With every superstorm, flood, drought, or heatwave, the uneven effects of climate change are made clear. Coastal communities in the poorer nations are displaced from their homelands while wealthy nations move to tighten border restrictions. Private fire services are hired to protect mansions from wildfires as working-class neighborhoods burn to the ground. The most exploited workers toil in dangerously hot and humid conditions as the managerial classes work from air conditioned offices, or, increasingly, from home. Climate change is not waging direct violence so much as it is heightening the contradictions of capitalism, clarifying the stakes of struggle.

Out of these contradictions, people around the world are turning to old and new ideas and tactics. In Ecuador and Bolivia, Indigenous and socialist activists and politicians have instituted the Rights of Nature as official policy, establishing new legal levers and precedents to ward off the predation of the fossil fuel industry in the Amazon rainforest. In the US, the Red Nation is organizing for Indigenous socialism, connecting the slow violence of climate change to the ongoing and systemic violence of capitalism and settler colonialism. Proposals for Red, Black, and Internationalist Green New Deals are being churned out and vigorously debated.

As IPCC reports set their sights on the not-too-distant future, a wide range of researchers and activists have been turning, perhaps counterintuitively, to the past. Nikole Hannah-Jones’s 1619 Project (2019) presents a reframing of US history, placing the long history of slavery at the center of the country’s national narrative. David Graeber and David Wengrow’s bestselling The Dawn of Everything (2021) turns to the origins of humanity to unearth the diverse forms of social organization that preceded the rise of capitalism, with the audacious aim of figuring out “how we got stuck.” In the environmental humanities and social sciences, academics are fighting over the presumed origins of the contemporary climate, environmental, and extinction crises, questioning the appropriate name and time scale of our geological epoch. At the same time, people are tearing down colonial and Confederate monuments, integrating histories of injustice and rebellion into school curricula, calling for offensively named places to be renamed, and fighting for the repatriation of cultural artifacts stolen by imperialists centuries ago.

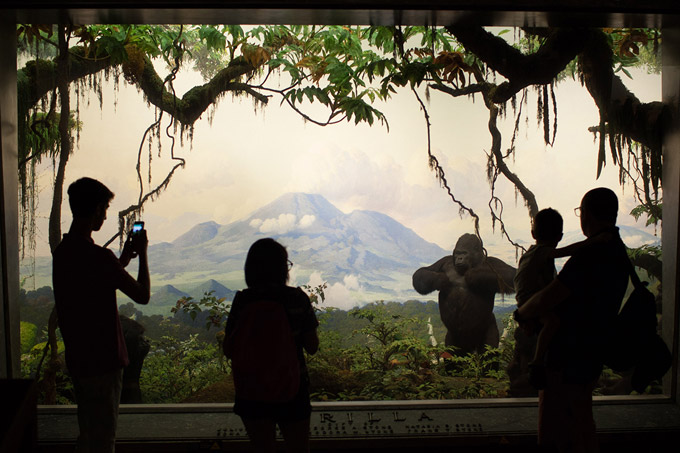

Natural history’s institutions have become key symbolic targets in this widespread reckoning, not least because they put colonial violence on full display. Not only do many natural history museums still contain offensive and racist dioramas and displays constructed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but, as currently constituted, their legitimacy owes everything to the past and ongoing dispossession of Indigenous Peoples, both their material cultures and, across the Americas, their stolen lands. On the one hand, natural history museums can be considered monuments to colonialism, landmarks that function to naturalize capitalist and colonial relations to the world. On the other hand, recent counter-tours at major museums in London and New York City show that museums can also serve as training grounds for seeing from an anti-colonial, anti-capitalist perspective.

As daily news headlines remind us that the future of planetary life is in peril, it may be tempting to see the contemporary struggles over historical markers, events, monuments, and museums as distractions from the main event. It is clear that some camps seek refuge in the past, finding comfort in a projected return to an original state of nature, while others are looking to atone for some original sin. However, there are others, still, who are not looking for salvation, but for alternate traditions, lessons, tools, and epistemologies that might be reworked and mobilized in our struggles for a just and livable world.

This edition of Periscope emerges from this latter tendency, making a case for how history, and natural history in particular, can help orient contemporary struggles for life beyond extraction. To this end, contributors have been asked to engage with a new critical concept, red natural history, which names a tradition of natural history that is not built on colonial or capitalist relations, but on a comradely and reciprocal relation to land, life, and labor. As a perspective and a praxis, red natural history seeks to hold together an insurgency of scientists, scholars, and communities, whose individual and collective practices seek to leverage natural history’s disciplines, methods, tools, and institutional resources in support of contemporary struggles for climate and environmental justice.

What is Red Natural History?

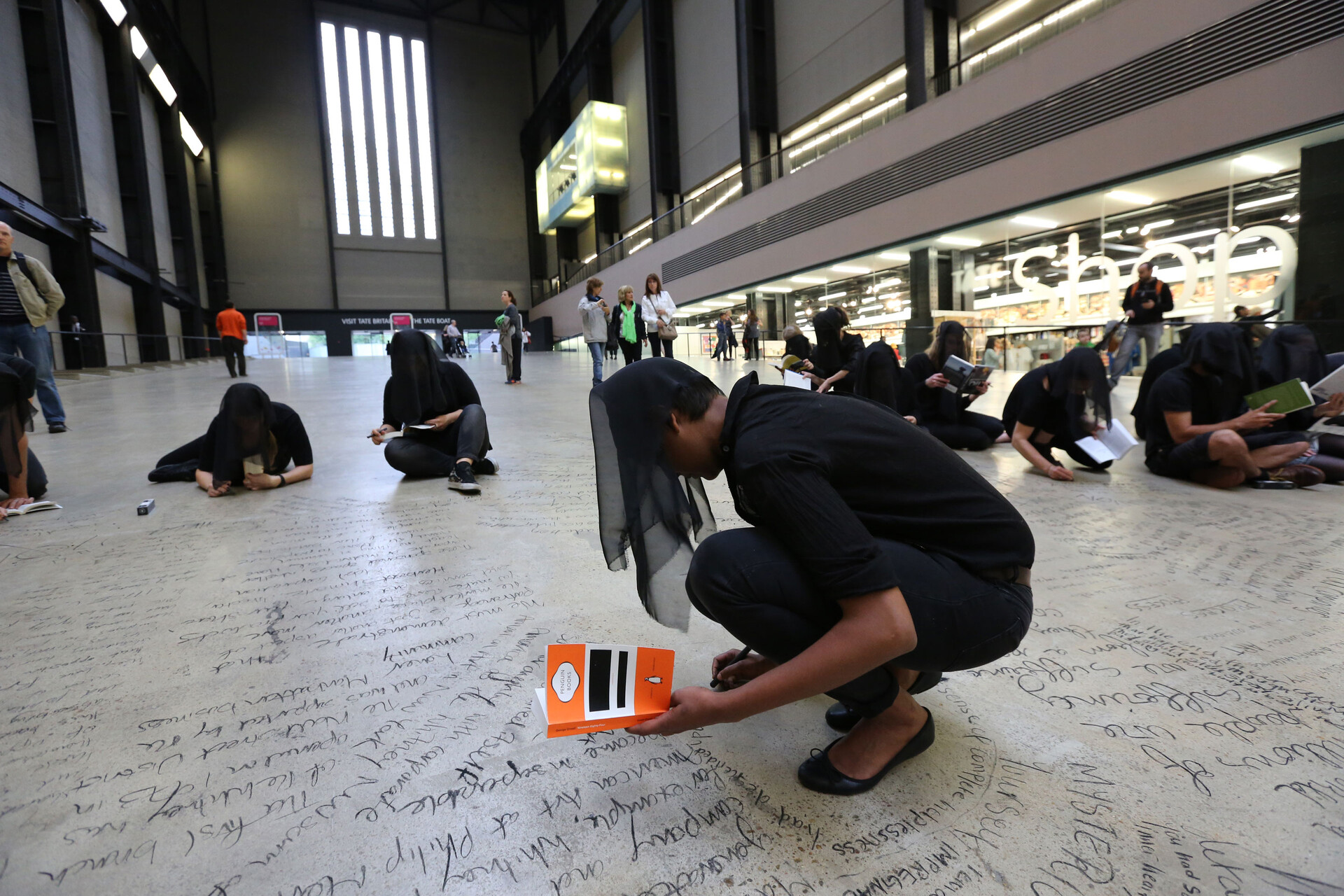

This edition of Periscope was edited by Not An Alternative, a collective of artists, activists, and theorists that has spent most of the past decade developing The Natural History Museum (2014-), a traveling museum that leverages the power of history, museums, monuments, and movements to change narratives, build alliances, educate the public, and drive civic engagement in support of community-led movements for climate and environmental justice. This ongoing project started from the hypothesis that science and natural history museums are not monolithic totalities fully determined by their imperialist foundations or the capitalist interests that they have historically served. Instead, they are collective infrastructures riven with internal divisions. Our initial goal was to organize an insurgency within the US sector for science and natural history museums—to take the sector as a site of struggle, with the aim of seizing some of its institutional resources to support ongoing movements and campaigns.

From the beginning, it was clear to us that there were radicals working in natural history’s disciplines and institutions—scientists, scholars, and educators—who did not want to passively trace the slow degradation of the planet, but to actively get in the way, whether by working directly with communities to expose the impact of industrial pollution on public health, protecting sacred objects or human remains in the path of proposed pipelines, or sounding the alarm about the systemic causes of climate change. We went to conferences with anthropologists, archaeologists, geographers, natural scientists, conservationists, and museum curators, where we were introduced to the range of engaged research practices, radical working groups, and advocacy initiatives that scholars and scientists have developed to support community-led and place-based environmental struggles. While often marginalized within their disciplinary associations, and encouraged to compete among themselves for scarce resources, such initiatives represent an emergent tendency within natural history, which Not An Alternative believes can be organized into a powerful infrastructure for community-led movements.

After working for several years to organize alongside scientists, archaeologists, and museum workers, it has become clear to Not An Alternative and many of our comrades that to represent a position of difference, the many dispersed and largely atomized insurgents within natural history’s disciplines and institutions would do well to both name and organize around an alternate tradition of natural history. This dossier is part of our effort to propose a name for this other tradition, and to work out some of the theoretical foundations and practical applications that might give it substance and meaning.

Our proposal is that red natural history can serve as the name for the array of practices and perspectives that fall under the purview of natural history but break from its dominant imperialist tradition.

Why Red?

The “red” of red natural history names the Other to natural history as it is conventionally understood, the part of natural history that neither capitalism nor colonialism can capture or put to use. As part of the language in commonthat ties together communist, socialist, and Indigenous traditions of resistance, “red” does not signify a stable identity, but a common alienation from the capitalist world.

In the Indigenous tradition, the term “red” was historically understood as a derogatory slur, meant to racialize Indigenous Peoples and differentiate them from white settlers in North America. With the Red Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s, the color was reclaimed as an affirmative signifier of Indigenous cultural identity. From the American Indian Movement’s use of the red logo on its flag, to the Indigenous climate justice movement’s reference to Mother Earth’s “red line,” to the red handprints and red dresses that powerfully assert the unjustly ignored epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, to recent political programs like the Red Deal, red has had a central place in the language in common of Indigenous movements within and beyond North America for more than a half-century.

In the socialist tradition, the color red has also been a key means of differentiating comrades from enemies. From the common deployment of the red wedge, red star, and red sunset in international communist art and propaganda to the use of red bandanas by striking workers in the early US labor movement, “red” has been a central part of the language through which the international workers of the world have communicated their struggles for liberation.

The relationship between Indigenous and socialist or communist reds is not simply analogical. Not only did Marx and Engels take inspiration from Iroquois modes of life and forms of social organization, but socialist ideology has been crucial for many decolonial movements across the world, from the liberation struggles of the African Party for the Independence of Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde (1963-1974), to those of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in Chiapas, Mexico (1994- ). These entanglements speak to the ways in which people have worked together to engage, renew, and weave together multiple ways of knowing and traditions of thought and action in their collective emancipatory struggles. They also remind us that there are real reasons why during the so-called “red scares” of the past two centuries, Indigenous Peoples, communists, anarchists, and the dispossessed and exploited peoples of the world have been lumped together, treated as part of one coordinated conspiracy to overthrow capitalism.

In positing the existence of “Red Natural History,” our hope is to inspire others to draw from the many traditions of anti-colonial and anti-capitalist thought and action to advance a natural history worthy of the name.

About This Dossier

This edition of Periscope was inspired by the hypothesis that natural history is not completely determined by its colonial or imperialist traditions. Rather, natural history as it has come to be known is the enclosure and instrumentalization of a much broader project with diverse (and not exclusively European) origins. For our part, Not An Alternative broadly defines natural history as the project of seeing, relating to, and coming to understand the material world. There are ways of relating to the world as a wealth of natural resources, and ways of relating to the world as a world in common that cannot be enclosed. Red natural history names the project of seeing, relating to, and understanding the world as a world in common. Our collective introduced this concept in “Towards a Theory of Red Natural History,” published in Society & Space last May, outlining red natural history as a speculative project—a framework to elaborate a tradition from which the world beyond the capitalist world can be made to appear.

If natural history is a mode of seeing, presenting, and tracing the forces that have produced the world we live in, it is by definition partial and partisan. One objective of red natural history is to train ourselves to see from the perspective of the part that the dominant tradition of natural history has systematically barred from view. Red natural history is attuned to the forces, both human and other-than-human, that heighten the contradictions through which change becomes possible, the forms of more-than-human comradeship that sustain the threat to the capitalist world system. It reveals the untold people’s histories of insurrections, mutinies, strikes, and rebellions as plots co-produced with the land, water, and animal, outlining how people work with their environments in their struggles for justice and liberation just as they have historically leveraged the most exploitative labor conditions to produce the oppositional power they need. The stories that might be chronicled by red natural history attend to storms, fires, rebellions, and egalitarian lifeways in equal measure—to all signs of abundance that betray the enclosures violently imposed upon the world in common.

This dossier brings together Indigenous historians, geographers, and knowledge keepers with non-Indigenous scholars, theorists, and artists to engage with red natural history, not as a fully formed concept, but as a field of inquiry. It should be stressed, however, that this field of inquiry is not open-ended. It is grounded in a shared commitment to the struggle for collective liberation. The essays follow their own paths, but point toward four central theses:

1. Natural history is split. Just as there is an imperialist tradition of natural history, there is another, non-colonial tradition of natural history, which can be made visible through practices of interpretation. Describing the case of a Kaapoisaamiiksi (a headdress traditionally worn by Amskapi Piikani women) in the Field Museum’s collection, Rosalyn LaPier demonstrates how objects of natural history are never completely enclosed, even as they are bought, sold, and subject to display in the world’s most powerful natural history museums. For LaPier, the material cultures of Indigenous Nations are neither conduits to a precolonial ideal, nor are they simple artifacts of dispossession. They tell a complex history of both dispossession and resilience, revealing violent economies of extraction, but also a system of relations that is illegible to the settler-colonial gaze—an Indigenous world, where things are done differently. Andrew Curley turns to the history of the Dilophosaurus wetherilli, a dinosaur skeleton found by a Diné man on the Navajo Nation in 1940, only to be confiscated by paleontologists from the University of California, Berkeley two years later. Curley compels us to see the imperialist tradition of natural history as a grounded practice built on expropriation and Indigenous erasure, but he also offers, through his interpretation of the Dilophosaurus, a blueprint for another kind of natural history: one that situates its objects within the long history of struggle against colonial dispossession.

2. Red natural history insists on the power of history writing in the practice of history making, precisely by developing narrative arcs that orient contemporary struggles for social and environmental justice. It does not seek to understand the world as it exists (appealing to some illusory neutrality), but to take the past as a source for building consciousness and collective political will. In this sense, red natural history participates in what Ruth Wilson Gilmore (following Raymond Williams) describes as the “selection and re-selection of ancestors,” from which traditions of resistance are made and remade. In his contribution to this dossier, Ashley Dawson turns to the anarchist tradition to identify, in both human and other-than-human systems, a primordial commonality that runs against the logic of predation governing the capitalist world. He draws on Peter Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid to elaborate a dissenting tradition of biology, which, in emphasizing the role of cooperation in species evolution, opposed the dominant nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century understanding of evolution as a “struggle of each against all.”

3. Red natural history has the capacity to orient movements within and against the university. As a practice of seeing, interpreting, and relating to the world, red natural history extends a broad net over a range of academic disciplines, suggesting the need for both self-criticism and transformation in the sciences, social sciences, and the practical fields of landscape architecture, planning, and design. Kai Bosworth explores the tradition of radical geography, which emerged in the 1960s as an answer to geography’s imperialist legacy, asking what radical geography can do to not only redress geography’s past wrongdoings, but also actively contribute to contemporary struggles for environmental justice. Natchee Blu Barnd elaborates how ethnic studies might be conceived as a branch of red natural history, showing how, as the study of difference and differentiation conducted from the perspective of the oppressed, ethnic studies embodies the antithesis of the imperial tradition of natural history. Billy Fleming turns to landscape architecture and the design professions, asking how designers and landscape architects can forge alliances with insurgent movements for climate and environmental justice. He surveys the work of the Designing a Green New Deal studio, which he runs at the University of Pennsylvania, giving a sense of how design education might be shaped around the imperatives of red natural history, most directly by training students to produce tools that can be put to use in regional struggles.

4. Red natural history is not simply a critical project. It is a constructive, affirmative one, which seeks to find, in the gaps of the capitalist world, the signposts of another world, and from this other world, another natural history. Alberto Acosta argues that the Andean concept of buen vivir offers a vision of another world that is incommensurate with the capitalist world, proposing a combination of tactics and struggles that might bring about the “pluriverse,” which is a term that Indigenous activists and communists in Latin America are organizing around to signal a break from the Western tradition of global development. Dina Gilio-Whitaker writes from a hundred years in the future, and like Acosta, she insists that mass extinction is not guaranteed. Starting from the hypothesis that there is no future without decolonization, she works backwards to imagine the shifts that must take place to turn against the tides of climate catastrophe. Gilio-Whitaker joins with others in the Periscope dossier to insist on the power of revisiting the past from the perspective of a future where justice prevails.

The contributions to this edition of Periscope come together in their resolute commitment not to historicism—to seeing things “as they really were”—but to the constructive project of seeing in (natural) history the opening from which another world has always existed—a world in common that is built and sustained through reciprocal relations between people, animals, and the land. This is not a conclusive statement on what red natural history is and does. More than anything else, it is an invitation to others to join in the struggle to determine the pathways through which the red in natural history can come into view.

–Steve Lyons for Not an Alternative

Not An Alternative (est. 2004) is a collective that works at the intersection of art, activism, and theory. The collective’s latest, ongoing project is The Natural History Museum (2014–), a traveling museum that highlights the socio-political forces that shape nature. The Natural History Museum collaborates with Indigenous communities, environmental justice organizations, scientists, and museum workers to create new narratives about our shared history and future, with the goal of educating the public, influencing public opinion, and inspiring collective action.