In their search to define the root cause of the climate crisis, many on the environmentalist left are zeroing in on a peculiar target: not the economic division between haves and have-nots, nor the geopolitical division between the nation and the world, but the conceptual division between society and nature—as though dissolving this conceptual division provides a kind of miracle cure to the ecological ills of fossil capitalism.[1] For this camp, the most urgent political task of our era is to heal the divide between humans and nonhumans, to make kin with nonhuman others, to imagine and create a kind of multispecies unity that, as the logic goes, should bring about a more harmonious, and thus more sustainable system of relations between people, animals, and the land.

This common sense has underwritten curatorial initiatives across the fields of contemporary art and architecture, from the Venice Biennale’s 2021 architecture exhibition How will we live together? to the Curatorial Design workshop on “Designing for Cohabitation” at the Canadian Center for Architecture, where I presented the first draft of this text. The workshop proposed to investigate “the issue of architectural design for humans and non-humans,” with a focus on the Montréal Insectarium, a brand-new institution co-designed by Wilfried Kuehn, a core member of the Curatorial Design team. The Insectarium is an architectural experiment in “biophilic design,” based on the hypothesis that humans have a primitive desire to connect with other living organisms, which can be reawakened with the assistance of immersive design.[2] Underlying this principle of “biophilia” is the idea that by rekindling affections between humans and nonhumans, a new ethical paradigm will come into being, and from this new ethical paradigm, a more liveable future for all. From this vantage, museums and science centers are understood as apparatuses that can not only help visitors break free from their dualist habits of thought, but also promote a multispecies consciousness from which a radically new environmental politics can begin to take root. The question is whether this new environmental politics is the politics we need.

For Not An Alternative, the answer is no. To put it very briefly, we argue that this project of “healing the divide” does not rearrange human-nonhuman relations, but more accurately, reframes them. In the process, it also frames out, or obscures, the fundamental antagonisms that structure relations between and among humans, animals, and lands. When we start with the question of how to design for cohabitation, or how to mend the gap between humans and nonhumans, we take a shortcut. Instead of grappling with the material and economic structures that are dealing death to so many for the benefit of a few, we incorporate them, naturalize them, or otherwise take them for granted.

We can see the effects of this framework at Montréal’s science museum complex Space for Life, which, in addition to the Insectarium, includes the Montréal Biodome, the Montréal Botanical Gardens, and the Rio Tinto Alcan Planetarium. The complex hosts a whole range of microclimates and ecosystems designed to inspire visitors to “rethink and cultivate a new way of living.”[3] But this “rethinking” takes place within a complex that is sponsored by Rio Tinto, the world’s second largest mining corporation. Space for Life’s constructed lifeworlds survive off the surplus capital produced out of Rio Tinto’s world-destroying practices, while Rio Tinto, in desperate need for what Mel Evans calls a “social license to operate,” survives off the positive public relations provided by eco-conscious institutions like Space for Life.[4] With the unrestricted call to “cohabit,” we’re invited to figure out how to live together in plural harmony, without figuring out what we cannot live with.

What is the principle of unity implicit in this frame—a frame that invites us to heal the divide between humans and nonhumans without naming, let alone doing away with, the forces that are set up to extract life and deal death in the short and long term? What if our first question is not “how do we design for cohabitation,” but “who are we, and what, if we are to live together, needs to be done?” What would it mean to build a Space for Life premised on the elimination of Rio Tinto and its world?[5] To pursue this line of thought, I will outline three different principles of unity that have structured museum practice, and our interpretation of it, at various times and in various places, and which have reinforced specific relations between humans and nonhumans, civilization and its Other. We can provisionally name these principles fascist unity, liberal unity, and communist unity.

Fascist Unity

We can begin with fascist unity. Fascist unity is the unity of the nation or “master race,” conceived as one bounded collective against all others. The unifying horizon of fascism is premised on the eradication of everything beyond its self-imposed and rigorously guarded borders. As Nazi Germany made crystal clear, fascism’s dream of unity is realized by means of extermination and eugenics. It’s no wonder that the large natural history museums of London, Paris, and New York, among others, were major supporters of the eugenics movement of the early 20th century.[6]

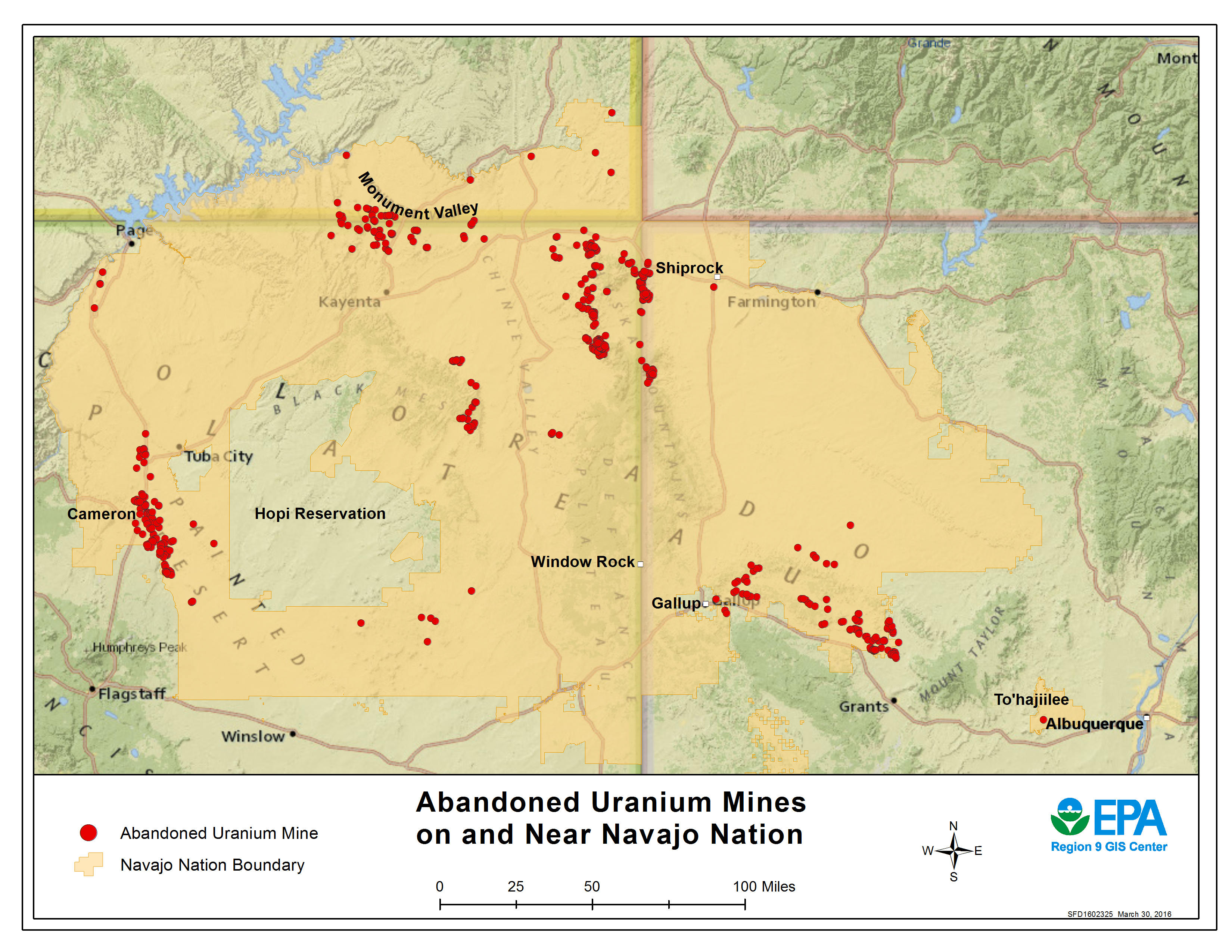

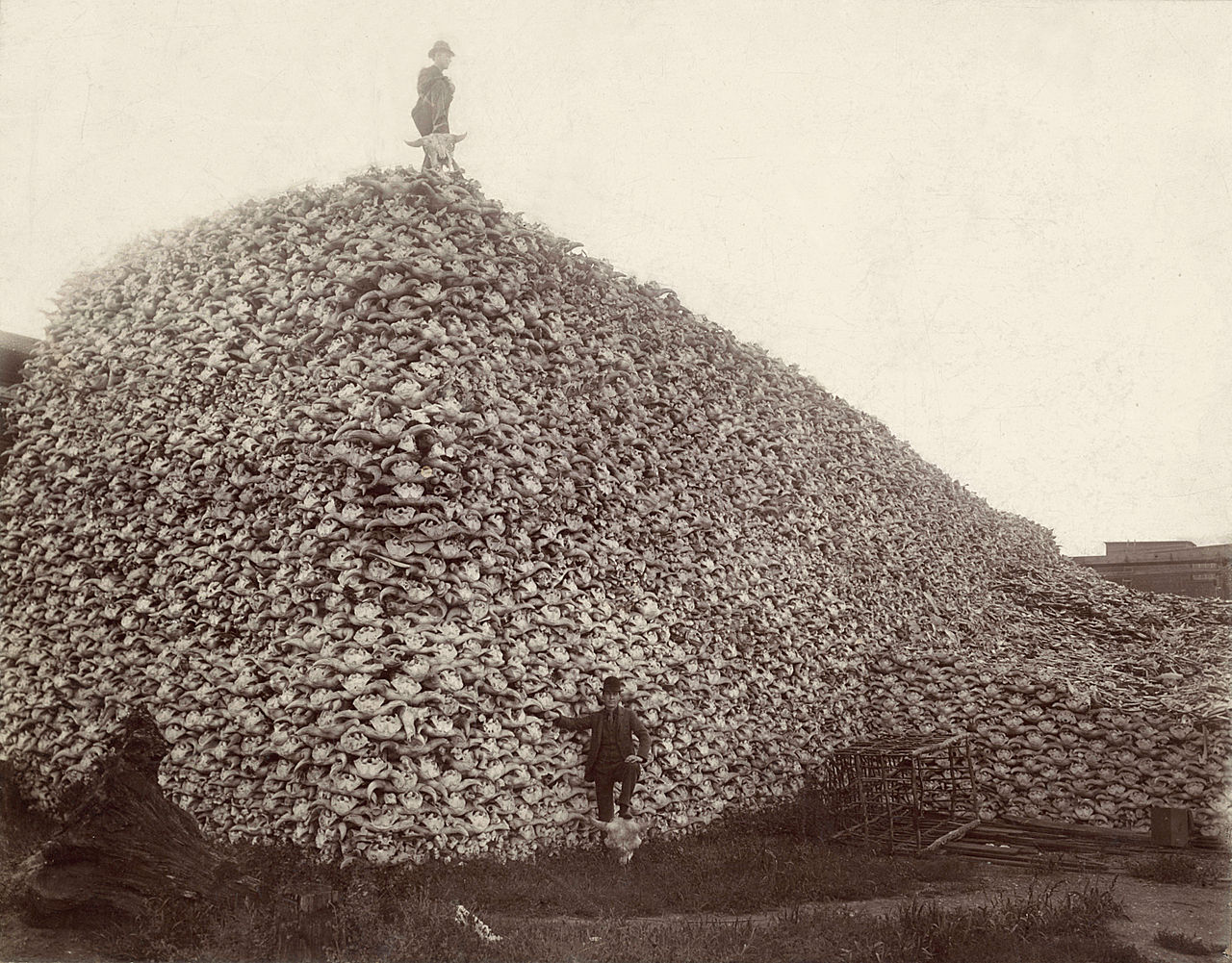

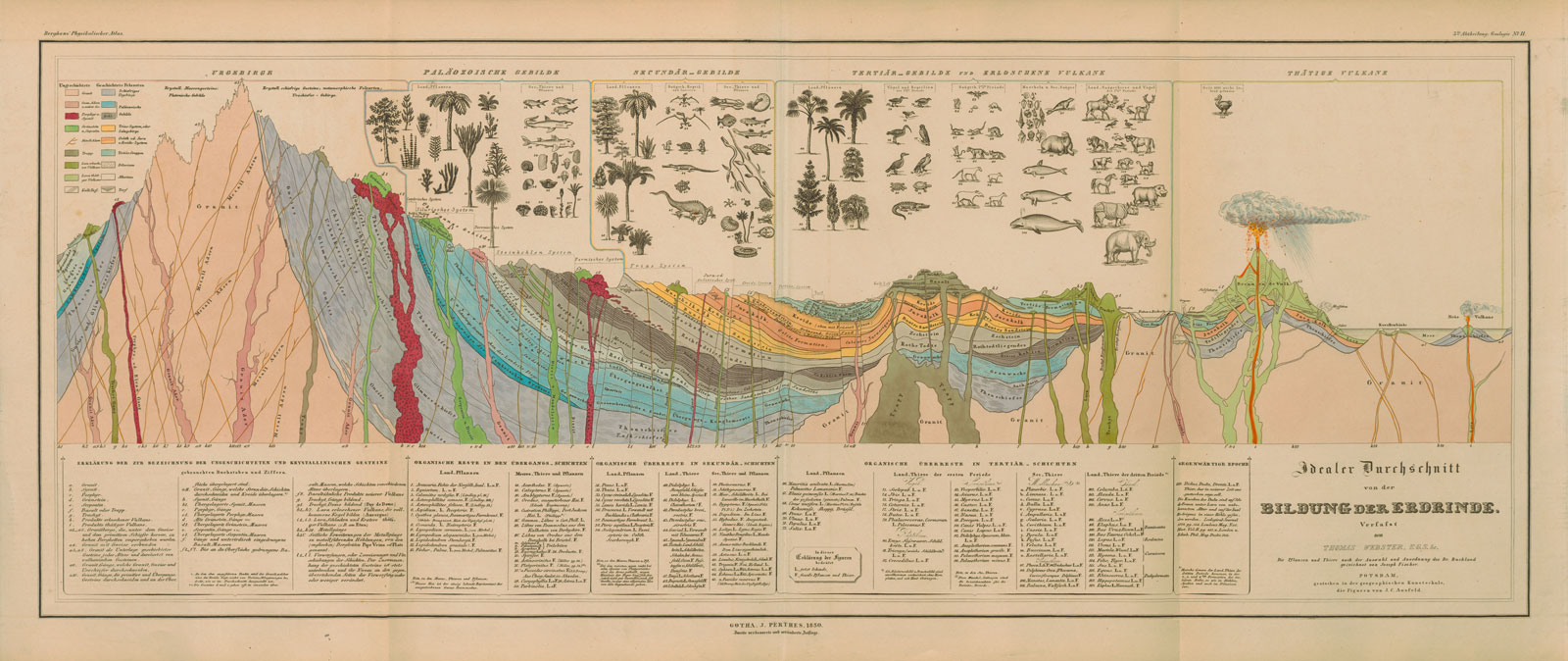

As outgrowths of the imperialist campaigns of the 19th and 20th centuries, such museums were put to use in the building of fascist unity. They served this function by collecting and displaying as “natural history” everything that was deemed to be outside the domain of civilization. We can see how this underlying logic naturalized weird combinations—making human zoos, prehistoric megafauna, rocks, exotic animals, insects, and Indigenous cultures appear at home under a single roof. By putting human and nonhuman others on display, the large natural history museums of the major imperial powers helped to produce the unity of their nations, training their visitors to develop a distinct racial consciousness—a sense of collectivity based on the difference between viewer and viewed. This sense of collectivity cut across classes, working for capitalism precisely by obscuring antagonisms between workers and bosses who were of the same nation and/or race. Museums of this kind trained citizens to distinguish themselves from nonhuman others, cultivating the fetishization, hatred, and subordination of the nonhuman—including oppressed groups (from slaves to dispossessed Indigenous Nations) whose asserted inhumanity was a precondition for capital accumulation in the colonies.

Liberal Unity

If fascist unity is the unity of one nation against the rest, liberal unity is the unity of the whole world holding hands, where there are no divisions, where “all lives matter.” By integrating all things within a conceptual unity, liberalism obfuscates essential differences and undermines the basis for political struggle. Liberal unity is liberal because it rests on a notion of equality founded on universal inclusion—all positions can be harmonized and managed within the social whole. It is the project of mending divisions between “us” (inferred as white and middle-class people) and historical Others (from Black people to animals and mushrooms) by assimilating, including, or recognizing them within an already-existing social structure that presupposes that all relations are relations between self-possessed individuals. In this assimilative process, collective modes of relating to life and land are outlawed or pushed underground.[7] Where fascism fights class struggle by fostering a patriotism that cuts across class lines, liberal unity undermines the basis for class struggle by denying the fundamental antagonisms that distinguish us from them.[8]

Where fascist unity is most clearly invoked and produced by the great natural history museums of the 19th and early 20th centuries—the museums that continue to be subject to the most sustained protest and anticolonial critique—liberal unity finds form in the Montréal Insectarium’s “biophilic design,” which itself builds upon a tradition of ecological design developed during the mid-to-late 20th century. Consider the famous Penguin Pool at the London Zoo, designed by Berthold Lubetkin and the Tecton Group in 1934. As Peder Anker among others have shown, the Penguin Pool stood as a revolutionary innovation in environmental design because it broke from the longstanding “naturalistic” method of zoo design—the attempt to “reproduce the natural habitat” of the animal—in favor of what he calls a ‘geometric’ method, which attempts to present animals in unnatural settings, more closely resembling the built environment.[9] As Anker argues, this method of design was an effort to model a principle of “healthy coexistence,” which presupposed that “[a]ll species could prosper if they were given the opportunity to live in a healthy and peaceful environment.”[10]Again, the injunction to “co-exist” shifts our attention away from the structures and forces that threaten existence, leading to the kinds of ideological distortions that enable us to imagine an ethical way of designing animal cages for human entertainment.

If the Penguin Pool offers a model of hybridizing human and nonhuman environments, gesturing toward a unity that transcends the assumed difference between humans and nonhuman others (we can all thrive in reinforced concrete environments!), the Paris Museum of Mankind, renovated in 2015, underscores how liberal unity is established through the incorporation and assimilation of sites, species, and cultures that point to a world beyond the capitalist world. Here, visitors are confronted with a massive collection of cultural objects from around the world, where Nike sneakers are positioned next to Indigenous moccasins, peacefully coexisting within the same display cases. Radically upending the drama of the traditional natural history museum, where the fundamental antagonism between civilization and its Others is cast in the harsh light of day, this antagonism is swallowed up at the Museum of Mankind, incorporated but left unresolved.

Here, capitalist culture is subjected to the same ethnographic gaze as the “primitive cultures” whose objects were collected and preserved as spoils of imperial conquest, training us to see a sameness that transcends the fundamental differences that made so-called primitive non-capitalist societies Other to modern capitalist civilization in the first place. We leave the museum less equipped to understand why some cultures, ways of life, and economic systems have been targeted for extinction, less equipped to recognize the noncapitalist world these cultures represent, and less equipped to see the threat they pose to the capitalist state.

Communist Unity

So, what of the third principle of unity, what I’m calling communist unity? To start, I should clarify that what I want to develop is not a definition of the unity produced by the Communist Internationals of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but a principle of unity that precedes communism’s organized form, which late nineteenth-century elites like Gustav Le Bon and Andrew Carnegie derided as “primitive communism.”[11] Primitive communism does not name the organized form of communism, but the abject other to capitalist civilization. As a name, it holds together the communists, anarchists, agitators, Indigenous peoples, heretics, witches, and their nonhuman comrades, all those who have, throughout history, threatened and exceeded the perspective of the capitalist state, which places at its center the white, male, propertied individual. Unlike both fascist unity and liberal unity, communist unity is not premised on the annihilation of the Other, but on a fidelity to it. It is a project of building the outside as a world apart—a world in common that capitalism cannot accommodate or enclose. Communist unity, thus, can be defined as the open, unbounded unity of a collective that comes together in the struggle to make a world according to principles of non-exploitation and non-domination. The “we” it calls into being is not fully formed. It is spectral, existing in the nightmares of the capitalists, and it is embodied, at different times and places, in the world-building practices of the oppressed.

It may be clear by now what the museum of natural history that is aligned with this principle of unity ought to do. In short, it ought to train us to take the perspective of the Other. This natural history museum does not presuppose civilized visitors who define themselves against the objects it contains. Rather, it invites its visitors to take the side of the Other, a side occupied by every being—human and other-than-human—whose subordination has been necessary for the making of the capitalist world. The museum of natural history that is built on communist unity does seek to heal the divide between humans and nonhumans or between “us” and “them.” Instead, it fosters the consciousness of the Other that fascism is determined to destroy. Communist unity is, in other words, fascist unity’s combative antithesis.

Producing a unity of the oppressed and excluded—this is the historical project of communism, and, as Geo Maher makes clear in his recent book Anticolonial Eruptions, it is the project of revolutionary decolonization as well.[12] Massimiliano Tomba theorizes the “insurgent universality” that has guided the emancipatory struggles of proletarians, slaves, women, and Indigenous peoples, who asserted themselves as “the excess of the term ‘man’ with respect to the law and to every essentialist definition of the human.”[13] This insurgent universality does not necessarily exclude nonhuman beings. As Oxana Timofeeva argues in “Communism with a Nonhuman Face,” communist unity necessarily extends beyond the realm of the “human” into the animal realm. Quoting from a poem by Russian poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, she underscores the relation between humans and nonhumans that her expansive idea of communism invokes: “You send sailors / To the sinking cruiser / there / where a forgotten kitten was mewing.”[14] As Timofeeva explains:

There is something absurd and irrational in the excessive generosity of the revolutionary gesture depicted by Mayakovsky – imagine how crazy an army commander would have to be to send a battalion of sailors, adult armed men, to risk their lives for the sake of some forgotten, tiny, politically insignificant creature. And yet, that’s precisely how the drama of revolutionary desire should be performed.[15]

This drama is not set into motion by the communist’s empathy for the plight of the kitten, but a full identification with it. It is not a struggle for dignity, inclusion, or recognition, but a struggle of and for the undignified and unrecognized. The communist and the kitten are on the same side.

The natural history museum that is aligned with this project supports the development of a unity between comrades, whether they are living or dead, human or nonhuman. It asserts that those who enter it are entering the domain of the other and invites them to cross over to the other world.

The Museum of the Other World

Since 2014, Not An Alternative has been running The Natural History Museum (NHM)—an experiment in modeling this kind of museum—a museum that contributes to the production of collectivity between and among oppressed groups in their common struggle against fossil capitalism and the extractive industries. A “museum for the movement,” NHM works with scientists, museum workers, Indigenous water protectors and land defenders, and community-led environmental justice organizations to build infrastructure for environmental struggle. After spending our first few years campaigning to get fossil fuel oligarchs and climate deniers like David H. Koch removed from the boards of some of the country’s largest natural history museums, we have spent the past seven years developing campaigns, exhibitions, and public programs with communities that have been cast as civilization’s Other, including Indigenous Nations struggling to protect sacred places from fossil fuel extraction and transport, as well as other communities on the frontlines of environmental injustice, whose lives are treated as disposable by corporations and the state.[16]

Much of our recent work has been developed in close collaboration with the House of Tears Carvers, a group of carvers and community leaders from the Lummi Nation, an Indigenous Nation in the Pacific Northwest. For more than a decade, the House of Tears Carvers has been carving totem poles, putting them on flatbed trailers, and bringing them to communities across North America to build alliances in the struggle to protect the land and water. The “totem pole journeys” visit Indigenous communities, farmers and ranchers, scientists, and faith-based communities, engaging groups in ceremonies led by Lummi elders. Connecting communities on the frontlines of environmental struggle, these journeys seek to build, through ceremony, a collective that did not previously exist. Our most recent collaboration with the House of Tears Carvers, the Red Road to DC (2021), was a cross-country totem pole journey that aimed to support local communities’ efforts to protect sacred places threatened by dams, mining, and oil and gas extraction. Stopping for ceremony at ten key sacred sites, including Bears Ears National Monument and Standing Rock, before arriving at the national capital in Washington DC for a cross-community gathering, the project was designed to both symbolize and strengthen bonds of solidarity between communities whose local campaigns to protect sacred places combined into one collective force. The Red Road also elaborated our vision for a museum that does not seek to protect the most treasured cultural objects from external threats, but to mobilize them as threats to extractive capitalism.

For our latest project, We Refuse to Die (2023), we are working with fence-line environmental justice communities across the US to advance a visual language that represents and holds together a coalition of the dispossessed and excluded as a powerful threat to capital.[17] From coastal Texas to Louisiana, rural Appalachia and where I grew up near Sarnia, Ontario, communities living in close proximity to refineries, pipelines, fracking sites, and other polluting infrastructure are forced to breathe toxic concoctions of benzene, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, formaldehyde, and other harmful pollutants, which even at low levels, produce deadly impacts for those who ingest them.[18] In Port Arthur and Freeport, Texas, St. James Parish, Louisiana, and Clairton, Pennsylvania, among other places, communities living near petrochemical refineries, fracking pads, and coal processing plants are experiencing horrifying rates of cancers, leukemia, birth defects, reproductive disorders, asthma, and heart disease, among other diseases. Forced to live in unlivable conditions, they are cast as the living dead—written off as “externalities” on an economic ledger. Responding to this situation, we are working with communities in Appalachia, the Gulf South, and the Pacific Northwest, to reclaim the “living dead”—and the numerous popular incarnations of this figure—as protagonists and partners in our shared struggle for a world beyond extraction.

At the center of this initiative is a series of sculptures we call Externalities, representing various figures of the living dead—both humans and other animals. Hand-carved from trees killed in Pacific Northwest wildfires near where some of Not An Alternative’s members live (and where recent wildfire smoke caused the worst air quality in the world), the Externalities are being planted in the yards of Appalachia and Gulf South residents during community rituals, facing the petrochemical and fossil fuel infrastructures that contaminate local water supplies and pollute the air. As components within a multi-year, multi-city initiative, which includes the staging of public events, “toxic tours,” and community gatherings, these carvings bring together people from dispersed sites and struggles to perform a common ritual dedicated to metabolizing grief into collective strength and community power.

This project marks the beginning of the latest phase of our work, which is focused on seeding a visual language that can communicate, from a position of collective power, a relation between all those who have been cast as surplus—humans and nonhumans, living and dead. It does not seek to awaken fellow feeling between humans and nonhumans, but to awaken the desire for a communist world that the capitalist class has spent centuries pushing underground. It thus advances the project beneath the NHM: to model a museum that does not heal the divide but take a side, the side of the oppressed, excluded, and unhuman, who refuse to die but who refuse to live in the capitalist world.

Notes

[1] Donna Haraway, for example, argues that dissolving boundaries between human and nonhuman, nature and society, “cracks the matrices of domination.” See Haraway, Manifestly (University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 53. For a longer critique of this “dissolutionist” tendency in ecological thought, see Andreas Malm’s chapter “On the Use of Opposites,” in The Progress of This Storm (Verso, 2016), 177-196.

[2] Biophilia and biophilic design were outlined as core design criteria in the Space for Life’s call for architectural proposals, which prompted Keuhn Malvezzi’s winning proposal. See: “Montréal Space For Life Architecture Competition” (Bureau du design Montréal, 2014): 16-17: https://designmontreal.com/sites/designmontreal.com/files/ftp-uploads/planches/espvie/PDF/Programme_et_annexes_EN.pdf

[3] Karine Jalbert, quoted in “Space for Life: New way to view nature,” National Post (online, May 7, 2012): https://nationalpost.com/uncategorized/space-for-life-new-way-to-view-nature.

[4] Mel Evans, Artwash: Big Oil and the Arts (Pluto Press, 2015), 70. Understanding this reciprocity, it’s easier to understand why in 2020, Space for Life did not join in publicly denouncing Rio Tinto’s role in destroying a 46,000-year old Aboriginal sacred site in Western Australia that “provided a 4,000-year-old genetic link to present-day traditional owners.” See Calla Wahlquist, “Rio Tinto blasts 46,000-year-old Aboriginal site to expand iron ore mine,” The Guardian (online, May 26, 2020): https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/may/26/rio-tinto-blasts-46000-year-old-aboriginal-site-to-expand-iron-ore-mine.

[5] This turn of phrase is indebted to Jay Jordan and Isabelle Fremeux, who describe the historic struggle against “the airport and its world” at the ZAD in Notre-Dames-des-Landes, where a regional airport was slated for development. See Jordan and Fremeux, We Are ‘Nature’ Defending Itself: Entangling Art, Activism, and Autonomous Zones (Pluto Press, 2021), 56.

[6] Rob DeSalle, “The Eugenics Movement in Retrospect,” Natural History (Online, December 2021-January 2022): https://www.naturalhistorymag.com/features/093896/the-eugenics-movement-in-retrospect.

[7] See Steve Lyons and Jason Jones for Not An Alternative, “Towards a Theory of Red Natural History,” Society & Space (May 11, 2022): https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/towards-a-theory-of-red-natural-history.

[8] Alberto Toscano theorizes this “logic of pacification” in “Powers of Pacification: State and Empire in Gabriel Tarde,” Economy and Society, vol. 36, no. 4 (November 2007): p. 601.

[9] Peder Anker, From Bauhaus to Ecohouse: A History of Ecological Design (Louisiana State University Press, 2010), 19.

[10] Ibid., 22.

[11] From Gustav Le Bon to Andrew Carnegie, conservative elites at the end of the nineteenth century routinely described the desire for commonality simmering under the fabric of capitalist society as “primitive communism.” See Carnegie, The Gospel of Wealth, (The Century Co., 1900), 6. See also Gustave Le Bon, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, second edition (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1897), xvi.

[12] Geo Maher, Anticolonial Eruptions (University of California Press, 2022).

[13] Massimiliano Tomba, Insurgent Universality: An Alternative Legacy of Modernity (Oxford University Press, 2019), 14-15.

[14] Vladimir Mayakovsky, “Ode to Revolution,” quoted in Oxana Timofeeva, “Communism with a Nonhuman Face,” e-flux journal #48 (October 2013): https://www.e-flux.com/journal/48/60030/communism-with-a-nonhuman-face/.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Laura Pulido emphasizes the role of the state in reinforcing environmental racism in “Geographies of race and ethnicity II: Environmental racism, racial capitalism and state-sanctioned violence,” Progress in Human Geography (2016): 1-10.

[17] For more on this project, visit werefusetodie.org.

[18] Dayna Nadine Scott, “Confronting Chronic Pollution: A Socio-Legal Analysis of Risk and Precaution,” Osgoode Hall Law Journal vol. 46, no. 2 (Summer 2008): 293-343.

Steve Lyons is a core member of Not An Alternative, an art collective with a mission to affect popular understandings of events, symbols, institutions, and history. The collective’s ongoing project The Natural History Museum (2014-) began as a performative intervention in the museum sector. It has evolved into an infrastructure for place-based environmental justice struggles, with a focus on building and strengthening solidarity across geographies and between generations past, present, and future.

“From Healing the Divide to Taking a Side” was originally published in Curatorial Design. A Place Between, edited by Wilfried Kuehn and Dubravka Sekulić (Milan: Lenz Press, 2025).

Rosalyn LaPier (Blackfeet/Métis) is an award winning writer, ethnobotanist, environmental activist and Professor of History at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She/they work within Indigenous communities to revitalize Indigenous & traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), to address environmental justice & the climate crisis, and to strengthen public policy for Indigenous languages. The author of Invisible Reality: Storytellers, Storytakers and the Supernatural World of the Blackfeet (2017), she/they are a 2023-2025 Red Natural History Fellow. Rosalyn is an enrolled member of the Blackfeet Tribe of Montana and Métis.

Rosalyn LaPier (Blackfeet/Métis) is an award winning writer, ethnobotanist, environmental activist and Professor of History at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She/they work within Indigenous communities to revitalize Indigenous & traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), to address environmental justice & the climate crisis, and to strengthen public policy for Indigenous languages. The author of Invisible Reality: Storytellers, Storytakers and the Supernatural World of the Blackfeet (2017), she/they are a 2023-2025 Red Natural History Fellow. Rosalyn is an enrolled member of the Blackfeet Tribe of Montana and Métis.

Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes) is a Lecturer of American Indian Studies at California State University San Marcos and an independent educator in American Indian environmental policy and other issues. At CSUSM she teaches courses on environmentalism and American Indians, traditional ecological knowledge, religion and philosophy, Native women’s activism, American Indians and sports, and decolonization. She also works within the field of critical sports studies, examining the intersections of Indigeneity and the sport of surfing. Dina is the author of two books, most recently the award-winning As Long As Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice from Colonization to Standing Rock.

Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes) is a Lecturer of American Indian Studies at California State University San Marcos and an independent educator in American Indian environmental policy and other issues. At CSUSM she teaches courses on environmentalism and American Indians, traditional ecological knowledge, religion and philosophy, Native women’s activism, American Indians and sports, and decolonization. She also works within the field of critical sports studies, examining the intersections of Indigeneity and the sport of surfing. Dina is the author of two books, most recently the award-winning As Long As Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice from Colonization to Standing Rock. Ashley Dawson is professor of postcolonial studies in the English department at the Graduate Center, City University of New York and the College of Staten Island. His latest books include Environmentalism from Below: How Global People’s Movements Are Leading the Fight for Our Planet (Haymarket, 2024), Decolonize Conservation: Global Voices for Indigenous Self-Determination, Land, and a World in Common (Common Notions, 2023), People’s Power: Reclaiming the Energy Commons (O/R, 2020), Extreme Cities: The Peril and Promise of Urban Life in the Age of Climate Change (Verso, 2017), and Extinction: A Radical History (O/R, 2016). A member of the Social Text Collective and the founder of the Public Power Observatory, he is a long-time climate justice activist.

Ashley Dawson is professor of postcolonial studies in the English department at the Graduate Center, City University of New York and the College of Staten Island. His latest books include Environmentalism from Below: How Global People’s Movements Are Leading the Fight for Our Planet (Haymarket, 2024), Decolonize Conservation: Global Voices for Indigenous Self-Determination, Land, and a World in Common (Common Notions, 2023), People’s Power: Reclaiming the Energy Commons (O/R, 2020), Extreme Cities: The Peril and Promise of Urban Life in the Age of Climate Change (Verso, 2017), and Extinction: A Radical History (O/R, 2016). A member of the Social Text Collective and the founder of the Public Power Observatory, he is a long-time climate justice activist.

Kai Bosworth

Kai Bosworth