In his essay “Of Cannibals” (1580), Michel de Montaigne wrote of the recently discovered inhabitants of the so-called New World, “the laws of nature govern them still […] it is a nation wherein there is no manner of traffic, no knowledge of letters, no science of numbers, no name of magistrate or political superiority; no use of service, riches, or poverty, no contracts, no successions, no dividends, no properties, no employments, but those of leisure; the very words that signify lying, treachery, dissimulation, avarice, envy, detraction, pardon, never heard of.” Montaigne’s celebration of the egalitarian character of Indigenous culture bears striking similarity to many subsequent accounts of European encounters with Indigenous people, from Gonzalo’s famous utopian speech near the outset of Shakespeare’s The Tempest (1611) all the way to Françoise de Graffigny’s bestselling epistolary novel Letters from a Peruvian Woman (1747).

The idea of what came to be known as the “noble savage” was, in other words, wildly and enduringly popular in Europe. For many critics, this discourse was foundational to European racism. Yet in a talk given a year before his death, the anthropologist David Graeber remarks that scholars today tend to assume that Europeans of the time were so utterly racist that anytime they wrote of Indigenous culture they were essentially fabricating a series of stereotypes. In other words, these tropes may have allowed writers to satirize European society without being put in prison but were nonetheless based on completely imaginary versions of Indigenous culture. But what, Graeber asks, if the “dialogue with a savage” genre that developed in the years after Montaigne’s essay was instead a fairly accurate reflection of withering Indigenous critique of European social hierarchy and inequality?

How might texts such as those of Montaigne and Graffigny reflect a genuine unsettling of European assumptions about the “advanced” character of their grossly unjust societies, a disturbance resulting from encounters with Indigenous people? Furthermore, might we not see the ideas of racial hierarchy that were a mainstay of the disciplines of natural history that developed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as a defensive reaction to these critiques from the peoples Europe was trying to subjugate? What points of friction, what dissenting bodies of thought within the tradition of natural history testify to these challenges to scientific racism during the age of empire?

In this essay, I discuss Russian anarchist and scientist Peter Kropotkin’s under-acknowledged but groundbreaking book Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution (1902), arguing that the text reflects a politically radical stream of thinking within the discipline of biology. Kropotkin’s investigation of the forms of mutual aid within different animal species and, perhaps even more importantly, among different human cultures in the not-too-distant past retains its radicalism in a moment when solidarity and egalitarianism are pressing political exigencies. Kropotkin’s work resonates in significant ways with the tradition of thinking that derives from Montaigne and, if we follow Graeber’s argument, from the Indigenous critique of European social inequality. The mixture of scientific observation, speculations on evolution, and cultural critique evident in Mutual Aid might therefore be situated within a tradition that can best be termed red natural history.

How were European doctrines of racial supremacy generated and sustained in the face of the scathing Indigenous critiques of inequality evident in the work of Montaigne and subsequent writers such as Graffigny? During the eighteenth century, when these texts enjoyed such popularity in the context of critiques of European society, the natural history museum developed as one of the key sites for the manufacture of European doctrines of racial supremacy. As , natural history museums functioned from their inception during the Enlightenment as repositories for the objects and specimens collected on European colonial expeditions around the globe. They thereby provided public legitimation of European colonialism. The natural history museum developed alongside and functioned as a display space for taxonomy, the scientific discipline that named and classified biological organisms based on their shared characteristics. Das and Lowe report that in the eighteenth century, Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, who is generally considered the father of modern taxonomy, divided humanity along racial lines, describing Europeans as “governed by laws” while representing Africans as “governed by caprice.” Following this reasoning, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach’s On the Natural Varieties of Mankind (1776) helped to inaugurate the discipline of physical anthropology by classifying humanity into five fundamental types based on the geographical distribution of peoples.

By the nineteenth century, such typologies were linked to craniology, which established the purported superiority of white Europeans over other peoples through measurements of the shape of their skulls. Natural history museums displayed—and still display—these relics prominently, and scientists and other “collectors” competed to amass remains of Native American and other subjugated peoples. Assertations about anatomical difference between “races” of humans were linked to assumptions about civilizational inferiority and superiority after the advent of Darwin’s theory of evolution. For example, Thomas Henry Huxley, who was known as “Darwin’s bulldog,” wrote in his article “The Struggle for Existence in Human Society” (1888) that the animal world is akin to a gladiatorial contest, in which “the strongest, swiftest, and cunningest live to fight another day.” A similar situation, Huxley argued, obtained in human societies: “so among primitive men, the weakest and stupidest went to the wall, while the toughest and shrewdest […] survived.” Drawing on Darwin’s theory of natural selection, Huxley assumed that all life on Earth was characterized by a Hobbesian war of all against all and that the history of civilization was about the taming of these underlying violent drives.

Huxley’s views squared with those of Social Darwinists during the age of empire, who saw the European nation-state as proof of white male superiority and as a legitimation of the right to rule over other purportedly less advanced peoples, including the colonized peoples of the world, as well as the European working class and women. But there was a central, unacknowledged contradiction in these social-Darwinist arguments. For if life was at bottom a struggle in which the strongest and most cunning survived, what exempted the European ruling classes from this logic? Were they not simply the violent and wily victors of this struggle for survival? And, if so, weren’t European civilizational pretensions nothing but a veneer covering over and legitimating cruel rapacity? This is the import of Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz, the supposed emissary of European light, whose genocidal behavior and dying words (“The Horror! The Horror!”) reveal the lie of European claims to civilizational superiority in Heart of Darkness.

Yet the social Darwinism consecrated at powerful institutions such as natural history museums was not universally accepted. Indeed, there was an important but still underacknowledged scientific tradition that explicitly challenged this dominant strain of European natural history. Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution is the most powerful articulation of this dissenting, radical perspective. Born into the Russian aristocracy, Kropotkin chose to do his military service as a youth in the remote eastern provinces of the Russian empire, where he became involved in geographic survey expeditions in Siberia and Manchuria. There, he wrote subsequently in Mutual Aid, he observed two dominant factors in the natural world: first, the extreme severity of climatic conditions, which meant that animals, far from struggling with one another, struggled simply to survive; and, second, that animals of the same species did not fight one another but rather, in Kropotkin’s words, engaged in “Mutual Aid and Mutual Support carried on to an extent which made me suspect in it a feature of the greatest importance for the maintenance of life.” Drawing on these observations, Kropotkin wrote Mutual Aid as a direct challenge to the work of Huxley and other social Darwinists.

Despite his opposition to Huxley, Kropotkin did believe that species competed with one another. Indeed, he was explicitly critical of writers such as Rousseau, who saw in nature only love, peace, and harmony. Kropotkin agreed with Darwin’s arguments about competition among species as one of the motors for evolution. Importantly, though, Kropotkin suggested that mutual aid was the dominant feature of life within particular species, and thus within the animal world in general:

As soon as we study animals—not in laboratories and museums only, but in the forest and the prairie, in the steppe and the mountains—we at once perceive that though there is an immense amount of warfare and extermination going on amidst various species, and especially amidst various classes of animals, there is, at the same time, as much, or perhaps even more, of mutual support, mutual aid, and mutual defense amidst animals belonging to the same species or, at least, to the same society. Sociability is as much a law of nature as mutual struggle.

In making these arguments about mutual aid as a fundamental law of nature, Kropotkin drew on and developed the work of Russian naturalists such as zoologist K. F. Kessler, whose 1879 lecture on mutual aid in the animal world was an inspiration for Kropotkin’s subsequent book. As historian of science Daniel Todes argues, mutual aid was a broadly accepted core of the Russian intellectual tradition during the nineteenth century, which welcomed Darwin’s ideas about natural selection while also seeing the Malthusian assumptions about social stratification as a law of nature that undergirded Darwin’s early work on evolution as a product of a particular bourgeois English school of thought.

Far from being universally valid, this Malthusian influence on Darwin conveniently helped legitimate the class, race, and gender hierarchies of the Victorian age. In Mutual Aid, Kropotkin argues that Darwin in fact came to reject this facile position in later work such as The Descent of Man (1871), where, according to Kropotkin, Darwin pointed out how, “in numberless animal societies […] struggle is replaced by co-operation, and how that substitution results in the development of intellectual and moral faculties which secure to the species the best conditions for survival.” A great part of Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid consists of detailed studies of the complex forms of social solidarity found among species such as ants, parrots, and chimpanzees, sociability that he argues is responsible for these species’ superior self-organization and evolutionary success.

As Iain McKay explains in his excellent introduction to Kropotkin’s work, the insights about the animal world advanced in Mutual Aid have been abundantly corroborated by biologists in recent decades. Leading contemporary primatologist Frans de Waal for example writes that Kropotkin “rightly noted that many animals survive not through struggle but through mutual aid,” a position that he documents in detail in his book Good Natured. Noted paleontologist and evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould concurred, arguing that “Kropotkin’s basic argument is correct. Struggle does occur in many modes, and some lead to co-operation among members of a species as the best pathway to advantage for individuals.” As Iain McKay has documented, many other scientists have joined this chorus, including biologist Lee Alan Dugatkin, whose Cooperation Among Animals extends Kropotkin’s catalogue of animal mutualism exhaustively. Perhaps most surprisingly, this list also includes biologist Richard Dawkins, whose book The Selfish Gene shows that what he calls “mutualistic cooperation” is in fact often central to the successful transmission of an organism’s genetic heritage. George Monbiot’s account of the myriad form of cooperation that unfold among the organisms living in the ground under our feet in his recent book Regenesis is only the latest take on the complex, self-organizing systems that structure the natural world.

Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid was not only the first work to prove that cooperation was central to the survival of animals—it also extended this insight to human societies. Challenging the writing of previous utopian philosophers of the European Enlightenment, Kropotkin argued that human solidarity was based in the practices of mutual aid that had helped our species survive and evolve for thousands of years:

It is not love and not even sympathy upon which Society is based in mankind. It is the conscience—be it only at the stage of an instinct—of human solidarity. It is the unconscious recognition of the force that is borrowed by each man from the practice of mutual aid; of the close dependency of every one’s happiness upon the happiness of all; and of the sense of justice, or equity, which brings the individual to consider the rights of every other individual as equal to his own.

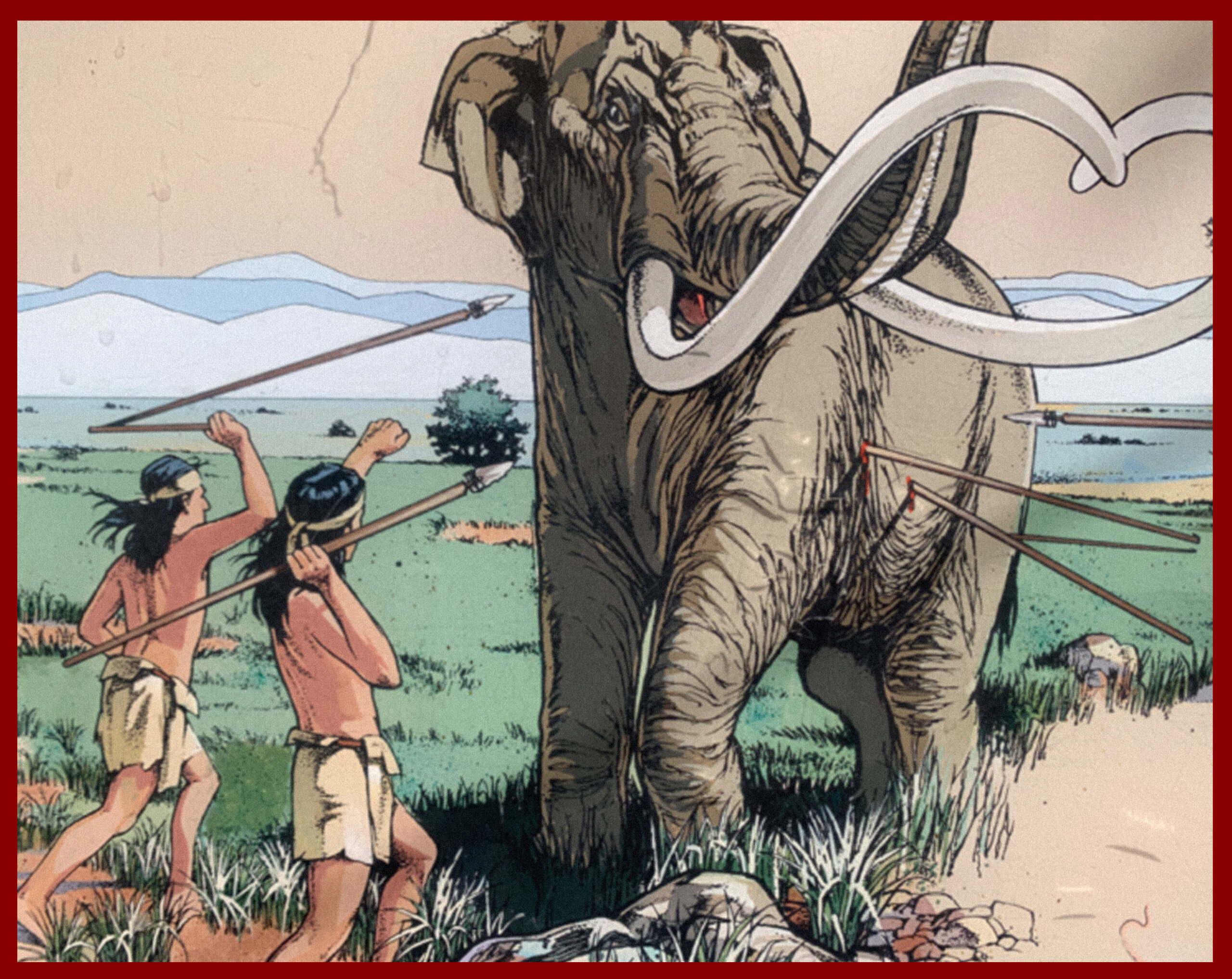

The second half of Mutual Aid consists of an exposition of this claim that the cooperative instinct is the basis of human society and solidarity. Drawing on recent anthropological research, Kropotkin argues that “the earliest traces of man, dating from the glacial or the early post-glacial period, afford unmistakable proofs of man having lived even then in societies.” This evidence directly contradicts the assumptions of Hobbes and successors of his like Huxley, who falsely represented, in Kropotkin’s words, “primitive mankind as a disorderly agglomeration of individuals, who only obey their individual passions, and take advantage of their personal force and cunningness against all other representatives of the species.” For Kropotkin, “societies, bands, or tribes—not families—were thus the primitive form of organization of mankind and its earliest ancestors.” The upshot of these insights about the prehistory of humanity is a damning indictment of contemporary European society and the competitive ethos that undergirded capitalism: “Unbridled individualism is a modern growth, but it is not characteristic of primitive mankind.”

When Kropotkin writes “primitive” in the preceding quotations, he refers to Homo sapiens during the earliest period of our existence as a species. But it was hard for even as radical a scientist and activist as Kropotkin to wholly escape the dominant evolutionary discourse of his day. Indeed, the chapters of Mutual Aid that deal with human cooperation are organized into analysis of “mutual aid among savages,” “mutual aid among the barbarians,” “mutual aid in the medieval city,” and “mutual aid among ourselves,” in an evolutionary schema that seems to replicate the kind of racist thinking on display in so many museums of natural history.

Yet Kropotkin inverts the evolutionary typology that these distinctions seem to encode by arguing that the forms of human solidarity evinced in the social organization of “savages” and “barbarians” have been eroded by the subsequent establishment of the state. Thus, for Kropotkin, the rise of the centralized state in the absolute monarchies of early modern Europe generated the conditions of selfish individualism necessary for the growth of capitalism. He argues that there were two main reasons for this: first, “in proportion as the obligations towards the State grew in numbers the citizens were evidently relieved from their obligations towards each other.” Equally if not more importantly, however, Kropotkin argues that states “systematically weeded out all institutions in which the mutual-aid tendency had formerly found its expression.” The success of this campaign of ideological and physical annihilation can be measured by the near-universal acceptance of the doctrine in biology that “the struggle of each against all is the leading principle of nature.”

But the battle of elites to destroy popular traditions of mutual aid and solidarity was not completely victorious. Kropotkin argues that “the nucleus of mutual-support institutions, habits, and customs remains alive with the millions; it keeps them together; and they prefer to cling to their customs, beliefs, and traditions rather than to accept the teachings of a war of each against all, which are offered to them under the title of science, but are no science at all.” As in the portion of Mutual Aid focused on the world of animals, Kropotkin elaborates myriad examples of institutions of cooperation and solidarity established by the multitude. Among these were the communal forms of agriculture practiced in peasant villages.

Kropotkin’s take here was likely shaped by the founder of the Women’s Union during the Paris Commune, a young Russian woman named Elizabeth Dmitrieff. Influenced by Nicolay Chernyshevsky’s novel What is to Be Done? (1863), Dmitrieff believed that collectivist rural organizations such as the Russian obshina could be nodes of the radical society to come. Other historical moments Kropotkin discusses include autonomous cities of medieval Europe, contemporary labor unions, and the “countless societies, clubs, and alliances, for the enjoyment of life, for study and research, for education, and so on, which have lately grown up.” Beyond the inherent interest of the historical examples he adduces from various epochs, however, the overarching point in Kropotkin’s account is that the elites who wield state power cannot succeed in stamping out the human instinct to engage in mutual aid. As Kropotkin puts it, “the mutual-aid tendency in man has so remote an origin, and is so deeply interwoven with all the past evolution of the human race, that it has been maintained by mankind up to the present time, notwithstanding all vicissitudes of history.”

Herein lies the significance of Montaigne’s account of Indigenous cultures with “no name of magistrate or political superiority.” Like the many other stinging Indigenous critiques of European society that David Graeber excavates in his lecture on the origin of theories of social inequality, Montaigne conveys the sense of life in a society in which mutual aid and cooperation had not yet been eclipsed by the divine right of kings, in which egalitarian values of social solidarity had not yet been suppressed by the rampant inequalities generated by capitalist class warfare and racist imperial science.

Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid rekindles this critique, grounding a vision of what it means to be human in the social commons and practices of commoning. The links he laid out between cooperation in nature and solidarity among the multitude were incendiary and remain so. His insistence on the persistence of the human instinct for solidarity, of mutual aid as the foundation of morality, could not be more important as humanity collectively confronts the struggle against a capitalist system bent on planetary ecocide. Kropotkin’s arguments for mutual aid offer inspiration for a vision of scientific inquiry and political struggle for the common good rather than for profit. His work reminds us that there are alternatives to capitalist competition, plunder, and feckless, ceaseless growth. It is a vision of a world without inequality and without the cops and jails and racism that maintain and intensify such inequality.

A complementary vision can be found in the work of the many Indigenous activists who have fought to preserve and elaborate traditions of care for kin and planet. Today these struggles for alternative futures are articulated in the work of contemporary activists such as the Red Nation, whose Red Deal lays out a series of key signposts for radical climate action, proposals that call for action beyond the scope of the US colonial state. For the Red Nation, decolonization must be paired with the total cessation of carbon extraction and emissions that climate scientists are calling for. It is from these interwoven practices of decolonial work and radical scientific inquiry that a red natural history adequate to the task of ending planetary ecocide will blossom.

Ashley Dawson is professor of postcolonial studies in the English department at the Graduate Center, City University of New York and the College of Staten Island. His latest books include >em>People’s Power: Reclaiming the Energy Commons (O/R, 2020), Extreme Cities: The Peril and Promise of Urban Life in the Age of Climate Change (Verso, 2017), and Extinction: A Radical History (O/R, 2016). A member of the Social Text Collective and the founder of the CUNY Climate Action Lab, he is a long-time climate justice activist.