the infrastructure that the American Museum of Natural History would prefer to keep submerged: the fossil fuel industry driving climate change that also supports the American Museum of Natural History.

A second installation gestured to Hans Haacke’s 2014 show at the Paula Cooper Gallery. Haacke not only exhibited a number of water pieces but also showed a new work attacking the Metropolitan Museum of Art for its new David H. Koch Plaza. This work displayed fake hundred dollar bills flowing down out of images of the new Koch fountain. The NHM installation continued the deployment of fountains, water, tubing, and Koch’s use of the cultural capital of museums to deflect critique from his consistent use of the political system to thwart environmental regulations. The installation featured a water system comprised of two tanks and a water fountain. One tank was identified as water from the American Museum of Natural History. Its accompanying description, modeled after a similar description used at the American Museum of Natural History, commends the cleanliness of New York City water. The second tank of water is identified as coming from North Pole, Alaska. This water is contaminated by sulfolane, a chemical from a Koch-owned refinery that leaked for years into the community’s groundwater, making it undrinkable. The NHM’s water system displays the pipes and tubes connecting the tanks and the fountain (itself a direct replica of one in the American Museum of Natural History).

In March 2015 the NHM released an open letter to museums of science and natural history signed by dozens of the world’s top scientists, including several Nobel laureates. The letter urged museums to cut all ties with the fossil fuel industry and with funders of climate obfuscation. After its release, hundreds of scientists added their names. News of the letter went viral, appearing on the front pages of the New York Times, Washington Post, and LA Times, and featured in the Guardian, Forbes, Salon, Huffington Post, and elsewhere. A leading climate change denial and obfuscation organization, the Center for the Study of Carbon Dioxide and Global Change, countered with a petition of its own.[15] One of the signatories is Willie Soon, a solar physicist who works at the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Soon attributes climate change to sunspots. He has received over a million dollars in funding from the fossil fuel sector, including the Charles G. Koch Charitable Foundation.[16]

Later in the summer, the NHM’s bus operated as a platform for speakers delivering a petition with over four hundred thousand signatories demanding that the Smithsonian Institute remove David Koch from their board. By the end of the summer, it was clear the NHM was having an impact: the California Academy of Sciences, one of the science institutions specifically targeted in a joint initiative of the NHM and 350.org, announced that it was phasing out investments in and relations with the fossil fuel sector. Just a few months later, Koch himself stepped down from his spot on the board of the American Museum of Natural History. Although a spokesperson from the museum said that the campaign against Koch “absolutely did not factor in his decision,” all of the coverage of his resignation noted that it was a symbolic victory for the activists.[17]

The Art of Political Engagement

Not An Alternative’s art of political engagement take shape as four interrelated elements of the NHM: collectivity, division, infrastructure, and truth. Each element is expressed along the three dimensions I mentioned at the outset: political organizing, artistic project, and theoretical laboratory.

Collectivity

The premise of the NHM as an organizing platform is that institutions matter as combined and intensified expressions of power. More than just the aggregation of individuals, they are individuals plus the force of their aggregation. Because institutions remain concentrations of authority that can be salvaged and put to use, it makes political sense to occupy rather than ignore or abandon them. We can repurpose trusted or taken-for- granted forms.

Natural history and science museums are interesting sites for political seizure and occupation. They retain public confidence as vehicles for science education. At the same time, they are threatened by budget cuts and market imperatives. So they are typically nonprofit, donor-and grant-dependent organizations, focused on cultural rather than commodity production. Yet they are forced to compete for visitors in the dense marketplace of entertainment. This subjects their staffs and boards to a particular pressure: how to retain their commitment to truth and the collective good in the face of opposing political and economic demands. The NHM makes this split within museums explicit. It uses it to organize museum workers, scientists, and visitors. Crucial to this endeavor have been the scientist sign-on letter and the petition calling for museums to break ties with the fossil fuel industry. Aggregated through the NHM, previously disconnected scientists present themselves as a collective force against climate denialism, obfuscation, evasion, and greenwashing. Even more, they are a collective force.

The NHM treats its visitors (understood broadly) as split between an understanding that something is wrong with the world and their own position within the world. After thirty years of neoliberalism’s intensification of individualism, visitors are likely to relate to the world as individuals and to think of the world’s problems as particular (crises, threats, events) rather than as systemic, interconnected. They are unlikely to see themselves as part of a collective that experiences these problems together and as differently—unevenly, unequally—together. Some museum professionals (whether consciously or not) reinforce individualist and individualizing expectations. They conceive exhibitions in terms of individual affective response. They model displays on the basis of individual use of screens and information acquisition. They attend to individual consumption opportunities (souvenirs). In contrast, the NHM presumes an unconscious desire for collectivity. Even if they don’t know it, visitors come to the museum looking for connection to a collective and a world from which they feel alienated: in a setting of deep cultural cynicism and mistrust, natural history museums remain among the most trusted institutions.

Expressed in psychoanalytic terms, the consumer orientation of funds-hungry contemporary museums depends on keeping visitors stuck in the circuits of drive, deriving enjoyment from the kicks of catastrophe. It focuses them on spectacles of climate change (extinction, extreme weather) and the ever-receding “great unknown” in nature. In contrast, the NHM incites their desire. Pointing at the capitalist system as the interior limit of what is considered nature, the NHM inscribes a gap in the great unknown. It presents the particular horrors of the world as connected (as systemic). Nature isn’t some kind of awesome exterior. It’s interior to human economic and political systems.

The NHM, then, operates in one respect as an activist organization, a pop-up museum and alternative institution with a mailing list, social media presence, and menu of cultural offerings. Yet it is also the generic museum that is present in every museum of natural history. It exists to force the already present split toward the common that every particular museum of natural history operating in a capitalist setting is forced to occlude.

the environmental group 350.org to call on top science and natural history museums to divest

Wnancial holdings from fossil fuel companies. Graphic by the NHM.

Division

The NHM mobilizes division as it organizes scientists and museum professionals against fossil fuel greenwashing. One of the challenges of this work is the hegemony of the claim that scientists and museums must be neutral, objective, “above” politics. The NHM confronts this claim by pointing out the claim’s own limit in the purpose of the museum. As asserted in the Code of Ethics for Museums, the museum is responsible for fostering “an informed appreciation of the rich and diverse world we have inherited” (qtd. in Lyons and Economopoulos). It is obligated to preserve this inheritance for posterity, providing a common resource for humankind. To this end, natural history museums must not generate legitimacy for those who would undermine the very possibility of a future. The NHM compels the institution to serve the people. Or, better, it enables the institution to function as one of the means through which the people serve themselves—taking care neither to promote the particular interests of billionaires and oligarchs nor to refrain from addressing issues of urgent collective concern.

As the NHM emphasizes in the flier it distributed to museum professionals at the MuseumExpo as well as in an editorial in the Guardian, neutrality is a myth. It hides from view the process determining the alternatives toward which it is ostensibly required to be neutral. This process is political. It benefits some and harms others. As Steve Lyons and Beka Economopoulos (2015) explain, “The claim to authoritative neutrality is dangerous, precisely because it prevents institutions from seriously re-evaluating their roles in a time of climate crisis. At a time when powerful lobbies representing the interests of the fossil fuel industry seek not only to influence public policy but also buy the next election, we can only see neutrality as another word for resignation.” In the face of conflict over the truth, the museum loses credibility when it fails to take the side of science. Even worse, it betrays the trust inseparable from its institutional form.

Some view nature in terms of the privilege of the few, the few who can own it, and the few who can access it. Others view nature in terms of all of us, as if we were not divided in our relation to nature, as if nature were not violent, ruptured, cataclysmic. The NHM takes its orientation to nature from two basic insights: nature is common and what is common is divided. We struggle over what is common. We fight to keep it common. The fact of this struggle alerts us to division, conflict, antagonism: nature has never been in balance. Nature doesn’t just exist. It insists beyond the limits of the known. What we can’t see and don’t know impresses itself on how and what we see. The NHM thus brings out the politics excluded from representations of nature as either originally in balance or external to human life. Any demarcation of a field is divisive, an inclusion and an exclusion. The NHM’s insistence on division, then, is not in the interest of some fantasy of full inclusion but rather for the purpose of mobilizing the exterior back within the institution. The excluded becomes inflected back in a torsion that repurposes, even reprograms, the institution.

Division goes all the way down. Science is itself divided, a never-ending struggle of methods, metaphors, egos, observations, paradigms, fields, and schools. It proceeds by affirming and rejecting, defending and defeating, knowledge that aspires to truth.

Infrastructure

The NHM seizes and repurposes the generic form of the museum as a set of institutionalized expectations, meanings, and practices that embody and transmit collective power. Cultural institutions tasked with science education become legible in their role in climate change, as sites of greenwashing and counterpower. In this latter sense, the NHM takes hold of the collective that is already present (as institutionality), redirecting it against that which exploits it.[18] Just as the museum is a site in the infrastructure of capitalist class power—with its donors and galas and named halls—so can it be a medium in the production of a counterpower infrastructure that challenges, shames, and dismantles the very class and sector that would use what is common for private benefit.

The aesthetics of the NHM, then, is more than relational. It’s political. The intent is not to create a transformational experience or new appreciation of community. It is to achieve concrete political goals: divestment from fossil fuels, organization of scientists into a divisive collective, appropriation of the museum form in climate change struggle, seizure of institutions of knowledge production and cultural transmission, and building a counterpower infrastructure. Here the NHM has more in common with the historic avant-garde than it does with the participatory art of the nineties. As Claire Bishop argues, the former positioned itself in relation to primarily Communist Party politics. The latter hyped itself in communicative capitalist terms that equated participation with democracy even as it lacked both a social and an artistic target (Bishop, 283–84). The NHM doesn’t promote awareness and debate. It pushes collective will formation. And it does so by giving a name and form to such a divisive will. As an avant-garde artistic project linked explicitly to an ongoing political movement, the NHM exposes an omission or failure on the contemporary Left: the lack of a revolutionary party or common name and form for the global struggle of the proletarianized.

Truth

The NHM states that its mission is “to affirm the truth of science. By looking at the presentation of natural history, the museum demonstrates principles fundamental to scientific inquiry, principles such as the commonality of knowledge and the unavoidability of the unknown.”[19] This mission is a generic statement of the fact that the credibility of museums of natural history comes from their fidelity to truth. Truth is partisan. It’s not a matter of consensus. Scientific truth forces itself beyond and through the practices and intentions of those who labor in its name. It is not identical with what scientists do and hence not reducible to its instrumentalization by capitalism and the state. In the theoretical language of Not An Alternative: science is not identical with itself. It is pushed and shaped by the real of a truth exterior to it.

T. J. Demos notes the dilemma that climate denialism poses for environmental activists. When we appeal to scientiWc expertise, we defer responsibility, giving up science to the dominance of states and capitals able to fund and deploy it; when we resist scientiWc expertise, we begin the slide into an inadvertent alliance with climate denialism, with the eco-thugs of extractive industry who spend billions to protect their interests by any means necessary. Demos argues, “Facing this dilemma, one must be aware of the fact that whatever we know about the environment—knowledge that will determine our future actions and chances of survival—we owe to the diverse practices that represent it” (18). The NHM locates itself at the site of these representational practices. Its wager is that insofar as science is shaped by a truth exterior to it, science cannot itself communicate its partisanship. Even as scientists are involved in practices through which they “fight to the death” or, in other words, in which they pursue and defend findings and methods as if their life depended on it, they tend to support a view of scientific practice as a whole as neutral and objective. Critics of corporate-funded science, industry-funded science, state-funded science, racist science, sexist science, and colonialist and imperialist science rightly and repeatedly demonstrate the falsity of this claim. All these particular enactments of scientific practice propel themselves by enclosing what is common within the limits enabling the practice. The practice of science is configured by its settings, settings to which it contributes. But the truth of science is not the same as the practice of science.

2015. Diorama in an exhibition at the American Alliance of Museums Annual Convention,

Atlanta, Ga., depicting the David H. Koch Dinosaur Wing at the American Museum of Natural

History in New York several hundred years into a dystopian future. Photograph by the NHM.

To affirm this truth is to force a gap within scientific practice, making science the truth of a subject. With a technique that might be described as overidentification or mimetic exacerbation, the NHM produces an elaborate staging not just of what natural history museums could be but of the form of the natural history museum promises. It promises a collective encounter with a world, a universe, a knowledge common even when distant and unknown. It holds out the force of a truth that impacts and shapes us in ways that are unknown and unpredictable not because they are outside of or distanced from human representations, institutions, systems, and struggles but because they are indelibly inscribed within them. Such a truth can only be accessed indirectly, anamorphically, through the screen of the museum as a form faithful to its communication. Because it is tethered to this truth, the NHM doesn’t invite cynicism. It doesn’t try to mobilize doubt. On the contrary, it hails viewers (and, indeed, the museum itself) as likewise faithful to the truth, as those who would be and are outraged when institutions that communicate scientific knowledge are compromised and corrupted. The NHM takes the subjects of truth and organizes them as the subjects of a politics.

Conclusion

If the Anthropocene is a concept that sutures fields (a useful formulation from Elizabeth Povinelli), then the anamorphic gaze is a perspective that inscribes division and finds politics in the gap. The NHM models such a split, demonstrating how institutions are forms of collectivity that matter and that can be seized. Their missions, styles, structures, and personnel, their very form, can be conscripted into a service they may not know that they support. The NHM confirms the existence of a truth that its visitors already know such that this truth becomes something more than an individual hunch—something with symbolic registration. Their perspective, like the system itself, is already collective. The challenge is for whom: for individuated visitors or for partisans in organized political struggle? The NHM arranges collectivity, division, infrastructure, and truth so as to cut through the anthropocenic enjoyment of helpless fascination with the spectacle. Rather than remaining satisfied with the critique of the institution for what it excludes, for what it cannot say, the NHM identifies with and amplifies the collective desire that already infuses it. As an activist platform, it does the work of political organization. It doesn’t get lost in cynicism, failure, melancholia, or the endless circuit of critique. It doesn’t aim to democratize or pluralize. It doesn’t aim to activate passive spectators but rather to organize active scientists and museum workers. The NHM enables them to take the side they are already on as it mobilizes natural history museums as politicized camps in a class war against the fossil fuel sector at the heart of the capitalist system. Targeting the institution it salvages a preexisting language and infrastructure, claiming it as a common resource. It thereby provides an experiment in seizing the state that can, and must, be replicated.

Works Cited

Badiou, Alain. 2009. Theory of the Subject. Trans. Bruno Bosteels. London: Continuum.

Bishop, Claire. 2012. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London: Verso.

Carter, Holland, and Robert Smith. 2015. “The Best Art in 2015.” New York Times, December 9.

Center for the Future of Museums (blog). 2015. “The Limits of Neutrality: A Message from The Natural History Museum.” April 23. http://futureofmuseums.blogspot.com/2015/04/the-limits-of-neutrality-message-from.html.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2009. “The Climate of History: Four Theses.” Critical Inquiry 35, no. 2: 197–222. CO2 Science. 2016. “‘To the Museums of Science and Natural History’—An Open Response.” April 16. http://www.co2science.org/articles/V18/apr/museumlet terresponse.php.

Connolly, William E. 2013. The Fragility of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Davis, Heather, and Etienne Turpin, eds. 2015. Art in the Anthropocene. London: Open Humanities Press.

Dean, Jodi. 2006. Zizek’s Politics. London: Routledge.

———. 2012. The Communist Horizon. London: Verso.

———. 2016a. “The Anamorphic Politics of Climate Change.” E-Flux 69 (January). http://www.e-flux.com/journal/the-anamorphic-politics-of-climate-change/.

———. 2016b. Crowds and Party. London: Verso.

Dean, Jodi, and Jason Jones. 2012. “Occupy Wall Street and the Politics of Representation.” Chto Delat 10, no. 34. https://chtodelat.org/b8-newspapers/12-38/jodi-dean-and-jason-jones-occupy-wall-street-and-the-politics-of-representation/.

Demos, T. J. 2009. “The Politics of Sustainability: Art and Ecology.” In Radical Nature: Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet, 1969–2009, Barbican Art Gallery, 17–28. London: Koenig Books.

Donovan, Thom. 2011. “5 Questions (for Contemporary Practice) with Not An Alternative.” Art21, May 19. http://blog.art21.org/2011/05/19/5-questions-for-contemporary-practice-with-not-an-alternative/#.VAxzBvldWSo.

Evans, Brad, and Julian Reid. 2014. Resilient Life. Cambridge: Polity.

Fraser, Andrea. 2011. “From the Critique of Institutions to the Institution of Critique.” In Institutional Critique. Ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, 408–17. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Geilung, Natasha. 2015. “Protesters Urge the Smithsonian Institution to Cut Ties with Climate Denier David Koch.” Think Progress, June 15.

Gills, Justin, and John Schwartz. 2015. “Deeper Ties to Corporate Cash for Doubtful Climate Researcher.” New York Times, February 21.

Kingsnorth, Paul. “Dark Mountain Project” (the self-published manifesto is available at http://dark-mountain.net/about/manifesto/).

Lacan, Jacques. 1998. Seminar XI: The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. Ed. Jacques-Alain Miller. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Norton.

Landsbaum, Claire. 2016. “Climate Denier David H. Koch Leaves American Museum of Natural History’s Board.” New York Magazine, January 21.

Lyons, Steve, and Beka Economopoulos. 2015. “Museums Must Take a Stand and Cut Ties to Fossil Fuels.” Guardian, May 7.

McKee, Yate. 2013. “DEBT: Occupy, Postcontemporary Art, and the Aesthetics of Debt Resistance.” South Atlantic Quarterly 112, no. 4 (Fall): 784–803.

———. 2014. “Art after Occupy—climate justice, BDS, and beyond.” Waging Nonviolence, July 30. http://wagingnonviolence.org/feature/art-after-occupy/.

McKibben, Bill. 2010. Eaarth. New York: Times Books.

Morton, Timothy. 2013. Hyperobjects. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Natural History Museum, The. 2016. “About the Natural History Museum.” https://thenaturalhistorymuseum.org/about/.

Not An Alternative. 2015. “The Radical Subject of the Post-Apocalyptic Generation.” In The Art of the Real: Visual Studies and New Materialisms. Ed. Roger Rothman and Ian Verstegen, 86–100. Newcastle-upon- Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

Parenti, Christian. 2011. Tropics of Chaos. New York: Nation Books.

Raunig, Gerald, and Gene Ray, eds. 2009. Art and Contemporary Critical Practice. London: MayFlyBooks.

Rosler, Martha. 2011. “Lookers, Buyers, Dealers, and Makers.” In Institutional Critique. Ed. Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson, 206–35. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Steyerl, Hito. 2009. “The Institution of Critique.” In Art and Contemporary Critical Practice. Ed. Gerald Raunig and Gene Ray, 13–19. London: MayFlyBooks.

Thompson, Nato. 2012. Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art From 1991–2011. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Wark, McKenzie. 2015. Molecular Red. London: Verso.

Jodi Dean is the Donald R. Harter ’39 Professor of Humanities and Social Sciences at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York. She is the author or editor of twelve books including, most recently, The Communist Horizon (2012) and Crowds and Party (2016). She is also a member of Not An Alternative.

“A View from the Side: The Natural History Museum” was originally published in Cultural Critique 94 (Fall 2016): 74-101.

- [1]An earlier version of some of the points developed here appears in “The Anamorphic Politics of Climate Change,” e-flux 69 (January 2016).↩

- [2]My description here positions enjoyment within the economies of desire and drive. For a fuller account, see Dean 2006.↩

- [3]A wide array of contemporary thinkers, activists, and artists are working with the themes of climate change, extinction, and the Anthropocene. My aim is not to criticize a particular person or work but to name a current present to greater or lesser degrees in the larger conversation or cultural milieu that has resulted from the uptake of the Anthropocene as the name for a problematic within the humanities. Examples could thus include Kingsnorth; McKibben; Morton; Evans and Reid; Chakrabarty; Connolly; Wark; the contributions to Davis and Turpin; and many others.↩

- [4]For an overview of the wide array of artistic practices brought together under the umbrella of socially engaged art, see Thompson.↩

- [5]For an elaboration, see Badiou; Dean 2016b.↩

- [6]Carter and Smith include Not An Alternative in their “The Best of Art in 2015.”↩

- [7]See also Bishop’s (2012) critique.↩

- [8]See Dean and Jones.↩

- [9]See also the periodization in Raunig’s and Ray’s (2009) preface.↩

- [10]See Raunig and Ray.↩

- [11]See Rosler.↩

- [12]See Not An Alternative (2015).↩

- [13]See Geilung.↩

- [14]See “The Limits of Neutrality: A message from The Natural History Museum,” Center for the Future of Museums (April 23, 2015). Available at http://futureofmuseums.blogspot.com/2015/04/the-limits-of-neutrality-message-from.html.↩

- [15]See “To the Museums of Science and Natural History—An Open Response,” (April 16, 2016). Available at http://www.co2science.org/articles/V18/apr/museumletterresponse.php.↩

- [16]See Gills and Schwartz.↩

- [17]See Landsbaum.↩

- [18]See Not An Alternative (2015).↩

- [19]As stated on its website: https://thenaturalhistorymuseum.org/about/.↩